In the first three parts of this series, we looked at the origins of the Treaty of 1854 and closely examined six days of negotiation. We summarized the agendas and needs of the Miami Nation, Myaamiaki living in Indiana, and the U.S. government (Part 1, Part 2, & Part 3) . Over these six days, we observed that all the attendees recognized multiple times that treaty power sat with the Miami Nation in Waapankiaakamionki west of the Mississippi. Everyone agreed that the Myaamiaki in Indiana could offer their opinions of the treaty, but all final decisions rested with the government of the Miami Nation. We also saw how pain over the 1846 forced removal, the mispayment of annuities, the stress over the ending of a $25,000 annuity, the interference of outsiders, and the constant pressure to sell land led to disagreement and conflict between the Miami Nation and the Myaamiaki living in Indiana. In part four, we will look at how the negotiations of the Treaty of 1854 were concluded.

Day 7 – June 1, 1854

The seventh day of negotiation began in the early evening at 8:00pm with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, George W. Manypenny, reading a draft of the treaty. After the reading finished, Representative Andrew Jackson Harlan of Indiana opened the discussion by asking about “any Miamies who may go from Indiana west getting a part of the reserved land.” Representing the Miami Nation, Akima Neewilenkwanka responded by stating that the reading of the treaty is correct. More detail isn’t provided in the transcript, but what appears to be understood is that the elected leaders of the Miami Nation could select reserves to be given to Myaamia people living in Indiana who agree to move into the nation’s lands in Waapankiaakamionki. Harlan replied that the Myaamia from Indiana had “no interest in any other benefits of the treaty” and that “they do not know of any who will go west now.”

Manypenny then turned to explaining the treaty articles that dealt with the $25,000 annuity and promised goods and services and once again asked about his interest in buying some part of the Mihšiinkweemiša Reserve. Once again, Harlan injected himself into the conversation to state that he thought Mihšiinkweemiša would agree to sell six or seven sections of land from his family’s reserve, but when asked directly by the commissioner if this was true, Mihšiinkweemiša remained silent. Silence was an important negotiating strategy used by Myaamiaki to avoid agreeing to things that they disliked while also avoiding direct verbal conflict, which was understood in some cases to be insulting. It is perfectly clear in the treaty transcript that Mihšiinkweemiša did not want to sell his family’s land and had likely grown exasperated with Manypenny’s continual promptings to consider a sale.

Following the period of silent resistance by Mihšiinkweemiša, the meeting quickly devolved as Neewilenkwanka took control and used his time to state that more time was needed to think about the value of their land and that his nation was still upset with how annuities were handled after the 1846 removal. It seems as though Neewilenkwanka recognized that if Manypenny was going to keep repeating his aggressive attempts to secure Myaamia land and reduce U.S. government payments, then he was going to use every opportunity to point out how he and his nation had been mistreated. Perhaps throwing the commissioner a bit of a bone at the end of a contentious day, Neewilenkwanka told Manypenny that he would be willing to leave the matter of the division of the annuity of tobacco, salt, iron, and steel for the U.S. government to decide.[1]

Day 8 – June 2, 1854

The commissioner opened this day’s meeting by stating that he has made up his mind about how to handle the issues of the division of the tobacco, salt, iron, and steel. He followed by asking if there were any other matters for them to discuss. There must have been a certain level of irritation in Manypenny’s opening statement as Neewilenkwanka responded that he was “not to blame for this business being so long… it is because white men have intermeddled” and “cannot get along so well.” The Myaamia families from Indiana are not recorded as speaking during this day’s meeting, but this passage makes it fairly clear that from the Miami Nation’s perspective the root cause of the intra-Myaamia friction were disagreements between Commissioner Manypenny and Representative Harlan. There was only so much that Myaamia people could do to protect themselves in the 1850s, but they understood that the U.S. government was pitting them against each other.[2]

Akima Neewilenkwanka moved on to discussing the price per acre that would be paid for their lands and handed the commissioner a paper with his nation’s position. Manypenny read their statement but replied negatively that the U.S. could not agree with the submitted terms. He then accused the Miami Nation of “being influenced by white men”and lamented, “he had done the best he could for them.” Despite Manypenny’s assertion of his benevolence, the leaders of the Miami Nation seem to have understood that no one had their best interests at heart except for themselves.

At another critical moment in the discussion, Neewilenkwanka avoided using Lenipinšia “Baptiste Peoria” as his translator. Instead, he spoke through Šoowilencišia “John Bowrie” to voice his disagreement with the process of public land sales and lay out how he would like the funds from this treaty distributed. They then discussed funds for the back payments due to the Eel River village Myaamiaki and adjourned the meeting.[3]

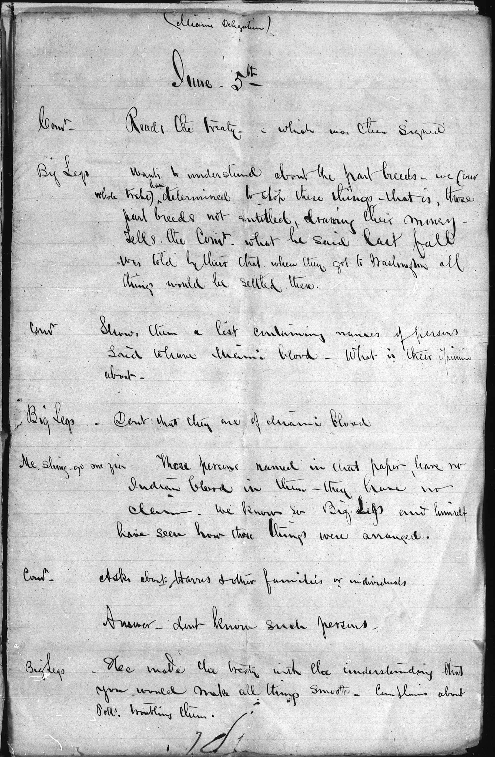

Day 9 – June 5, 1854

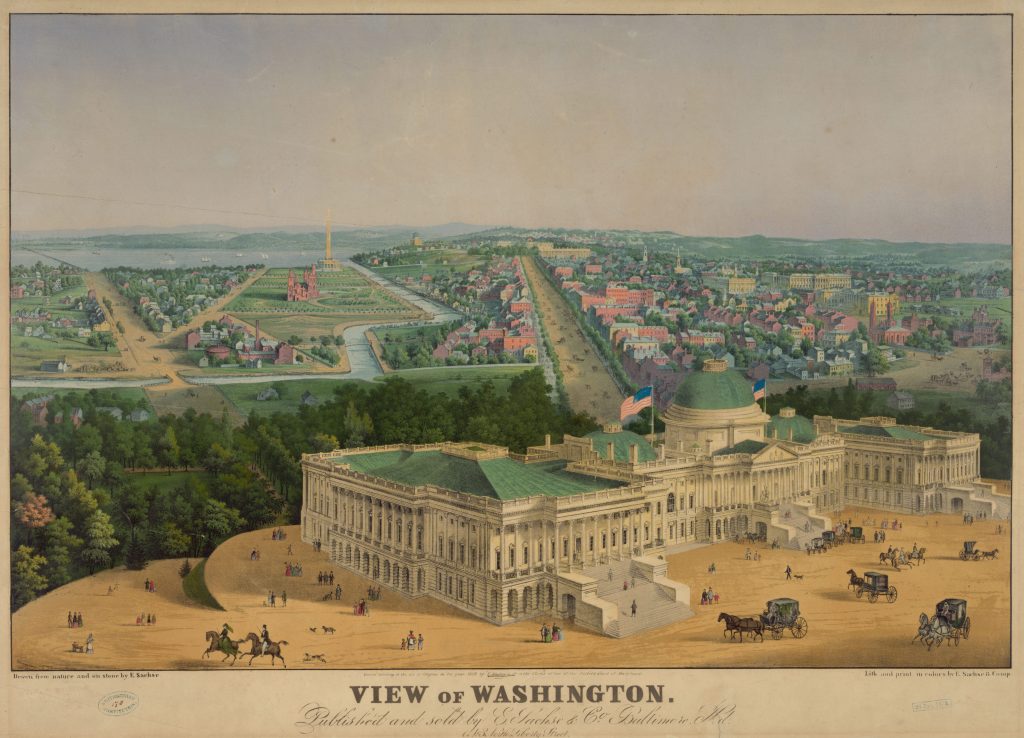

This the ninth day of negotiation opened with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs reading the preamble of the 1854 Treaty of Washington.[4] The treaty text began with the following preamble:

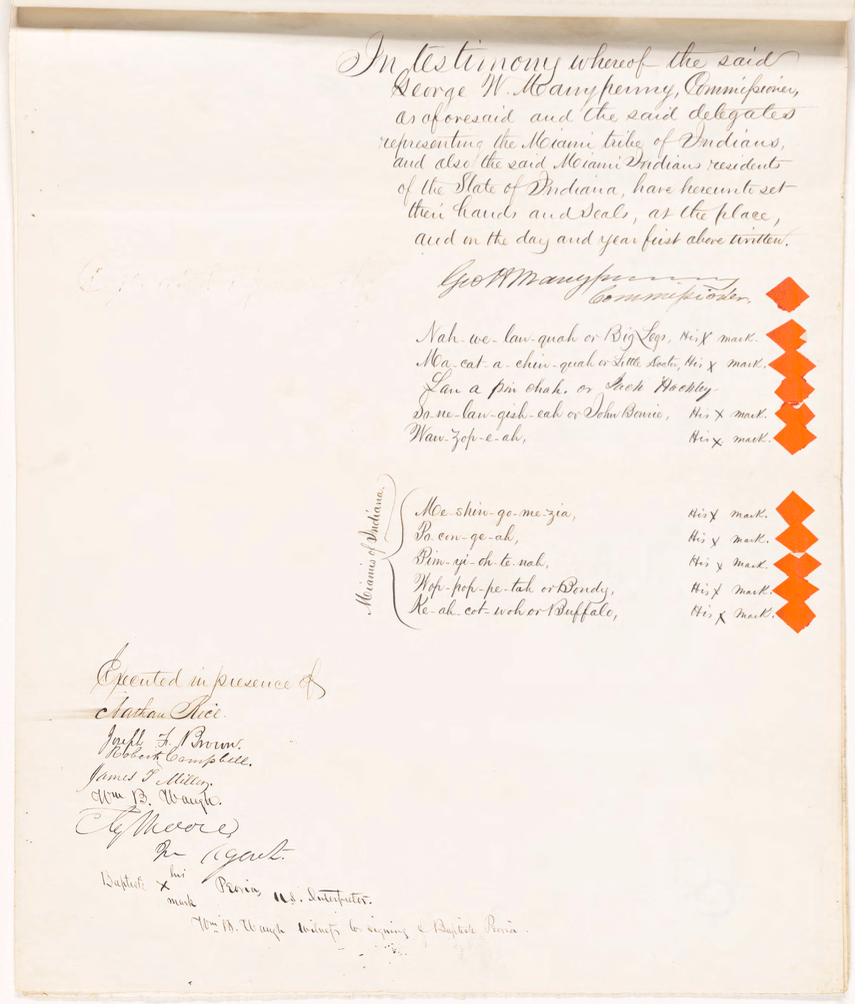

Articles of agreement and convention made and concluded at the city of Washington, this fifth day of June, one thousand eight hundred and fifty-four, between George W. Manypenny, commissioner on the part of the United States, and the following-named delegates representing the Miami tribe of Indians, viz: Nah-we-lan-quah, or Big Legs; Ma-cat-a-chin-quah, or Little Doctor; Lan-a-pin-cha, or Jack Hackley; So-ne-lan-gish-eah, or John Bowrie; and Wan-zop-e-ah; they being thereto duly authorized by said tribe—and Me-shin-go-me-zia, Po-con-ge-ah, Pim-yi-oh-te-mah, Wop-pop-pe-tah, or Bondy, and Ke-ah-cot-woh, or Buffalo, Miami Indians, residents of the State of Indiana, being present, and assenting, approving, agreeing to, and confirming said articles of agreement and convention.

Likely after a dramatic pause, Manypenny then went on to read the fourteen articles of the treaty, and participants gathered to sign it with no apparent discussion.

We do not know the order of who signed on June 5, but at the top of the treaty sits the signature of George W. Manypenny. The commissioner’s signature is then followed by four marks and one signature of the delegated leaders of the Miami Nation: Akima Neewilenkwanka, Mahkateeciinkwia “Little Doctor,” Lenipinšia “Jack Hackley,” Soowilencihsia “John Bourie,” and Awansaapia. Of these five men, only Lenipinšia “Jack Hackley” signed his full name. The rest made marks that look like x’s to indicate their agreement. It is possible that of these five leaders only Lenipinšia was literate and capable of signing his name. However, since the 1800s, literate Myaamia leaders often chose to sign with x marks and thereby not set themselves apart from their relatives who could not write.

The original treaty document included a separate space for the “Miamis of Indiana” to sign and here we see the marks of Mihšiinkweemiša, Pakankia, Pimweeyotamwa, Waapapita “Peter Bondy,” and Keahcotwoh*. Nowhere in the entire text of the Treaty of 1854 is it indicated that the U.S. government treated these five men as representing a separate sovereign nation. The analysis of the treaty transcript over these four posts demonstrates that the Commissioner of Indian Affairs did not believe that these five men had to agree for the treaty to move towards ratification. Manypenny did mention multiple times that he hoped the Myaamiaki from Indiana would agree, and their marks indicate that he got what he wanted. Harlan was not a U.S. Senator, but Manypenny may have still worried that the Representative from Indiana could disrupt the ratification process if Mihšiinkweemiša, Pakankia, Pimweeyotamwa, Waapapita “Peter Bondy,” and Keahcotwoh* did not agree to the changes in the annuity in which they had ongoing rights to treaty payments established by treaty and legislation.

The last to sign the treaty were the witnesses and official translator: Nathan Rice, Joseph F. Brown, Robert Campbell, James T. Miller (who traveled with the Myaamiaki from Indiana), William B. Waugh, Ely Moore (Indian agent from the Miami Nation’s agency), and Lenipinšia “Baptiste Peoria” (official U. S. interpreter for the treaty). Lenipinšia made a mark looking like a small x and Waugh witnessed his mark.[5]

After everyone signed the treaty, Neewilenkwanka asked again about people unaffiliated with the Miami Nation or the Myaamia families in Indiana who were receiving annuities. The commissioner showed a list of these families and both Neewilenkwanka and Mihšiinkweemiša vociferously denied that those on the list were Myaamia. Akima Neewilenkwanka went on to restate that they “made the treaty with the understanding you would make all things smooth.” With no explanation, Neewilenkwanka stated that he was also troubled by claims that the Potawatomi were making. The transcript does not provide any additional information about these claims.[6] Apparently, Manypenny did not respond to either of these points, but the leaders of the Miami Nation had every reason to believe that those not recognized would no longer receive a part of their annuity payments.

The men then moved on to discussing the fine point details of the division of annuity money and the conversion of promised resources into cash equivalents. Neewilenkwanka recognized that after nine days of negotiations the discussions had been drawn out longer than anyone anticipated, yet he had a few more important issues to address with the commissioner. He pushed the Manypenny to discuss the specifics of funding a school on the Miami Nation’s lands in Waapankiaakamionki and that it would be supported out of the promised treaty payments. Neewilenkwanka closed out the day by requesting more information about the money owed to Myaamia orphans and asked that David Lykins be placed in charge of the proposed school.[7]

Day 10 – June 7, 1854

Two days after the treaty was officially signed, the Miami Nation delegates met one last time with Commissioner Manypenny. On this day, they were joined by their relatives from the Confederated Peoria, Kaskaskia, Wea, and Piankashaw Nation who were in Meetaathsoopionki to negotiate their own treaty. This was likely the last meeting the representatives of the Miami Nation had with Manypenny before returning to Waapankiaakamionki.

Manypenny opened this day by giving his ruling on the families that the Miami Nation said should not receive annuities. Manypenny acknowledged “that they should not be enrolled and regarded as Miamis without the consent of the chiefs—but if it should be proven to him that some are excluded who are entitled to draw annuities” the nation’s “decision will not be binding.” Neewilenkwanka replied that he still did not recognize these people as members of his community. However, he agreed that the nation would reimburse them for any losses they incurred when they were forced to remove themselves from the reserve boundaries. This final discussion is representative of the grabbing of bureaucratic power by the Office of Indian Affairs under Manypenny’s leadership. His respect for tribal nations’ inherent right to decide who belonged to their nations only went so far. He reserved the right to overrule an elected tribal government’s decision if he came to the determination that they were wrong.[8]

In part four of this series, we looked at how the treaty negotiations were brought to a close after a long and at times trying series of discussions and arguments. In our fifth and final post of this series examining the Treaty of 1854, we’ll explore the impacts and implications of this agreement for Myaamia people.

Notes

[1] Treaty of 1854, “Miami Conference May 30, 1854.” Ratified treaty no. 274. Documents relating to the negotiation of the treaty of June 5, 1854, with the Miami Indians (available digitally at https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AAKQKRUJZNAQM39A).

[2] Treaty of 1854, “May 30.”

[3] Bert Anson, The Miami Indians, 1st ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 239-40.

[4] “Father” is a metaphoric addressing term that Myaamia people and others used to refer to the French King, the British King, and eventually the President of the United States and his delegates. Originally this was a term used with a specific set of Myaamia cultural expectations: fathers were to show only love to their children and provide them with what they needed to be well-fed and well-sheltered. However, Myaamiaki and other Indigenous peoples had long since given up on these expectations when dealing with Europeans and Euro-Americans. By that point the practice of using this term was ingrained in the political culture of the Miami Nation.

[5] Treaty of 1854, “May 31.”

[6] Treaty of 1854, “May 31.”

[7] Six years after this treaty, the Miami Nation would officially petition to have Lenipinšia removed as their interpreter and have Waapimaankwa “Thomas Richardville” installed in his place. Minutes of the Miami Nation Council from October 29, 1860, Miami Nation Council Book 1, Myaamia Heritage Museum and Archive, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami, Oklahoma; ibid Minutes of the Miami Nation Council from November 12, 1860.

[8] Treaty of 1854, “May 31.”

Leave a comment