Each year, the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma sends out Myaamia Kiilhswaakani ‘Myaamia lunar calendar’ to Tribal households. This annual calendar follows the ecological changes each month is named after.

What is a lunar calendar?

To begin, you must understand the motion of tipehki kiilhswa ‘the Moon.’ Tipehki kiilhswa revolves around the Earth once approximately every 29.5 days. Myaamiaki ‘Myaaamia people’ describe the visible changes the same way we would the life cycle of a plant. At the start of the month, the Moon sprouts (saakiwa kiilhswa), then continues growing until it is full (waawiyiisita kiilhswa). At that point, it begins dying away until it is no longer visible (neepiki kiilhswa). Since this pattern is reliably predictable, it is used to track the passage of time.

Our calendar system organizes the year into 12 months based on observable ecological changes throughout the year. Several months are named for the breeding season of animals. One example is wiihkoohwia kiilhswa, named after the Eastern Whippoorwill (Antrostomus vociferus). Wiihkoohwia does not build a nest; instead, it lays eggs on the ground where it is well camouflaged. You can learn more about each month’s name by visiting our lunar months page.

Photo from Adobe Images.

How does the Myaamia lunar calendar system work?

Since the calendar system is organized around ecological observations, we occasionally need to adjust the calendar so the month names and their associated changes remain aligned. This is done by adding a leap month, waawiita kiilhswa ‘lost moon’, approximately every three years. Since there are no ecological ties for waawiita kilhswa, it is inserted in the middle of winter when not much is happening.

We are able to predict when it is time to add waawiita kiilhswa by watching pahsaahkaahkanka ‘the summer solstice’. Pahsaahkaahkanka is the longest day of the year and when the Sun is at the highest point in the sky it will reach in the year. This event needs to happen during paaphsaahka niipinwiki kiilhswa ‘mid-summer moon’. As the video below demonstrates, pahsaahkaahkanka will slowly move closer to the end of the month, and eventually fall into the next month, without the addition of waawiita kiilhswa.

It may not seem like a big deal based on that video, so let’s think of it another way. Wiihkoowia kiilhswa is typically when Myaamiaki plant corn. As a ground-nesting bird, they will not lay their eggs until the ground is no longer frosting. If we know they are laying eggs, then we know it’s safe to plant. The corn then grows for several months and when it is kiišinkwia kiilhswa ‘green corn moon’ (the one after paaphsaahka niipinwiki), the corn should be in its milk stage, where it can be eaten off the cob. If the months are no longer aligning with their ecological changes, then our timing will be off for events such as corn planting.

How did we come up with the month names?

The names for our months were shared by our ancestors with outsiders who documented our language. We have several sets of month names, but we looked at two records specifically for our contemporary calendar: Dunn and Trowbridge.

In the 1900s, Jacob Dunn worked with Gabriel Godfroy in Indiana. Godfroy shared names for each of the 12 months in our calendar that were nearly identical to a list that was shared with C. C. Trowbridge nearly 80 years earlier. The difference was only one month in the middle of summer. As a result, the decision was made to use Godfroy’s calendar because it was consistent and represented our homelands along the Wabash River.

How has the calendar changed?

When researchers first began looking at the calendar system, each Myaamia month name was assigned to a Gregorian month. With more research, each Myaamia month was once again connected (as closely as possible) to the time of year associated with its ecological ties. Wiihkoowia was assigned to June in Dunn’s records, but they tend to lay their eggs in May-June, so that is when you will see wiihkoowia kiilhswa in Myaamia Kiilhswaakani.

As we teach our community about the calendar, it is important to note that our environment has changed and continues to change. Our calendar has always been adapted to meet our needs as a people. For example, our current calendar has a month named for the Eastern American elk (Cervus canadensis canadensis). This species is now extinct, but the decision was made to keep the month name as a way to remember the past. This begs the question of whether or not to rename the month. It’s possible that future Myaamiaki will decide that a change is needed.

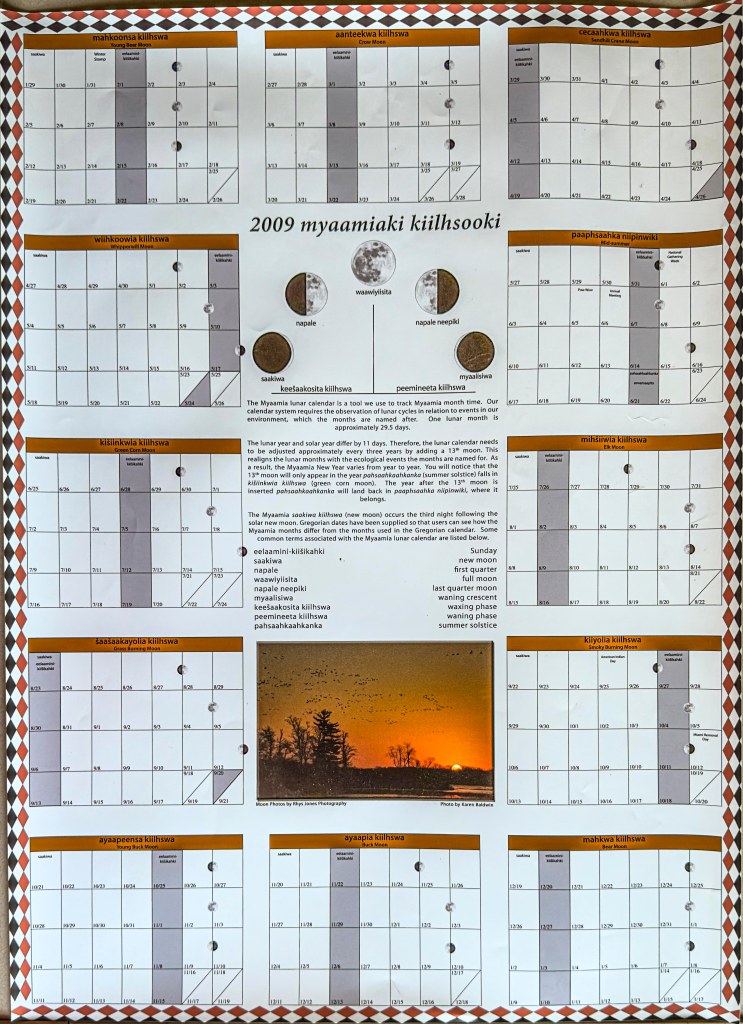

In the meantime, we have continued to adapt how we share Myaamia Kiilhswaakani since it was first printed in 2009. That first version was a poster that showed all 12 months and had a short explanation of how our calendar system works.

In 2010, waawiita kiilhswa was added to the calendar for the first time. As far as we can tell in the records, there was never a name for a 13th month. Instead, our ancestors would have corrected the calendar as needed to keep the months and their associated ecological changes aligned. However, as we began the process of printing a calendar, we needed a way to show the realignment, and that is how waawiita kiilhswa came to be named.

Since 2010, small changes have occurred to the calendar, such as updating the front matter and tipehki kiilhswa icons, adding historical and contemporary events, and sharing images of our community. The biggest change to date, however, occurred in 2022 when the calendar was officially titled Myaamia Kiilhswaakani. Prior to this, each cover used the plural for months, “Myaamia Kiilhsooki”.

While printed calendars are a great visual for the wall, we recognize that they may not be the most useful for people who use electronic devices regularly. In 2024, we launched the first version of a digital calendar on Šaapohkaayoni: A Myaamia Education Portal. This allows us to provide more information and RSVP links to calendar events and can be more responsive to community needs since edits are instantly available to users.

Leave a comment