Written by: George Ironstrack and Nate Poyfair

Background for the trip

For more than thirty years, Myaamia artists and historians have been studying images of four minohsayaki ‘painted hide robes’ held in the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac collections in Paris, France. These robes were produced by ancestors of our Peewaalia ‘Peoria’ relatives.1 There are deep ties between the Myaamia and Peewaalia that extend back into time immemorial. In the early 1800s, Myaamia leaders referred to the Peewaalia as “their younger brothers.” They understood that the Peewaalia descend from people who incorporated with the Myaamia at some point prior to contact with Europeans in the distant past.

We speak the same language, which throughout time, is described as completely understandable between the two nations. In the early 1800s, Myaamia leaders stated “the Miamies understand perfectly the Kaskaskias, Peorias, Weas & Piankeshaws, because those tribes have all descended from them. And the difference of dialect is scarcely more than between the present Parisian and the Canadian French.”2

Throughout Myaamia and Peewaalia history, there is also a long practice of continual intermarriage. These deep ties of kinship, language, and history mean that Myaamia and Peewaalia ancestors shared much in common, including a similar visual language. These Peewaalia minohsayaki ‘painted hide robes’, which date to the early 1700s, provide us a rare entry point into the artistic designs and processes of our Myaamia ancestors.

In 2020, our long-held interest in these minohsayaki brought us together with our Peewaalia relatives into a project called Reclaiming Stories. We are incredibly lucky, and honored, that our Peewaalia relatives have been open to partnering with us on this learning journey with their minohsayaki. We are also grateful to Professor Robert Morrissey at the University of Illinois for helping to organize this work, and to the Mellon Foundation Humanities without Walls Program at the University of Illinois for funding the Reclaiming Stories Project.

During the course of our work together on Reclaiming Stories we connected with staff of the Musée du quai Branly and learned that by a pure stroke of luck, they were working on a separate project that also included the minohsayaki.

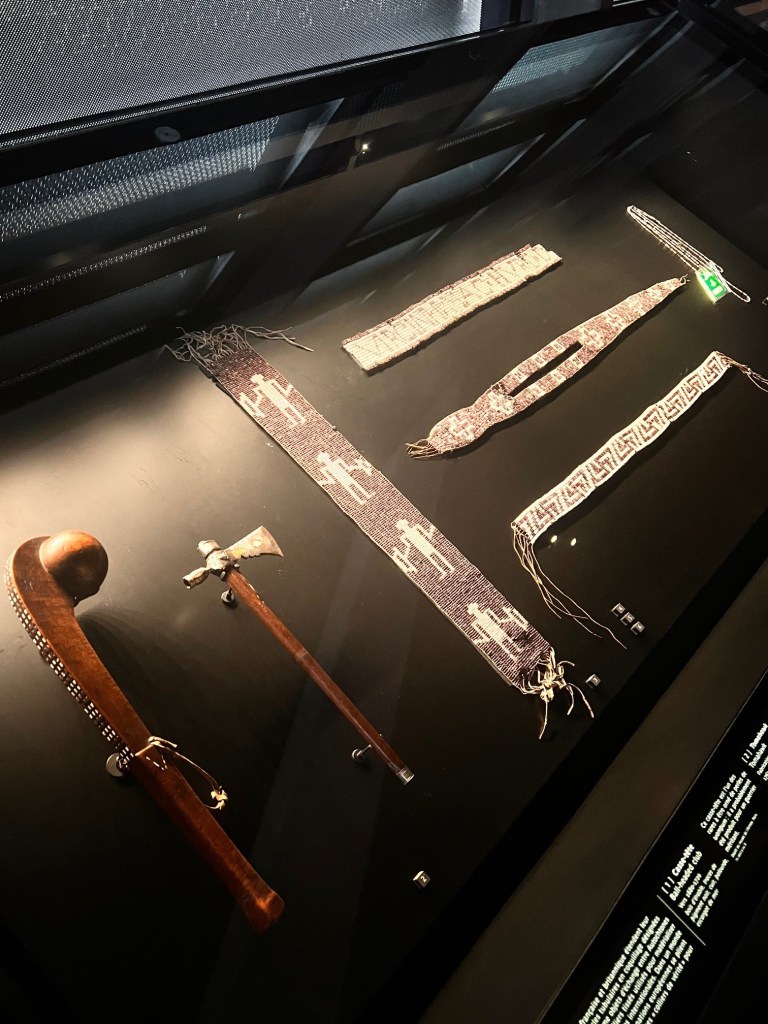

The museum had already partnered with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma on a previous exhibit and was interested in initiating a new project that would also include the Quapaw Nation, the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, and the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. The goals of this new project have emerged from many hours spent together in the museum’s collection spaces looking at objects that came from all of our homelands and passed into the control of the French royal family in the early to mid-1700s. Most of these objects do not have accompanying records that clearly indicate their tribe of origin. However, most of these ancestral objects were produced using tools, techniques, and materials that were shared by many tribes living in the lower Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley. These objects came into French collections through both gift-giving and purchase. A minority of the objects were seized by the French through acts of war.

One important exhibit element that emerged from these visits was the inclusion of a focus on a delegation of tribal leaders from the Peoria (referred to as Illinois at the time), Missouria, Otoe, and Osage Nations who came to France in 1725. These leaders visited many important sites in Paris, including the Palace of Versailles, and spent significant time with the King of France, Louis XV, at his Palace at Fontainebleau.3 It is hoped that a future exhibit will open in France in the Fall of 2025 on the 300th anniversary of this visit.

George Ironstrack and Nate Poyfair, from the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, traveled to Paris this November (2024) to continue studying the ancestral artifacts cared for by the Musée du quai Branly and to visit locations of interest related to the 1725 delegation.

On this trip, they joined their relatives from the Peoria Nation – Charla EchoHawk, director of cultural preservation, and Dr. Elizabeth Ellis, tribal history liaison and professor at Princeton University – and colleague Dr. Robert Morrissey, associate dean for Technology & Online Learning in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

This was George’s third trip to Paris for this project and Nate’s first trip. The itinerary included a private tour of the Palace of Versailles, multiple visits to the Musée du quai Branly to spend time with the ancestral objects in their collections, and a trip to Château de Fontainebleau, which the 1725 delegation visited. This post will focus on our visits with ancestral objects at the museum. A future post will summarize the visits to Versailles and Fontainebleau.

Musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac

The highlight of the visit to the museum was the time spent with the four Peewaalia minohsayaki ‘painted hide robes.’ The entire staff of the Musée du quai Branly was wonderfully welcoming and they facilitated relaxed and easy viewing of these beautiful ancestral objects for large portions of two days. All of the travelers were especially grateful to Dr. Paz Núñez-Regueiro, head curator of the Americas Collections, for playing such a key role as the organizer and facilitator of all of these visits.

The Branly is dedicated to the conservation and documentation of arts from around the world and outside of Europe. The museum holds around 300,000 artifacts from Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Oceania, collected during exploration and French colonialist expansion. These ancestral objects were gifted, purchased, or acquired through colonial conquest. The museum is focused on building “bridges between cultures” and bringing in “varied audiences and inciting curiosity” by creating exhibit spaces that stimulate visitors through the presentation of works from around the world to allow for comparison, provoke thought, and encourage dialogue between cultures and people. The museum, which opened in 2006, was created by architect Jean Nouvel and was built under the orders of then-French President Jacques Chirac to celebrate the arts from around the world.

Minohsayaki neehi Iiši-kiišihenciki minohsayaki ‘Painted hides and how the painted hides were created’

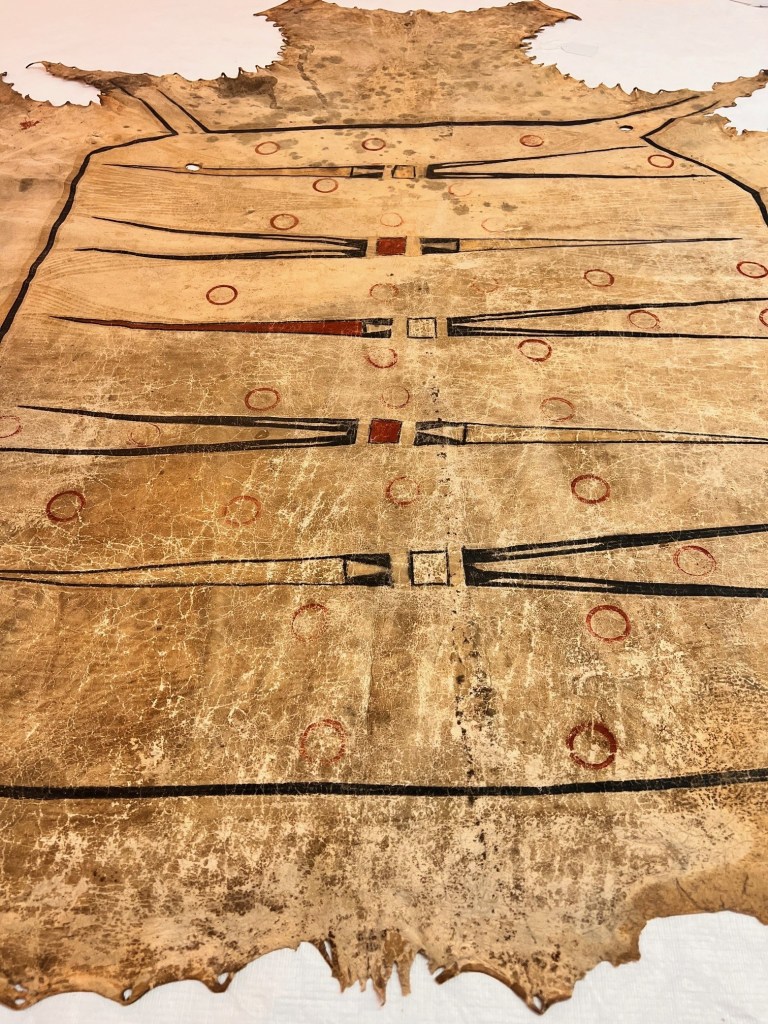

Part of the collection that was observed during our visit to the Branly were four minohsayaki produced by the ancestors of the Peewaalia. These minohsayaki, from the 1700s, are among the best-preserved objects of this type. They have provided us with valuable opportunities to examine up close how Peewaalia people expressed themselves artistically and the methods they used to create these amazing works of art.

Minohsayaki were created through multiple complex stages. The first stage was focused on the hunting of the animals who would provide the hides for eventual painting. The next step involved brain tanning and sometimes smoking the animal hides. Hides were either scraped clean on both sides, or the hair was kept on, while the membrane was scraped from the inside (flesh side of the animal) before tanning.

Moohsooki ‘white-tail deer’ hides were much easier to tan than those of other large mammals such as bison, elk, and moose, due to their relatively thin epidermis and lighter weight. Three of the four hides observed in Paris were moohswayaki ‘deer hides.’

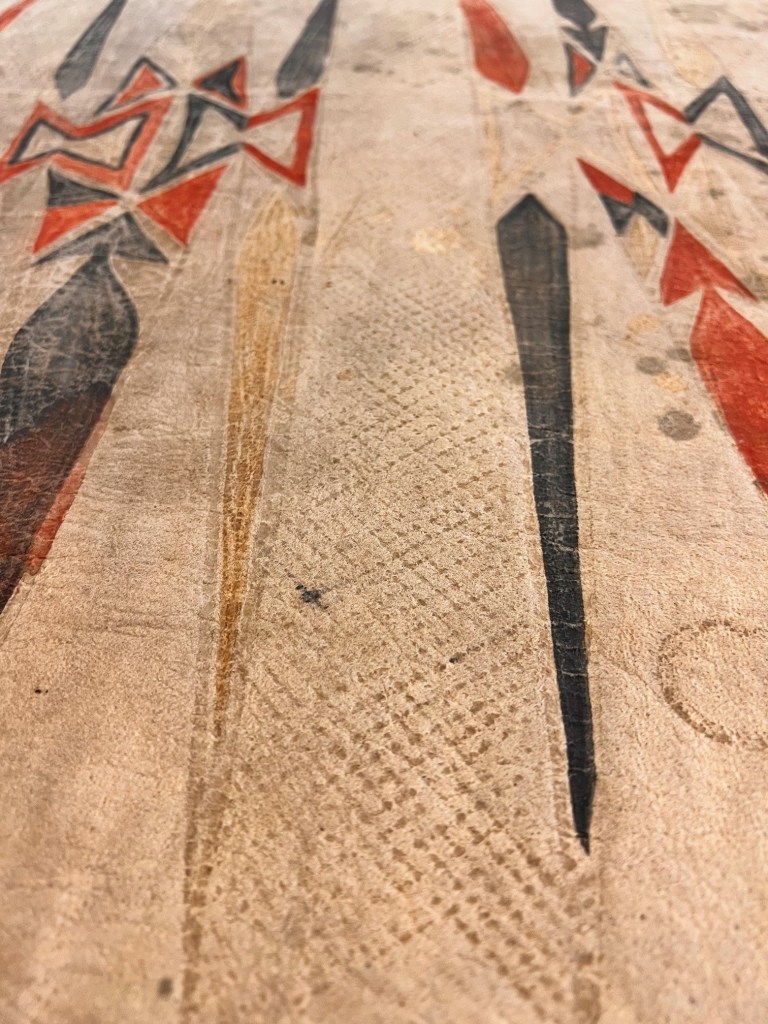

Once tanned and ready for decoration, an artist could have used a variety of tools to create the artistic design of a hide. Wood styluses, fingers and hands, and bone tools were used to paint these hides. All four of the minohsayaki in Paris are filled with beautiful geometric patterns and small circles. In a more limited fashion, some of the minohsayaki include an animal shape, a lodge shape (perhaps), and organically flowing fan shapes. Today, we can only form educated guesses about what these symbols meant to the artists who created them.

Smoking hides was done to preserve and protect the minohsayaki from moisture and bugs. These hides were either lightly smoked or not smoked at all, so we believe these hides were intended to be used ceremonially, as decorations, or as gifts and not intended to be regularly used out in the elements.

Scientifically, smoking hides results in the bonding of the smoke and the collagen fibers, thus preventing fibers from re-connecting. This ensures that moisture does not rot, harden, and impact the overall quality of the hides. Smoking adds permanency to the tanning process and helps preserve them, but smoking does not make them completely waterproof.

No hides had any hair remaining, but there was some remaining epidermis on the undecorated sides. The colors used for each hide were black, red, and yellow. Non-destructive testing has confirmed that the black color was produced by mixing charcoal with a binder (glue-like liquid) and the yellow from an unknown organic source. The red color was produced through trade vermillion and ground hematite, an Indigenous mineral that was likely harvested from Peewaalia homelands. The various patterns were symbols of manetoowaki ‘Other than human beings’, such as ciinkwiaki ‘thunder beings,’ geometric in style, or included other objects such as arrows or calumets. On one hide, in particular, there are also what appear to be four paw prints or footprints within the design as well.

All four hides possessed similar qualities of precise lines and geometric shapes filled with color. The spaces between the colored shapes were often filled with lines painted with clear binder, the glue-like liquid that is used to make paint. These sections decorated with shapes and lines of clear paint likely reflected light and produced an eye-catching shining effect.

The tools used for the painting of the hides were most likely wooden and potentially bone, while there are also evidence signs that fingers or hands were used for filling in larger spaces of color. Many of the hides have perfectly stamped uniform circles on them. What tools were used to stamp these circles has generated a lot of debate. Some researchers outside of this team have hypothesized that the circles were stamped with a gun barrel. The Reclaiming Stories team has hypothesized that the circular stamp could have been made from wood, bone, river cane, or even the spout of a trade glass jug.

Personal Reactions:

George Ironstrack:

What was this trip like?

To answer simply, it was powerful and emotional. The ancestors who produced the objects that we got to visit on this trip created lasting embodiments of their power as human beings. This power was visually evident in the beauty of their art and palpably present in ways that are more difficult to describe using our core senses. Being able to spend extended time in the room with these ancestral objects was also surprisingly emotional. When using our language in song and addressing these ancestral objects, I felt like we were visiting with a grandparent who we had not seen in a long time. I’ve been looking at photos of the four Peewaalia minohsayaki for nearly 30 years, so spending time with them in person will never cease to be a “pinch me!… am I not dreaming?” kind of moment.

This power and emotion leave me with a great sense of obligation and responsibility to my community to work together with the rest of my Myaamia relatives to bring this knowledge home for our people to experience. This experience has also solidified why it is important that we work towards creating an exhibit that can travel to our people’s homeland so that as many of our people as possible can experience what Nate and I experienced on this trip.

To share this experience with Nate, Charla, Liz, and Bob was also impactful. To see their reactions to the power and emotion that we were all feeling magnified the electric-like jolt that I felt when visiting the ancestral objects. I also felt this bond of shared experience as we traveled together to Versailles and Fontainebleau walking in the footsteps of the Peewaalia ‘Peoria’ ancestor, Šikaakwa. As we walked around Paris, rode trains, got meals, and braved the surprisingly cold weather we added another layer to the stories of Indigenous people who have traveled to this city to build relationships for the benefit of their people.

Nate Poyfair:

My experience during this trip was monumental. I want to compare it to a similar visit to the Ganondagan State Historic Site in the spring of 2023. There, I interacted with historically significant cultural artifacts. During both trips, I was allowed to visit with and hold items that hold deep cultural ties to our Tribe’s history and have survived hundreds of years to help tell such stories.

An exercise I practice in my mind when visiting collections and artifacts such as these is to picture the faces and exchanges. By that, I mean that I try to picture those who created the objects and the time, care, and energy it took to create such art. I picture the process of handshakes and exchanges of such items, and the many, many people who took the care to protect and preserve the items over hundreds of years. This, for me, helps to emphasize the enormous gift we have in seeing and holding such artifacts and the rarity of such items surviving the test of time.

Something unique to this trip was the feeling I had when first seeing the hides through the glass during our initial viewing. Knowing the value these hides present to our community made me emotional when I first saw them and raised my appreciation for the moment. I felt nervous and also really grateful. The nerves came from a feeling similar to seeing a long-lost relative you haven’t seen for many years, and you finally get to hear their story and visit them. The gratuity came from feeling unworthy of such an opportunity. Upon immediate reflection of our visit, I also began to feel a responsibility to community members to teach them about these objects and their value to our people.

These experiences that we, as cultural staff, have are so monumental to our cultural revitalization efforts that it is challenging to put into words. If you have ever lived through an event and thought, “This is a major moment in history,” or “I will never forget this,” then this is how I have felt in experiencing these interactions. As a newer employee of the Cultural Resources Office, I sometimes feel overwhelmed with how to process and understand all of what it means to be Myaamia. Experiencing and learning from objects like these has taught me so much about being Myaamia. I remind myself of the weight of such experiences and understand their importance in my growth and our continued growth as a nation. They possess so much value for our cultural revitalization. I hope many more Myaamiaki can soon experience this and see these items up close.

Future Plans

This trip, although not the first trip nor the last that will be taken by Myaamiaki ‘Miami People’ to visit France, the Branly, and our colleagues there, was a continuation of relationship building that is necessary for the collaboration process. As future plans aim to provide access to hides via exhibitions, our continued interaction with museum curators harbors a better mutual understanding and elevated respect that will aid in the creation of exhibits that respect the sensitive nature of history and culturally valuable artifacts. The future exhibit at the Palace of Versailles commemorating the 1725 delegation and visit to France to meet Louis XV will be opening in the fall of 2025, and we plan to attend the grand opening of this event as collective cultural and governmental representatives of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma.

mihši neewe! ‘Big Thanks!’

Mihši neewe to Dr. Robert Morrisey for his time, dedication, and interest in the history of painted hides.4 Without him, none of these projects would have happened. Mihši neewe to the staff of the Musée du quai Branly Jacques Chirac for their time, commitment, and care that they have taken with the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. Especially Paz Núez-Regueiro, Jonas Musco, Leandro Varison, and Eléonore Kissel for their assistance and the time that they have given us over our visits. Also, mihši neewe to Charla EchoHawk and Dr. Elizabeth Ellis for their accompaniment and friendship during this project. Spending many hours together with our Peewaalia relatives while visiting their ancestral minohsayaki has been life-changing for everyone involved. There are not enough ways for us to express our gratitude to them. kweehsitoolaankiki.

For more information on painted hides, please see articles from our blog here. For a recap of our painted hides workshop, please see this article.

- Visit their homepage to learn more about the Peoria Nation (Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma) – https://peoriatribe.com/ . ↩︎

- These quotations come from C.C.Trowbridge’s interview with Meehcikilita and Pinšiwa in Fort Wayne in the winter of 1824-25. Some of what Trowbridge recorded regarding our language is contradictory, but evidence from 300 years of language sources makes it possible to parse through the confusion in his record. In the opening of this text, Trowbridge recorded “For instance, the Miamies understand perfectly the Kaskaskias, Peorias, Weas & Piankeshaws, because those tribes have all descended from them. And the difference of dialect is scarcely more than between the present Parisian and the Canadian French.” Later in the text he recorded more details on our relationship: “The Piankeshaws, the Wēēaus (in Miami Wüautōnoakee) and the Kaskaskias (Mekoateeaukee) are descendants from the Miamies. The two first separated from them at St. Joseph’s and the latter, a different tribe originally, and very poor, were discovered on the Wabash, made tributary to the discoverers and finally incorporated with them, but after sometime they separated again & divided. From these came the Peorias. These three nations speak the Miami language, but the latter by having been separated from the parent stock some time have changed their language so that there are now but few Miami words in their language.–They term these tribes their younger brothers and they claim no other actual relatives, but they have many adopted ones, viz, their elder brothers the Chippeways, their Grand fathers the Delawares, their elders brothers, the Wyandots, the Ottawuwas their elder brothers, the Potawatamies the same and the Shawnees brothers.” What Trowbridge meant by “few Miami words in their language” is unknown, but in the 1820s the Peewaalia and the Myaamia continued to speak different dialects of the same language. This relationship continues to today as the Peewaalia and Myaamia speak a language with slight differences of pronunciation and a few different but understandable words for things that we encountered after contact with Europeans. C. C. Trowbridge, Meearmeear Traditions, ed. by Vernon Kinietz (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 2, & 12-13.

↩︎ - Richard N. Ellis and Charlie R. Steen, “An Indian Delegation in France, 1725,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984) 67, no. 4 (1974), 387. ↩︎

- If you want to read more about Dr. Morrissey’s historical work, check out his most recent book People of the Ecotone: Robert Michael Morrissey, People of the Ecotone: Environment and Indigenous Power at the Center of Early America, Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2022). ↩︎

Leave a comment