Revitalization of language and culture has been a primary focus of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma over the past 30 years. Prior to this, Myaamiaataweenki, ‘the Myaamia language,’ had ceased to be spoken by Miami people. With no speakers, archival linguistic documents became the source of revitalization efforts.

During the summer of 2024, the Miami Tribe’s Indigenous Language Digital Archive (ILDA) reached 100,000 entries. This achievement was a result of the dedicated work of the staff of the Office of Language Research at the Myaamia Center. The ILDA database provides much of the data that feeds the Myaamia dictionary that many Myaamiaki use on a daily basis. This important work is key to the continuing growth of language use across the community.

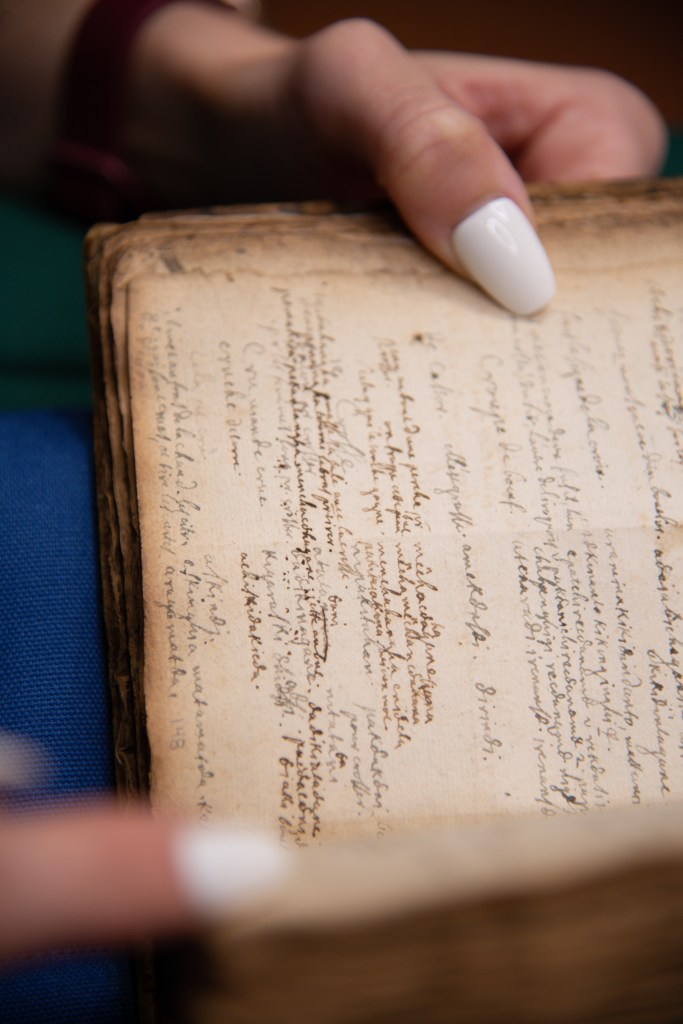

Several key archival documents have been used to revitalize the language. One of those critical sources is Pierre-François Pinet’s dictionary, discovered in 1999 by Michael McCafferty.

Various French Jesuits wrote this dictionary between 1695 and 1700. Pinet lived amongst a large village of the Waayaahtanwa ‘Wea’ tribe at the Guardian Angel Mission (located within the region that today we call Šikaakonki ‘Chicago’). The Waayaahtanwa were originally a subgroup of the Myaamia, but later in the 1800s, they merged politically with our relatives, the Peoria Tribe. At the Guardian Angel Mission, Pinet and other Jesuits compiled language entries of Myaamiaataweenki into this dictionary. It and other resources were systematically transcribed and translated as a part of the Miami Tribe’s ongoing language reclamation efforts.

In September 2024, the Newberry Library invited a small group of Myaamia tribal members and employees – George Ironstrack, Nate Poyfair, Logan York, Morgan Lippert, and Madalyn Richardson – to view the Pinet dictionary privately before going on display in the “Indigenous Chicago” exhibit at the Newberry Library of Chicago, Illinois. It was loaned from the Archives De La Compagnie De Jésus “Archive of the Jesuits,” in Québec, Canada, to be on display in this collaborative exhibit, which “centers indigenous voices, laying bare stories of settler-colonial harm, and gesturing Indigenous futures.”

The exhibit highlights the homelands of Indigenous peoples in Chicago since time immemorial, including those of “Neshnabé (Potawatomi, Odawa, Ojibwe), Illinois Confederation (Peoria and others), Myaamia, Wea, Sauk, Meskwaki, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Kickapoo, and Mascouten.” Not only is Chicago a “historic crossroad,” but a current “home to an extensive urban Native community.”

Various individuals meticulously wrote the dictionary over a period of a few decades. It was compiled to translate Myaamiaataweenki into French to assist the Jesuits in communicating with and converting Myaamia and Inohka ‘Illinois’ people to Catholicism. It featured tiny scripts by different hands scrawled with pencil, pen, and the occasional ink blot that disrupted the neatly organized pages.

The Newberry and Archives of the Jesuits’ staff allowed the group to handle and interact with the object for several hours, and the group enjoyed seeing it in person for the first time. Ironstrack, York, Poyfair, Lippert, and Richardson enjoyed turning the pages and picking out recognizable words in Myaamiaataweenki or French. Some were easily recognizable, while others revealed dialects in the French translators or Myaamia speakers. The group also laughed while sharing some humorous historical accounts between the French and Myaamia or long-told stories about them.

Following this, the group was treated to a catered lunch and taken on a grand tour of the Newberry led by Analú López, Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator of American Indian and Indigenous Studies. The library features extensive archival storage and multiple floors of accessible materials. One of the library’s largest collections are primary sources by Edward E. Ayer. His writings, drawings, and accounts documented Native-American life during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Topics covered within the Ayer collection were noted to include “…Native American archaeology, ethnology, art, and language; the history of the contact between Europeans and native peoples; voyages, travels, and accounts of early America; the development of cartography of the Western Hemisphere; and the history of the aboriginal peoples under the jurisdiction of the U.S. in the Philippine Islands and Hawaii.”

Will Hansen, Curator of Americana at the Newberry, also set aside a collection of photos of Myaamia people, illustrations of individuals, a Wea primer, and a letter from Dunn to Ayer about the Myaamia for the group to view privately.

It was incredible to see the history of Myaamia captured by others over time, to see it as it persists today, and to share in the history still being made. Opportunities like these are a gift to our cultural researchers and tribal citizens that allow Myaamiaki to explore their history and continue to expand on historical, cultural, and linguistic knowledge. The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma would like to say mihši neewe ‘Big Thanks’ to the Newberry Library for helping to facilitate the interaction with the Pinet Dictionary and recognizing our rich tribal history along the southern shores of Lake Michigan.

Read more about this visit to the Newberry Library and the “Indigenous Chicago” exhibit here.

Credits

Feature photo by Madalyn Richardson, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma.

Originally published under the title “Pinet Dictionary and Visit to the Newberry Library” in the Aatotankiki Myaamiaki newspaper, 2024. miamination.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Vol-18-No-2-Fall-3-2024-1.pdf

Leave a comment