For about a millennium, Myaamiaki ‘Myaamia people’ have cultivated a relationship with their environment through agriculture. Like hunting, this is a practice that never entered dormancy. Throughout its history, miincipi, the generic term for “corn” in Myaamiataaweenki, appears in many historical sources.

Given its importance, Myaamiaki have used personal names that reference miincipi ‘corn.’ Here are some examples of historical Myaamia people:

Kitahsaakana ‘parched corn’

Noohkiinkweemina ‘flour corn’

Wiihkapimiincipa ‘sweet corn’

Waapanaakikaapoohkwa ‘corn tassel woman’

In the twentieth century, the heirloom variety that survived was a white flour corn. That makes sense, as the Miamis were known for it. As the commandant of Detroit observed in the early eighteenth century:

“The miamis are Sixty leagues from Lake Esrié. They number 400 men, all shapely and well tattooed. They have abundance of women. They are very industrious, and raise a kind of indian corn which is unlike that of our tribes at Destroit [sic]. Their corn is white, of the same size as the other, with much finer husks and much whiter flour.”1

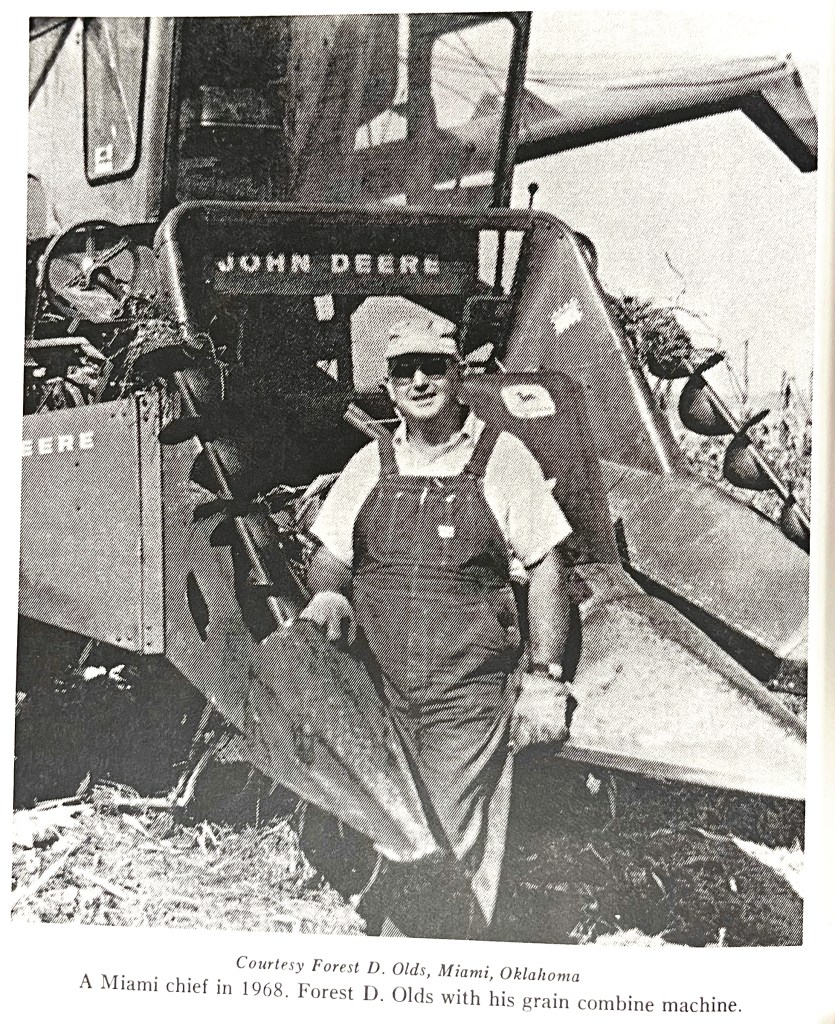

One of the historical source bases that helps indicate the importance of Myaamia miincipi is the soldier journals kept during the Mihši-maalhsa Wars. Having marched north from Cincinnati to what is now Fort Defiance, Ohio, the famed traitor, soldier, and general scoundrel James Wilkinson wrote in 1794 that “we have destroyed prodijeous [sic] quantities of Corn.”2 William Clark (the explorer and buddy of Meriwether Lewis) was impressed with the “handsome View up & down the Rivers, the Margins of which as far as the Eye can see are covered with the most luxurient groths (sic) of Corn.”3 These communities were not only Myaamia, but also Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, and others.

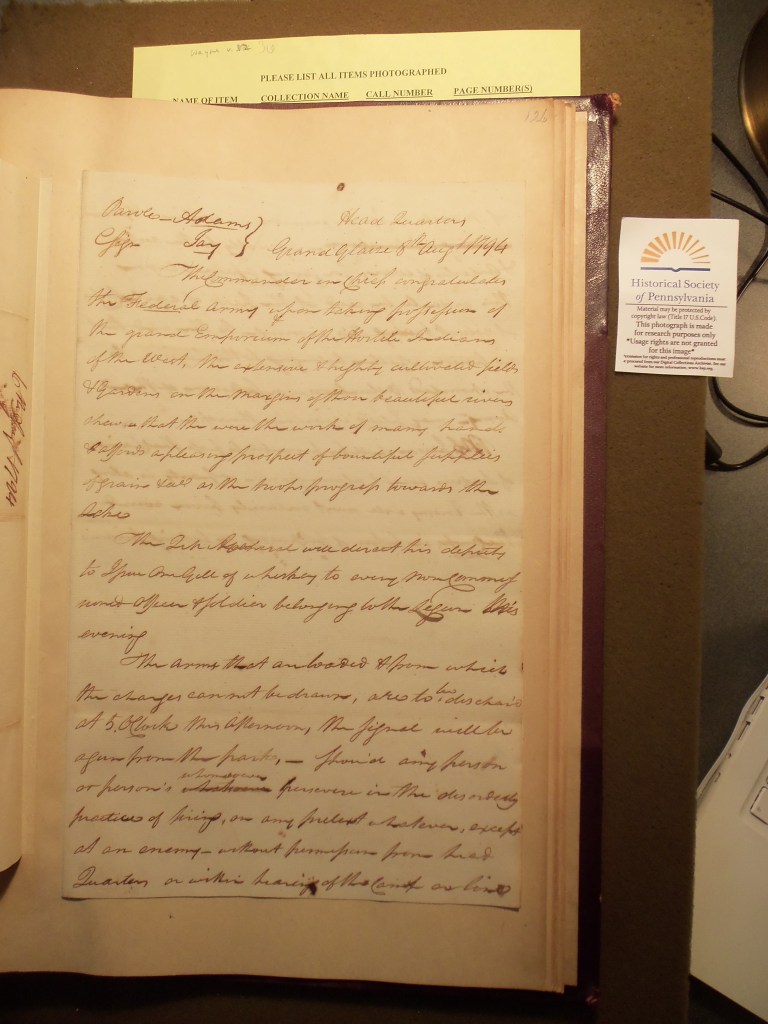

What follows are two primary sources, one written by a Lieutenant named John Boyer, the other written by Brig. General Anthony Wayne. The U.S. Army was marching north to what is now Fort Defiance, Ohio, in late summer 1794.

John Boyer

8th August.

Proceeded on our march to this place at five o’clock this morning, and arrived here at the confluence of the Miami and Oglaize rivers at half past ten. This place far excels in beauty any in the western country, and believed equaled by none in the Atlantic States. Here are vegetables of every kind in abundance, and we have marched four or five miles in cornfields down the Oglaize, and there is not less than one thousand acres of corn round the town.

10th August.

The troops in good spirits. No interruption from, or account of, the enemy. We have plenty of vegetables.

Anthony Wayne

We have gained possession of the grand emporium of the hostile Indians of the West, without loss of blood. The very extensive and highly cultivated fields and gardens, show the work of many hands. The margins of those beautiful rivers, the Miamies of the lake [Maumee River], and Au Glaize, appear like one continued village for a number of miles, both above and below this place; nor have I ever beheld such immense fields of corn, in any part of America, from Canada to Florida.4

John Boyer again

24 August.

In this day’s march we destroyed all the corn and burnt all the houses we met with, which were very considerable.

26 August.

The legion continued their march, and after burning and destroying all the houses and corn on their route, arrived on this ground at two o’clock.

28 August. Fort Defiance.

There is corn, beans, pumpkins, etc, within four miles of this place, to furnish the troops three weeks.5

Miincipi has been central to Myaamia cuisine, labor, the calendar, historical change, and other aspects of culture. William Wells stated in about 1812: “The Indians have a variety of dances and games. The war dance, the corn planting dance, the new corn dance, the otter dance, the bear dance, the begging dance, the morning dance, and the Pipe dance.” Yet Trowbridge’s informants (Pinšiwa ‘Jean Baptiste Richardville’ and Meehcikilita ‘Le Gros’) told him in the 1820s: “There are no feasts connected with hunting, or upon the planting or ripening of the corn and vegetables, as is practiced among the Delawares, nor does the nation tribe or village ever feast together for any purpose whatever.”6 Given that their tribal relatives have (and still do) practiced communal harvest rites, it seems reasonable that Myaamia have long participated in these ceremonials, even if by the 1820s they did not claim them as their own.

There are a couple of stories that deal directly with miincipi. One was recorded by Clarence Godfroy in the twentieth century. All of Clarence’s stories should be interpreted as products of his context. For example, Clarence Godfroy’s recorded stories were primarily intended for his non-Miami audience, and so he made the narratives legible for those circumstances.

A long time ago, the people were starving, and they sent out people to find food. (Clarence called these searchers “prophets” in his recorded version.) One returned with new knowledge.

[The prophet/searcher] said, “I met a very handsome man who wanted to know why I was in the wilderness alone.”

“I have come to talk to the Great Spirit about the famine in my country,” the prophet told the stranger.

The handsome man said, “You must fight a duel with me, kill me, and bury me upon this spot.”

“You are too handsome a man for me to kill. You have not wronged me and I cannot fight you,” answered the prophet.

The prophet who had been searching for food did duel the handsome man, killed him, and buried his body. Miincipi grew there, and the prophet brought the stalk of corn back to his people.

“The Indians called the food MEN-JIP-IE,” Godfroy finished.7

Grand Traverse Band also had a story about the Miamis and miincipi. Once, a town of Miamis planted a huge crop and harvested it, saving plenty in caches in the ground.

“The crop was so great that the Miami young men and youths were regardless of it, for many ears of corn remained on the stalks; the young men commenced playing with the shelled cobs, and threw them at one another, and finally broke the ears on the stalks, and played with them in like manner as with the cobs.”

In the ensuing winter, this band of Myaamiaki fared poorly in their hunt, and began starving. They found their caches empty. One hunter found a decrepit old man, who gave him miincipi soup, but told him “Your people have wantonly abused and reduced me to the state you now see me in: my back-bone is broken in many places.” Schooling the hunter, the old man told him: “This is the result of the cruel sport you have had with my body.” 8

All of these historical sources indicate the centrality of miincipi to Myaamia life over the generations. Keep an eye out for future posts from Dr. Hunter Thompson Lockwood about language for miincipi.

- Jacques Charles Sabrevois de Bleury, c. 1718, in Wisconsin Historical Collections, 16: 372-75. ↩︎

- Milo M. Quaife, ed., “General James Wilkinson’s Narrative of the Fallen Timbers Campaign” in Mississippi Valley Historical Review 16, no. 1 (1929): 89 ↩︎

- R. C. McGrane, ed., “William Clark’s Journal of General Wayne’s Campaign” in Mississippi Valley Historical Review 1, no. 3 (Dec. 1914): 424. ↩︎

- “Memorandum of Occurrences in the expedition under General Anthony Wayne 1794, written by Nathanial Hart of Woodford,” Draper Manuscripts 16U: 68. ↩︎

- John Boyer, “Daily Journal of Wayne’s Campaign,” in The American Pioneer: A Monthly Periodical 1 (Cincinnati: 1842): 316-320. ↩︎

- C. C. Trowbridge, Meearmeear Traditions, ed. By Vernon Kinietz (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938) ↩︎

- Clarence Godfroy, Miami Indian Stories (Winona Lake, IN: Light and Life Press, 1961), 24-25. ↩︎

- Story told by Ogimawish, recorded in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Philadelphia, 1855) 5: 193-195. ↩︎

Leave a comment