In the first four parts of this series, we looked at the origins of the Treaty of 1854 and closely examined ten days of negotiation. We summarized the agendas and needs of the Miami Nation, Myaamiaki living in Indiana, and the U.S. government (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, & Part 4). Over these ten days, we observed that all the attendees recognized multiple times that treaty power sat with the Miami Nation in Waapankiaakamionki west of the Mississippi. Everyone agreed that the Myaamiaki in Indiana could offer their opinions of the treaty, but all final decisions rested with the government of the Miami Nation. We also saw how pain over the 1846 forced removal, the mispayment of annuities, the stress over the ending of a $25,000 annuity, the interference of outsiders, and the constant pressure to sell land led to disagreement and conflict between the Miami Nation and the Myaamiaki living in Indiana. In part five, we will look at the impacts of the Treaty of 1854 on the Miami Nation and its people.

The treaty negotiated in May and June of 1854 had a massive impact on the Miami Nation. It reduced the collective lands of the nation by about 80% from around 325,000 acres to 70,000 acres.[1] It also laid out the mechanisms for how the remaining 70,000 acres would be divided up into individually held parcels of 200 acres each. The Miami Nation planned to continue to hold a part of the land in common for the benefit of future generations, but the intent on the part of the U.S. government was to gradually erode the strength of the nation. Through land loss, they sought to push the tribe into such a weakened state that it would one day cease to exist.

Following the treaty, the elected leaders of the Miami Nation believed they retained the right to decide who was a part of the nation and would receive a part of the national landbase. This allowed the nation to make population decisions based on recognized familial connections. They could be flexible when it suited the good of the nation. For example, Myaamiaki living in Indiana who were recognized as a legitimate part of the community were allowed to relocate to Waapankiaakamionki and receive land within the Miami Nation. The 1854 treaty record demonstrates that Myaamiaki, no matter where they lived, maintained a strong sense of kinship and community. The record of the discussions and debates in the early summer of 1854 shows us how Myaamiaki were at their strongest when they worked together. Removal had divided Myaamia people geographically, but this treaty demonstrates how the Miami Nation, though based west of the Mississippi, was strongest when all Myaamiaki worked together through that singular governmental structure to secure a Myaamia future.

This treaty also spells out how the Miami Nation and the U.S. government perceived Myaamia families living in Indiana. The treaty preamble referred to these families as “residents of the state of Indiana” and article three of the treaty refers to them as “persons, families, or bands” who by specific treaties and legislation were “permitted to draw or have drawn, in the State of Indiana, their proportion of the annuities of the Miami tribe.”[2] Following this treaty, “Indiana Miami” became a shorthand for referencing residency for the purposes of payments. Myaamia living in Indiana at the time of this treaty received different annuity payments from those living within the nation. This different payment status endured even if an individual moved into the nation in Waapankiaakamionki. Neither the treaty text nor the accompanying transcript refer to the Myaamia living in Indiana as a tribal nation. Mihšiinkweemiša, Pakankia, Pimweeyotamwa, Waapapita “Peter Bondy,” and Keahcotwoh* did not present themselves as representing the government of a tribal nation located in Indiana. In fact, Mihšiinkweemiša made it clear that he attended the treaty negotiation to look after “his women and young men & children, now growing up” (see Part 3 in this series for more on this point).[3] They wanted to protect their inherited rights to the $25,000 annuity. None of these men disputed the assertion that the Miami Nation was located west of the Mississippi in Waapankiaakamionki “Marais des Cygnes River Valley.”

The disputes that did emerge during the course of the treaty negotiation make it clear there certainly was, at times, strong disagreement between Myaamia people living in the Miami Nation and those living in Indiana. Those who endured removal, like Neewilenkwanka, were scarred by the experience and eight years later still felt grossly wronged. Neewilenkwanka believed that too many Myaamiaki had been allowed to return to Indiana and that a greater portion of the nation’s resources were going there instead of to the nation’s new home in Waapankiaakamionki. He also resented that many non-Myaamia people were receiving annuities, and because of a lack of communication with his relatives in Indiana, he assumed that the source of the problem sat there.

The issue of ending the $25,000 perpetual annuity caused the most controversy between the two groups of Myaamiaki who were gathered together in Meetaathsoopionki. In the years that followed, the controversy would only continue as many Myaamiaki felt that Manypenny had unethically, and perhaps illegally, pressured the Miami Nation into accepting the ending of this annuity.[4]

In July of 1854, Myaamia families living in Indiana sent a letter to Commissioner Manypenny officially protesting the termination of the $25,000 perpetual annuity. In the letter, they describe themselves as “that part of the Miami Tribe Indians who live in the State of Indiana.” They argued that the perpetual annuity had been created through the work of “the wisest chiefs the Tribe ever had, by men who could look into the future” and see their coming struggles. This annuity, they pleaded, was designed to protect future generations “until their Tribe was no more.” They believed that this important source of community support was being relinquished because the leadership of the Miami Nation was being manipulated by Lenipinšia “Baptiste Peoria.” The letter does not spell out the specific reasons why they believed Lenipinšia was acting in such a manner, but evidence from other sources indicates that Myaamia people feared that he was interested in merging the Miami and Peoria tribes together under his leadership. Near the conclusion of the letter they pleaded with Manypenny to “[b]e just” and “preserve in this annuity, that monument of wisdom of our fathers, that shield to protect the poor old men from the Beasts of oppression & wrong.”[5]

At no point in this letter did the signers claim to be a separate Myaamia government. There is no mention of elections or established leadership positions among the Myaamia living in Indiana. Instead, we find clear evidence that those who wanted to serve in Myaamia government moved to the nation’s reserve west of the Mississippi. Two of the signatories of the July 1854 letter went on to serve in the Miami Nation government in Waapankiaakamionki. Waapeehsipana “Louis Lafontaine” signed the 1854 letter and six years later was unanimously elected to the Miami Nation council in a council meeting hosted in his house on the nation’s reserve west of the Mississippi.[6] Waapimaankwa “Thomas Richardville” also signed this 1854 letter and later was elected to the positions of interpreter, clerk, secretary, council person, second chief, and chief within the Miami Nation.[7] While the Myaamiaki living in Indiana were not a government, the July 1854 letter demonstrates that they understood their inherited treaty rights and sought to protect those rights and advocate for their families to the best of their abilities.

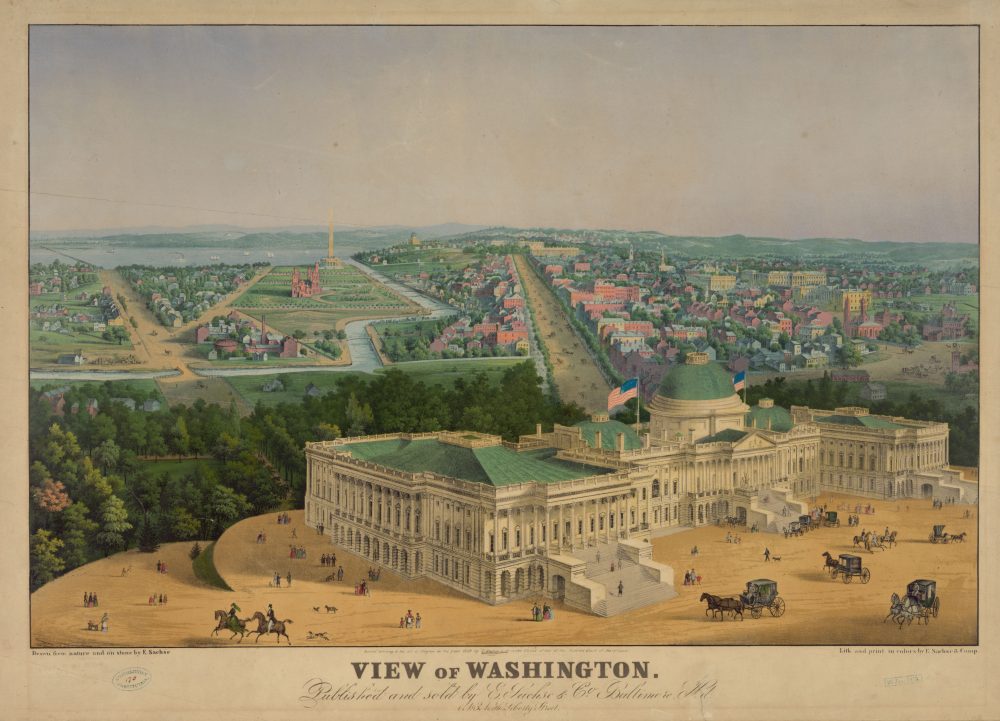

The families who signed the July letter sent representatives to Meetaathsoopionki ‘Washington, D.C.’ to officially request that the Senate make an amendment to the 1854 treaty. On August 4, 1854, the Senate amended Article 4 to reflect the Indiana family’s wishes that the U.S. government invest their part of the lump sum created by the ending of the permanent annuity. Interest from that investment would then be paid to the families for twenty-five years. After twenty-five years, or sooner if they requested it, the lump sum would be paid out to these same families. The amendment also spelled out that only the families allowed to remain in Indiana by treaty or legislation would be allowed to determine who was legitimately able to receive these payments. In the notes from the ratification session, the senate secretary noted that these changes would not need to be approved by the Miami Nation because they did not affect payments made west of the Mississippi.[8] At no point in this amendment process did either the U.S. government or Myaamia people themselves refer to the Myaamia living in Indiana as having a separate organized Myaamia government.

In the period of treaty-making prior to forced removal, these amendments would have been sent back to the Miami Nation for approval. However, during the 1850s both the federal bureaucracy (Office of Indian Affairs) and the U.S. Congress began to disregard and ignore aspects of tribal sovereignty in the service of more quickly completing the transfer of land from tribes to the United States. The hoped-for end goal of this more “efficient” process was the eventual “abolition” of tribes as distinct political and cultural nations (see Part 1 in this series for more on this policy shift). The endurance of the Miami Nation stands as a testament to the strength of Myaamia resistance through this difficult period.

The 1854 Treaty of Washington was the second to last fully ratified treaty that the Miami Nation negotiated with the United States. Following the challenging times of Bleeding Kansas and the U.S. Civil War, the Miami Nation struggled even more to create the kind of political unity that made them such strong negotiators prior to the 1840s. In the 1860s and 1870s, squatters and resource thieves plagued the Miami Nation’s lands, and political factions within the nation seeded discord and distrust among the interrelated Myaamia families. The Treaty of 1854 created many of the chaotic circumstances around land ownership that facilitated the squatting and theft that engulfed the nation. Following the end of the U.S. Civil War, the Office of Indian Affairs would take up the position that the state of Kansas was not a fit home for the Miami Nation, and once again, they should move. The last ratified treaty that the Miami Nation negotiated with the U.S., the 1867 Treaty of Washington, paved the way for the second forced removal south to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Treaty-making came to an end for all tribal nations as a result of infighting between the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, but the Miami Nation endured. The nation continued to organize itself and care for its people on the shared Miami-Peoria Reservation in Indian Territory, and they continued this difficult work on the little reservation land they had left following the birth of the state of Oklahoma.

Today, the Miami Nation has rebuilt itself on its reservation lands in what is today Oklahoma. The elected government of the nation and the people it employs work together to serve the needs of all citizens of the nation no matter where they live. The nation once again governs trust lands in what is today the state of Indiana and cares for its citizens who live in that state today.

In many ways, the Treaty of 1854 was an inflection point in the history of the Miami Nation. The treaty set in motion a series of external forces that would stress the nation nearly to its limits. However, the treaty also reminds Myaamia people of our greatest strengths. In the midst of divisive circumstances created by the U.S. government, Neewilenkwanka and Mihšiinkweemiša were able to come together as kin and try to find the best path forward for all their Myaamia relations.

Notes

[1] The area of the reserve was supposed to be 500,000 acres. The Miami Nation and the U.S. government attempted to address this monumental error later through the Indian Claims Commission. Bert Anson, The Miami Indians, 1st ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 241.

[2] Ratified Indian Treaty 274: Miami – Washington, DC, June 5, 1854. See treaty article 3. https://digitreaties.org/treaties/treaty/169692034/ For a typed transcript of this treaty see https://treaties.okstate.edu/treaties/treaty-with-the-miami-1854-0641

[3] Treaty of 1854, “May 31.” Treaty of 1854, “Miami Conference May 30, 1854.” Ratified treaty no. 274. Documents relating to the negotiation of the treaty of June 5, 1854, with the Miami Indians (available digitally at https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AAKQKRUJZNAQM39A).

[4] See letter dated July 20, 1854. M234 – Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1881. Roll 644, 977. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/164254043?objectPage=977. In the 20th century, the Indian Claims Commission would later rule that this annuity had been terminated against the wishes of the Miami Nation. The ruling referenced Neewilenkwanka’s statement that he wished the annuity to continue forever. Anson, Miami Indians, 241.

[5] July, 1854 Letter.

[6] Minutes of the Miami Nation Council from October 29, 1860, Miami Nation Council Book 1, Myaamia Heritage Museum and Archive, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami, Oklahoma.

[7] Miami Nation Council Book 1, Council Meetings July 23, 1870; February 17, 1885; December 10, 1887; and December 11, 1888.

[8] Documents related to the ratification of the Treaty of 1854, 9-10. Neewe ‘thank you’ to Cameron Shriver for his help researching the complicated story of overlapping responses to the ratification of the Treaty of 1854.

Leave a comment