When Daryl Baldwin and his family began learning Myaamiaataweenki ‘the Miami language’ after it had been silent for 30 years, they faced a major challenge. No learning materials existed. There was no “Myaamia dictionary” or publications about the language.

However, with the help of Dr. David Costa, Daryl would soon learn that a plethora of information about the language was stored in archives across North America.

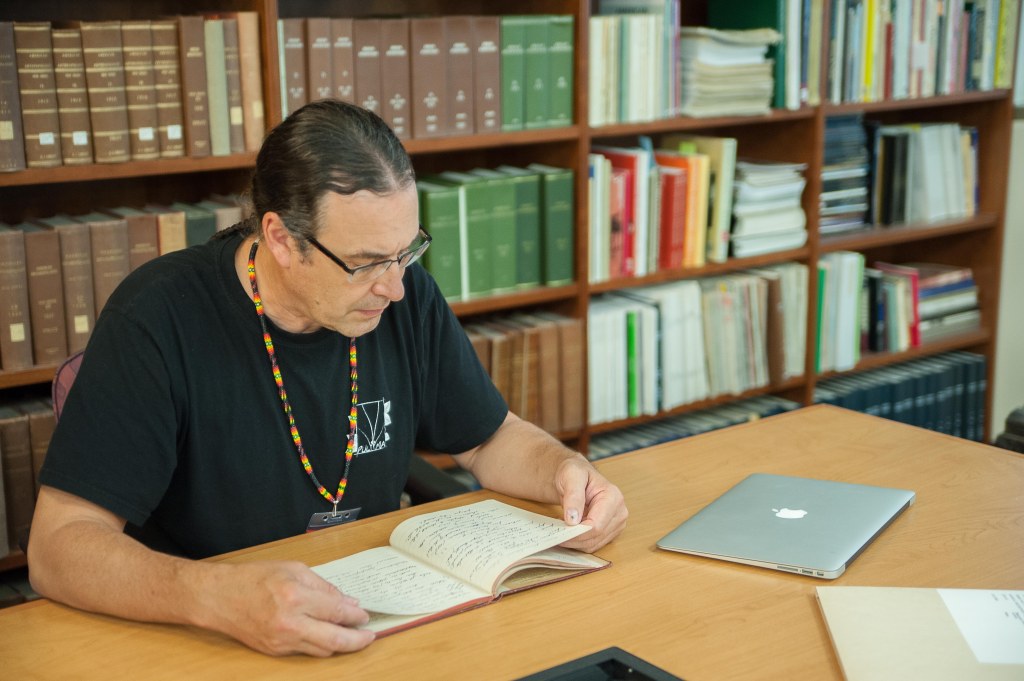

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Daryl and David, with support from Julie Olds from the Miami Tribe’s Cultural Resource Office, uncovered large collections of documents on Myaamiaataweenki, spanning 250 years.

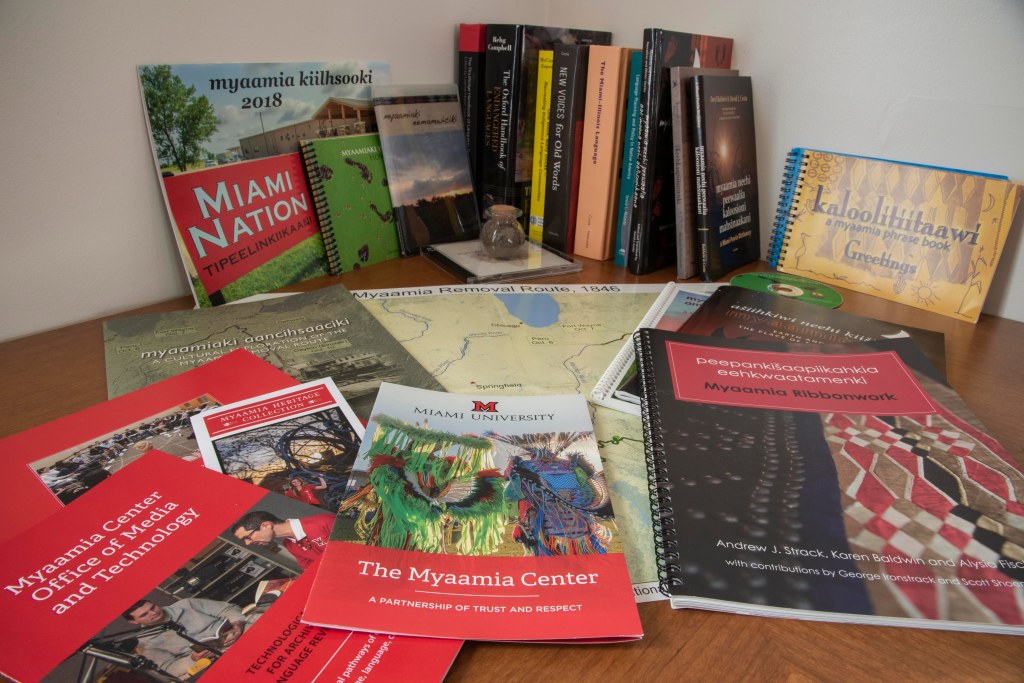

Today, using those historical records to create learning materials is at the heart of the Myaamia Center’s mission. But how does that actually happen?

The process involves careful research, linguistic analysis, and community collaboration, driven by a team of linguists, researchers, and educators from the Myaamia Center and the Miami Tribe’s Cultural Resource Office.

From Document to Dictionary:

1. Find

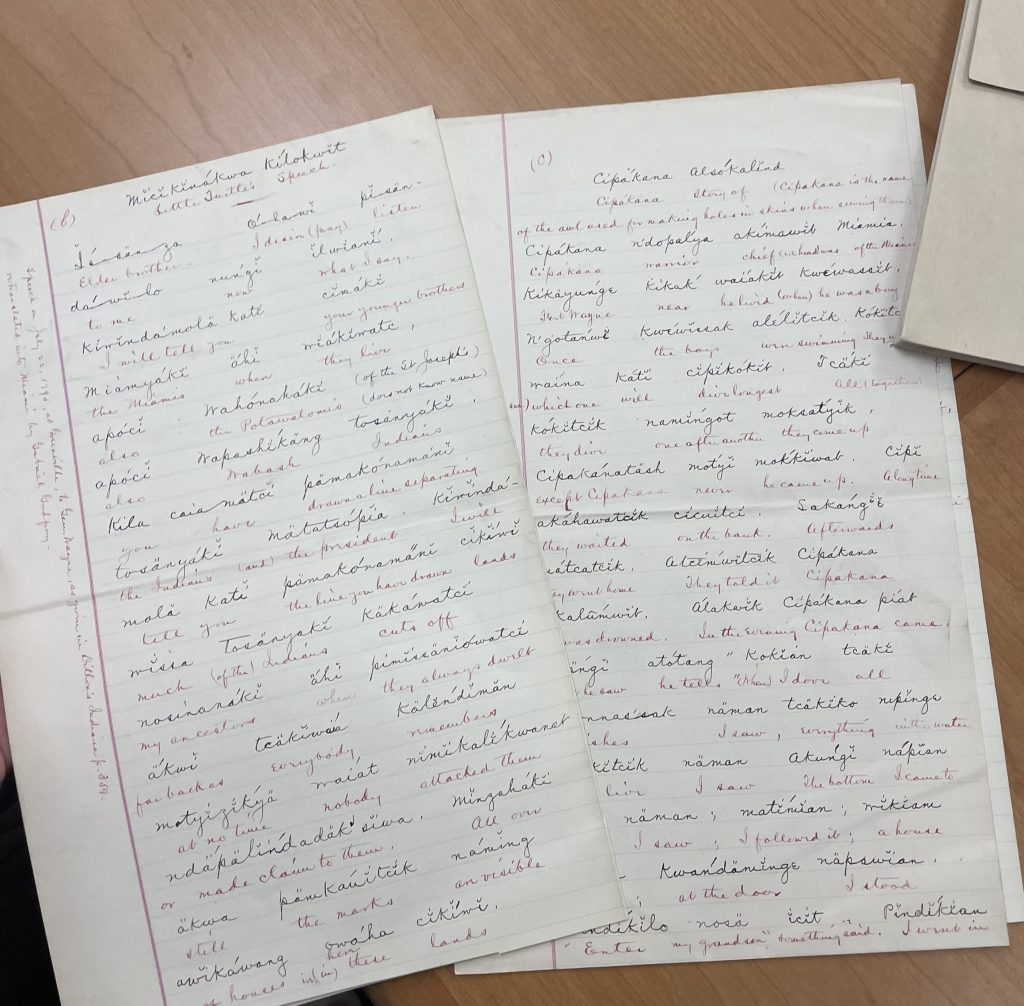

Since the 1600s, various people have recorded information about Myaamia language and culture. These records are kept in libraries and archives across the United States and Canada.

2. Copy

Once the team locates these documents, they make high-quality photos and scans. This allows the researchers to study the records without the original copies leaving the archives. The Myaamia Center has gathered thousands of pages of these digital copies so far!

3. Transcribe

Old handwriting can be messy, faded, and very hard to read. In this step, team member Carole Katz, carefully types every word exactly as it appears in the original record. This “transcription” turns the messy script into a clear, digital text that is ready to be analyzed.

4. Translate

Many of these historical records aren’t in English, but instead were written by French speakers hundreds of years ago. A crucial step is to translate these French documents into English so that today’s researchers and linguists can understand them.

5. Study

Once we have a clear, translated text, the linguistic experts get to work. They analyze the words and sentences to determine their meanings and to understand the grammatical rules of the language. This is where the intricate building blocks of the language are rediscovered.

6. Interpretation

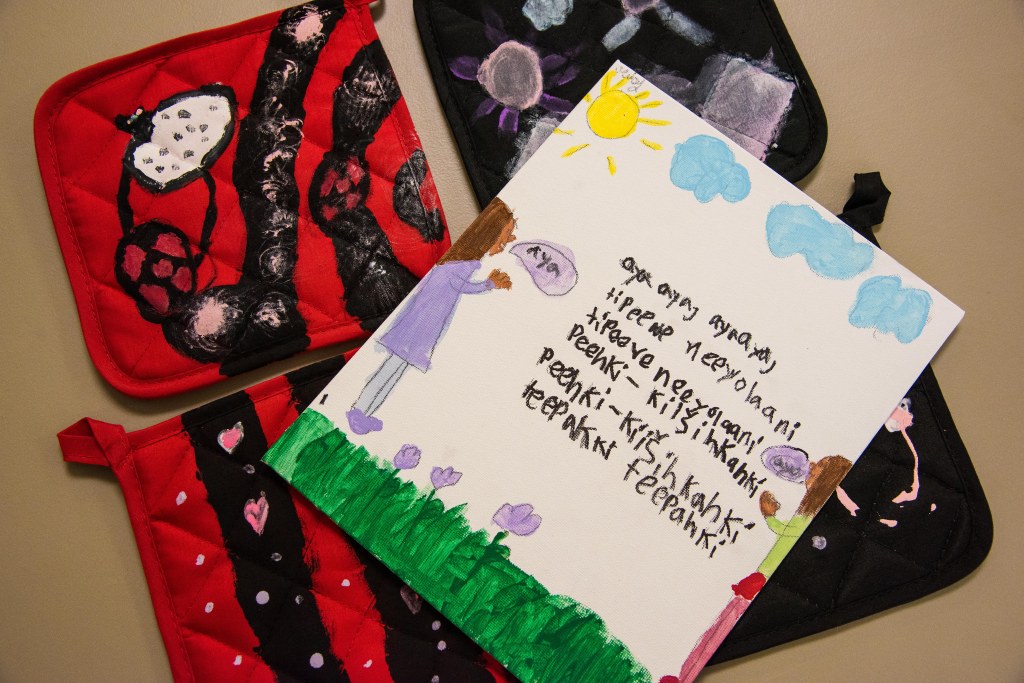

Linguists, language speakers, and community members work together to determine how these words and phrases can be best used in our current context. This step bridges the gap between the historical record and the living community.

7. Share

Language revitalization wouldn’t be possible without sharing this information with the community. The words and phrases are added to the online Myaamia dictionary, making them available to everyone in the community. Educators from the Miami Tribe also use the online dictionary to create new, engaging learning materials for all ages.

ILDA: Our Digital Homebase

Every step of this process is saved in the Indigenous Languages Digital Archive (ILDA).

The archive side of the database serves as a digital home base, preserving every scan and translation for community researchers. Meanwhile, the online Myaamia dictionary serves as the public-facing learner tool for everyone in the community.

As of October 2024, this effort represents over 30 years of work, and the ILDA database holds more than 100,000 Myaamia words and phrases. But the true measure of this work isn’t a number in a database, it’s the sounds of Myaamiaataweenki being spoken throughout our community. This “archive-to-dictionary” pipeline is how we reconnect with our language and bring it home.

The revitalization of Myaamiaataweenki would not be possible without the work of the Office of Language Research at the Myaamia Center. This is an intersectional team with two linguists, Dr. David J. Costa and Dr. Hunter Thompson Lockwood, and a transcriptionist, Carole Katz. They regularly collaborate with Michael McCafferty from Indiana University, who performs translation work, and the team is overseen by Daryl Baldwin, executive director of the Myaamia Center.

Learn more about archives-based language revitalization work within the Miami Tribe:

Leave a comment