The Myaamia Heritage Award Program (HAP) undoubtedly affords Myaamia college students an incredible opportunity that, for some, would not otherwise be possible. The tuition waiver for some students makes college possible or, at the very least, more accessible and affordable. Additionally, the series of courses about language and culture currently offers the highest level of structured or formal education for Tribal citizens. However, what does this translate to practically in terms of outcomes?

The Office of Assessment and Evaluation is tasked with researching the impact that educational programming offered by the Tribe and Myaamia Center has on community members, and the HAP students are one group we seek to understand. With direction from Tribal Leadership, we are typically interested in four outcomes: (1) academic attainment, (2) nahi meehtohseeniwinki ‘living well’, (3) connectedness, and (4) National/Tribal growth and continuance. It is important to note here that while these are pieced apart for the sake of research and this article, they are all highly interrelated. But, for the sake of this blog post, let’s dig into each one!

Academic Attainment

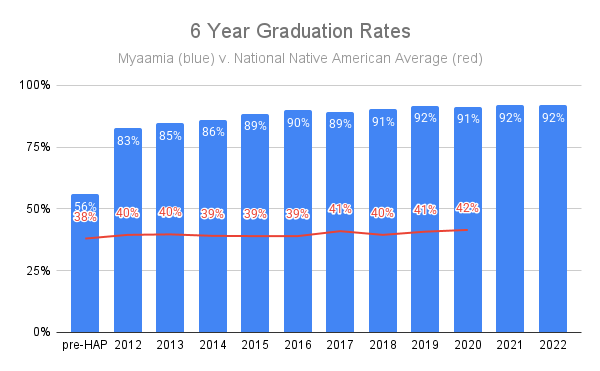

The first outcome, academic attainment, is always my favorite to talk about at conferences because I get to share our flashy statistics that never fail to impress. Myaamia students have been attending Miami University as part of the HAP since 1991. However, the actual courses tied to the HAP as we know it today didn’t start until 2001. This offers us the opportunity to compare graduation rates between 1991-2001 (where students received a tuition waiver, but no Myaamia educational curriculum) with those since 2001 (where students receive both a tuition waiver and Myaamia educational curriculum). Theoretically, the primary (though admittedly not only) difference between these two groups is the inclusion of the curricular and extracurricular components offered by staff at the Myaamia Center.

For students in that initial group, the 6-year graduation rate was 56%. This is higher than the average 6-year graduation rate amongst all Native American/Alaska Native students at 4-year colleges/universities in the United States, which hovers in the low-mid 40th percentile range pretty consistently. However, today in 2025, we are at a graduation rate of 89.5% (which is actually down from 91% pre-COVID, likely due to the effects of COVID on students universally). While not the only factor, it is fair to conclude that the educational offerings put forth by the HAP are making a difference in the lives of our students. If I had to guess, the other outcomes of interest are interacting with their academic lives (well-being, sense of connection, etc.) and supporting the success of our students.

While a fun statistic, graduation rates are not the only way to approximate academic attainment. From a Myaamia perspective, academic attainment means acquiring knowledge and using that knowledge to contribute in a meaningful way to the community. Someone on the OAE team has interviewed all Myaamia students since 2012 at two timepoints: first when they enter the HAP and again when they are leaving. These interviews undoubtedly reveal that students experience an evolution of their knowledge. Regardless of their experiences when they enter the program, students expand their knowledge base by participating in the HAP courses. Some are starting fresh, and everything they learn is new. Others come in with an existing knowledge base but hone that knowledge over time. Not only that, but through interacting with other (non-Myaamia) professors and peers at the University, they learn how to speak about their Myaamia culture in a way they feel confident about.

Further, many students are able to identify ways they can merge their personal/professional interests with their Myaamia identity. They engage in a Senior Project that requires this, and some students go above and beyond to engage in projects and contribute their academic knowledge toward the Myaamia community. This is all academic attainment.

Nahi meehtohseeniwinki ‘living well’

We are also interested in how educational programming, like the HAP, impacts individuals’ ability to live well, which we refer to as nahi meehtohseeniwinki in Myaamiataaweenki. The OAE recently undertook a project to create a theoretical framework to help us understand what nahi meehtohseeniwinki looks like from a Myaamia perspective. When we administered the living-well survey to the Myaamia community, we were able to identify which Tribal citizens were college students and, of those, which are members of the Heritage Award Program at Miami University. Again, this gave us the ability to compare HAP students with other Myaamia college students who do not receive the immersive cultural education.

When comparing the differences between these two groups, we found that students in the HAP reported significantly higher levels of all Myaamia knowledge competencies – in terms of having more knowledge, continuing to learn more, and engaging/participating in that knowledge. Additionally, HAP students reported higher levels of social wellness. Sometimes it can be just as helpful to look at where there is no difference between groups; in this case, HAP students and other Myaamia college students showed no differences in Myaamia community values nor in physical, emotional, spiritual, or ecological wellness.

This tells us that the HAP offers unique contributions to students’ overall well-being. Receiving this educational opportunity connects individuals to a Myaamia knowledge system and to one another, supporting their ability to live well in a Myaamia way.

In addition to the data collected from this measurement tool, there are other indicators of well-being that we have observed for some time. One’s identity plays an important role in their ability to live their best life. Students in the HAP have long indicated that the experiences they have as part of the program help them understand who they are as a Myaamia citizen, how that interacts with their other identities, and also give them the means to express that identity to the world. This comes out through artistic expression, community engagement, giving back to the community, and through their family and careers. One of the most common sentiments I have heard in the interviews is that students always knew they were Myaamia before coming to the HAP, but participating in the program taught them what that meant and gave this identity some knowledge and legitimacy to ground it.

Connectedness

The third outcome is an individual’s sense of connection and ability to engage with the community. Connectedness involves a perception or feeling of belonging to a particular community. It is important to note that this feeling is bidirectional in that a person both feels like they are welcomed by and that they are a part of the community.

A First Nations scholar, Dr. Angela Snowshoe (non-status Ojibwe/Metís), and her colleagues created the cultural connectedness scale that gives a sense of how connected people are/feel to their Tribal community. We modified this scale to fit a Myaamia perspective and have given it to all HAP students since 2018. Every single cohort, as well as the overall group of HAP students as a whole, demonstrates a significant increase in their connectedness when we compare their scores as they enter the program to their scores as they leave the program. The interviews again corroborate these data – HAP students consistently talk about feeling connected to one another and the community as a whole.

For example, in an interview at the end of their tenure in the program, one student said, “to me [being] Myaamia means to have connections with everyone. Like I’ve said, I’ve met people from all over the country who — they have had nothing in common but we’re both Myaamia. That can bring us together through dance, and through music, through the language, and through games, just all these different aspects of our culture.”

National/Tribal Growth and Continuance

Another theme that emerges from the interviews with students is a desire to give back to the Myaamia community. During their time in the HAP, students often internalize the value of giving back to the community. Not only is it an expression of a community value, but it also seems to be tied to a desire to contribute to a community that has afforded them many opportunities.

While an exhaustive list of ways that alumni of the HAP give back to the community is not feasible within this blog post, we do know that we have folks who: work for the Tribe, work for the Myaamia Center, engage in graduate and academic research on topics pertaining to the Tribe, hold leadership positions within the Tribe, sit on the Miami Nation Enterprises board, are formal storytellers, and more. Not all students can give back in these “formal” roles, and many give back within their families and local communities through education, community building, and more. All of these roles and all of these contributions benefit our community and are necessary for the future of the Nation.

I want to be clear that the HAP is not the only way that folks can experience these positive outcomes; there are so many paths toward these ends. However, the HAP does make this a more streamlined and easier process by which Myaamiaki ‘Myaamia people’ can achieve these outcomes.

This work is longitudinal and ongoing and ultimately informs ways we are able to promote positive outcomes in students and even the broader Tribal community. In the future, I would love to better understand the process that gets students to these outcomes. This would allow us to facilitate the development of those same steps in other contexts (Summer Programs, educational programming, outreach, etc.) to promote the well-being of all Tribal citizens.

Leave a comment