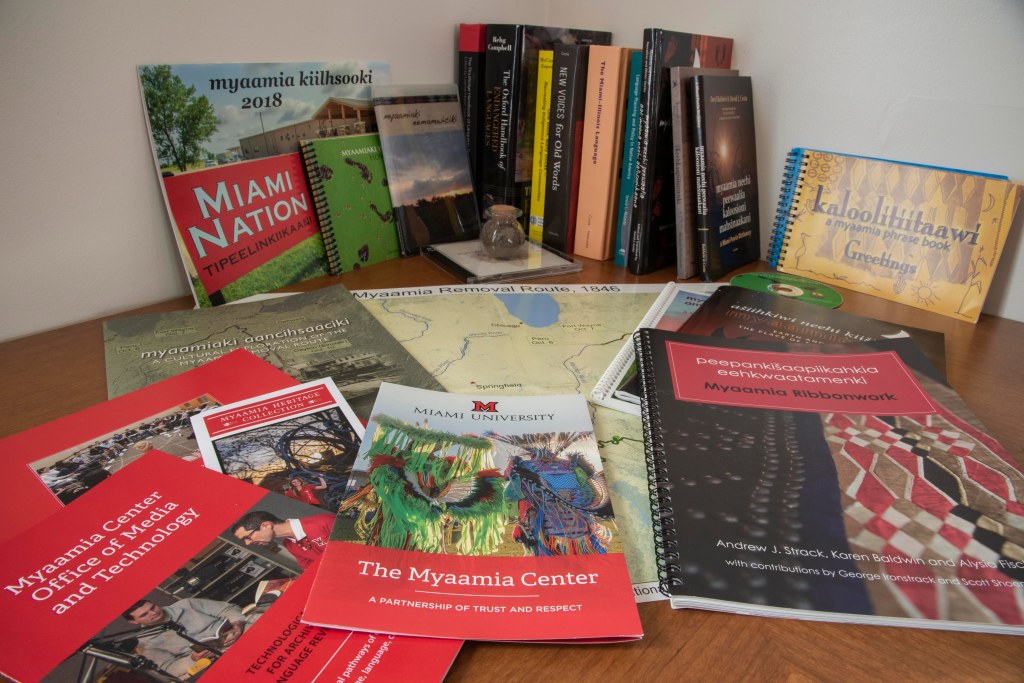

Over the summer, the Office of Language Research at the Myaamia Center reached 100,000 entries in the Miami Tribe’s Indigenous Language Digital Archive, commonly known as the ILDA database that feeds the Myaamia dictionary.

The Office of Language Research is a multi-person team with two linguists; Dr. David Costa and Dr. Hunter Thompson Lockwood; and a transcriptionist, Carole Katz. This team regularly collaborates with Michael McCafferty from Indiana University, who performs translation work.

These individuals are doing the meticulous work of locating, transcribing, and analyzing archival language documents to be added to the ILDA database, where the Myaamia community can easily access the language. This 100,000 milestone is a testament to over 30 years of research that ultimately led to the revitalization of Myaamiaataweenki ‘the Myaamia language.’

However, the team didn’t always look like this. Over those 30 years, countless people have contributed to this work by sharing knowledge, time, and resources. One of the people on this team has been working with Myaamiaataweenki long before the creation of the Myaamia Center at Miami University.

This is the first post in a series on Aacimotaatiiyankwi about the role of language in Myaamiaki Eemamwiciki ‘the Miami Awakening’, and the people whose work has made the awakening possible.

Dr. David Costa is known in the linguistics community as an Algonquian language expert. He’s been studying Myaamiaataweenki since the late 1980s while pursuing a Ph.D in linguistics from the University of California, Berkeley. He’s worked directly with the Miami Tribe for over 20 years and has formally been the Director of the Office of Language Research at the Myaamia Center since 2017.

David isn’t Myaamia or Native American and didn’t grow up in the Myaamia homelands. So, how did he become an invaluable member of the Myaamia community and contribute to changing the course of history for our tribal nation?

During his Ph.D research, while coauthoring a paper on Algonquian languages with his advisor, he was tasked to “see what he could find on the Miami language”. David found a sizeable collection of materials in the archive and became intrigued by this Indigenous language that had yet to be analyzed by linguists.

He remembers asking his professor if there was enough content for a dissertation, with no idea he would come to acquire enough archival material for a lifetime of analysis.

As was common in his field, he sought to find speakers of the Miami language; first in Oklahoma and then in Indiana. While some elders in these communities had word lists, remembered names in the language, or had memories of it being spoken, he found that the community had set the threads of language down. Nobody was speaking Myaamiaataweenki. Instead, he found stories from those elders, bits of knowledge about Myaamia culture and life in the early-to-mid 1900s.

“While it had nothing to do with language,” David said. “I realized for the first time that I might be collecting something else of value.”

On one of these trips, he met Daryl Baldwin, a member of the Miami Tribe, at a powwow. Daryl, now executive director of the Myaamia Center, had just completed his master’s degree in linguistics and was looking to learn more about his community’s language. This first introduction was short, but the beginning of a long working relationship.

When David talks about the early days of his linguistic studies, he mentions a temp job as a file clerk at Clorox in Oakland, California almost as an afterthought; but this was his full-time “day job” and main income source during the last few years of his dissertation research. He would even save vacation days with the company to make those trips to Oklahoma and Indiana.

Finally, in 1994 after countless visits to archives, libraries, and museums to collect dictionaries and written documentation of the Myaamia language, his dissertation was filed and David now held his Ph.D in linguistics.

David’s research process, linguistic analysis from archival documentation, wasn’t common in linguistics, and most of his peers didn’t see the value in it. They couldn’t understand why he would study a language with no speakers, but for David, it just added to the complexity of the puzzle he was trying to solve.

“Maybe the Miamis would be interested in this,” he thought. So, he arranged to have a copy of the dissertation sent to Daryl Baldwin, who was both surprised and excited to see so much available information on the language.

The two began conversing regularly and in the late 1990’s, David was introduced to Julie Olds at the Miami Tribe’s Cultural Resource Office. This introduction allowed him to start formally working with the Miami Tribe through contracted projects, mostly providing language information for in-home learning materials.

In 2000, David was able to quit his “temp” job after eight years with the company and start working with Algonquian tribes on a full-time basis. Just one year later, the Myaamia Project (now the Myaamia Center) was established at Miami University with the goal of studying Myaamiaataweenki to integrate it back into the Myaamia community. While Daryl Baldwin was the only employee at the Myaamia Project for a few years, the Miami Tribe understood he needed support, so they continued hiring David to do research for the project.

When the Myaamia Project formally transitioned to the more permanent Myaamia Center in 2013, Daryl knew it was time to bring David to the Myaamia Center as a full-time employee.

David discussed the decision at length with Mary, his wife, and their teenage child. Mary was established in her teaching career and their child was only going to be living at home for a few more years, so a cross-country move didn’t make sense for the family.

The next year, Daryl found a way for David to join the staff remotely from California. After working with the Myaamiaataweenki for over 20 years, this research had finally become his full-time job, one with pension and benefits. Daryl and David agreed that when Mary retired from her teaching position, they would move across the country from California to Oxford, Ohio, a small college town just north of Cincinnati.

It wasn’t an easy decision, especially when David’s child, a young adult at the time, had decided she wasn’t moving with them. Regardless, in the summer of 2017, David and Mary packed their belongings and moved to Oxford.

Today, the couple still feels they made the right decision. Mary, an author and writer, spends her retirement working on her novels and pursuing an MFA at Miami University, while David still works full-time leading language research for the Miami Tribe at the Myaamia Center. While they both miss their daughter, they make trips to see her multiple times per year and she visits them in Ohio, too.

The field of language revitalization from archival documentation is becoming increasingly common and David’s research has allowed the Miami Tribe to provide guidance and assistance to other tribal nations now interested in engaging in this work themselves.

While nobody, including David, doubts that the Myaamia community would have eventually found the archival documentation, he found it at a time when nobody was looking for it or even knew it existed. He began compiling and analyzing it, saving the community years of research when we were ready to pick up the threads of language again.

In future posts in this series, we will explore the process of language revitalization from documentation and learn how this research is used by the Myaamia community.

Leave a comment