meekaalankwiki mihši-maalhsa – mikaalitioni waapaahšiki siipionki

The Mihši-maalhsa Wars – Part III – The Battle of the Wabash

This post is the third of a five-part series on the history of our wars with the Mihši-maalhsaki (Americans), which occurred from 1778-1794 and from 1812-1814. This third post focuses on the Battle of the Waapaahšiki, also known as St. Clair’s Defeat. If you want to hear the pronunciation of the Myaamia terms in this article, please visit our online dictionary at: www.myaamiadictionary.org

In Part II of this series we looked at the General Josiah Harmar’s invasion of our homelands and his assault on the Myaamia, Shawnee, and Delaware villages along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi (Maumee River). The villagers forced Harmar to retreat from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi, but only after his forces burned five villages and destroyed over 20,000 bushels of corn, beans, and squash. In the harsh winter of 1790-91, the loss of homes and food had a horrific impact on our ancestors and their relatives in the Shawnee and Delaware villages.

Over the spring of 1791, the villages along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi began to slowly recover. Some Shawnee and Delaware people chose to rebuild their villages farther to the east on the Auglaize River near its confluence with the Taawaawa Siipiiwi. Additionally, some Delaware relocated to the south on the Waapikamiiki (White River, Indiana). Food remained a problem for the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villagers through the spring and into the early summer. The situation worsened as men from all over the Great Lakes gathered along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi in response to the rumors that another army of Mihši-maalhsa would march north from Fort Washington (Cincinnati).

Early in the summer of 1791, there were approximately 2,000 adult men gathered along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi. Nearly half of these men came from allied villages to the north and west of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi. British Indian Agents distributed corn, gunpowder, and lead along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi in an attempt to assist the villages with their food shortage. By the middle of the summer, the villagers and their assembled allies had already consumed five hundred bushels of British corn, and British agents began appealing to officials for more support.[1] Publically, the British claimed to be issuing the food and hunting supplies to help convince the villagers to seek peace with the United States. Privately, some British officials hoped the food and supplies would help sustain military resistance, but this was increasingly difficult. By early June, the lack of food forced the Sauk and Meskwaki to leave the Taawaawa Siipiiwi and return to their villages.[2]

Around the time the Sauk and Meskwaki departed, the allied villages learned of an attempt on the part of the U.S. to negotiate a settlement. The Delaware captured an American who reported that Colonel Thomas Procter attempted to reach the Taawaawa Siipiiwi in early May. His goal was to urge the villages to negotiate for peace.[3] He was instructed to tell the Myaamia, “Call in your [war] parties, and fly with your head men to Fort Washington for a treaty.” However, his trip was poorly planned and terribly executed. At the beginning of his trip, the Pennsylvania militia abused his Seneca guides, and the effort collapsed on the eastern shores of Lake Erie as the British refused to transport Procter across the lake. The Taawaawa Siipiiwi villagers saw this effort for what it was: a half-hearted attempt to buy time for the American Army to organize a second invasion of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi.

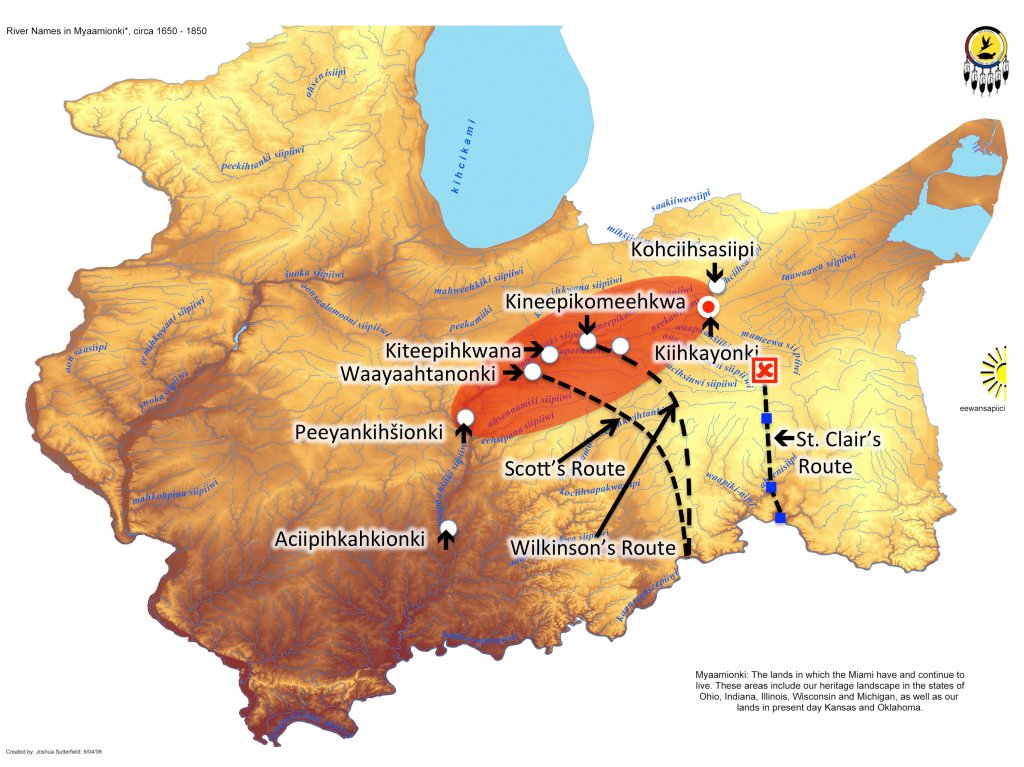

At the end of May, scouts alerted the villages that a mounted force of Mihši-maalhsa had moved north from the Kaanseenseepiiwi (Ohio River) and was crossing the White River. The allied villagers grouped their forces together at the headwaters of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi and waited for the Mihši-maalhsa. Their wait turned out to be in vain. In mid-June, reports reached the Taawaawa Siipiiwi that the mounted Mihši-maalhsa had attacked the Waayaahtanonki (Wea) area of the middle Wabash (see Map 1 below). The attack destroyed five villages including two Waayaahtanwa (Wea) villages, two Kickapoo villages, and the Myaamia village of Kiteepihkwana (Tippecanoe). The Mihši-maalhsa killed thirty-eight and captured fifty-seven residents, mostly women and children.[4] The Waayaahtanonki area villages were mostly undefended because nearly all the men of arms bearing age were gathered at the Taawaawa Siipiiwi awaiting the very attack that hit their homes and took their families captive. These men immediately returned home and found their villages in ashes and their families gone. They also found the body of Keekaanwikania, a well-liked village war leader. The Mihši-maalhsa killed Keekaanwikania in their attack on the first village and defiled his body so that he was hardly recognizable.[5] Disturbing violence like this was tragically common practice used by both the Mihši-maalhsa and the men of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi and Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi to send messages to their enemies.

The Mihši-maalhsa commander of the attack on the Waayaahtanonki area villages, General Charles Scott, released a few captives with a message for their relatives. The Kentuckian spelled out the terms by which the villagers could reclaim their captive families. They were required to go to Fort Washington by the beginning of July, “bury the hatchet,” and agree to peace. Then, and only then, their families would be returned, and their communities would be allowed to live in peace under the protection of the United States. Scott’s message concluded with a bald threat: “should you foolishly persist in your warfare, the sons of war will be let loose against you, and the hatchet will never be buried until your country is desolated, and your people humbled to the dust.”[6]

Some of the Waayaahtanwa went to Fort Washington as demanded. Upon arrival, the commander of the fort rudely informed them that the terms of their relatives’ release had changed. In the eyes of the Mihši-maalhsa, they were misbehaving children, and therefore there would be no peace until all the peoples of the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi and Taawaawa Siipiiwi put down their arms and accepted the protection of the United States. Additionally, the U.S. Army forced some of the captives to serve as guides and interpreters in the coming invasion.[7]

Throughout June and July, British agents tried to council the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villages to seek a peace settlement with the United States.[8] Some of the allied villagers wanted to entertain negotiations, but other members of the alliance believed that the Mihši-maalhsa could not be trusted. Joseph Brant, a Mohawk leader, reported to the British that the Myaamia and the Shawnee were the most resistant to any kind of settlement. They believed that there could be no reasonable terms for peace from a group they perceived as “so wicked.”[9]

In early August, the Shawnee and Myaamia likely felt justified in their resistance when they received word of another force of mounted Mihši-maalhsa moving north from the Kaanseenseepiiwi. The men of Taawaawa Siipiiwi and their allies proceeded to gather once again to defend their homes against the invading force. Sometime after August 7, word reached the Taawaawa Siipiiwi that the Mihši-maalhsa had once again turned west and attacked a largely undefended village. This time the village of Kineepikwameekwa (Eel River) was targeted. The majority of the Kineepikwameekwa men were gathered on the Taawaawa Siipiiwi, but they quickly left to ascertain the damage to their homes and check on the welfare of their families. They arrived to find that six of their relatives had been killed in the attack and that thirty-four women and children had been taken captive. Their village was in ashes and their cornfields, only just entering the green corn stage, were cut down and burned. They also discovered that the Mihši-maalhsa returned to the Waayaahtanonki area towns and destroyed any remaining corn that Scott’s invasion missed.[10] This attack made it clear to all the peoples of Taawaawa Siipiiwi that the Mihši-maalhsa peace overtures bordered on the duplicitous.

The overall commander of the Mihši-maalhsa forces, Major General Arthur St. Clair, ordered the attack on the Kineepikwameekwa village to keep the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villagers off balance while the U.S. Army prepared a much larger invasion. This larger invasion was running months behind schedule, and St. Clair was under pressure from his superiors and the general public to do something. St. Clair was having extreme difficulty gathering together the required manpower and the supplies vital to an army’s operation: food, arms, horses, uniforms, etc. This logistical traffic jam led St. Clair to order James Wilkinson, a lieutenant colonel in the Kentucky militia, to attack Kineepikwameekwa. Wilkinson’s attack was successful in achieving the short-term goals of destroying another village and killing or capturing as many enemy combatants as possible. The attack was less successful at distracting or off balancing the Taawaawa Siipiiwi alliance. Instead, the attack strengthened the belief that the only practical choice was to militarily resist the Mihši-maalhsa invasion of their homelands. Wilkinson’s invasion made it clear to everyone there would in fact “be no peace” until either the Mihši-maalhsa or the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villages were “humbled to the dust.”

At some point in early September, scouts reported to that a large force of Mihši-maalhsa had marched from Fort Washington and had encamped about thirty miles to the north on the Ahsenisiipi (Great Miami River). Shortly after, the soldiers began to construct a fort. Scouts from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villages kept a constant watch on this invading army. Scott and Wilkinson’s attacks had taught the valuable lesson that on-the-ground intelligence would help them defend their villages better than assumption and anticipation.

These scouts continued to follow the Mihši-maalhsa army as they moved extremely slowly northward. The army followed an established trail that people had used for generations, but they were forced to expand the trail to accommodate the passage of wagons and cannon. This forced the army to essentially blaze a brand new road through the forests. It was time consuming and frustrating work. Over a month later in early October, the Mihši-maalhsa stopped to build another fort approximately six miles south of the eventual site of Greenville, Ohio. Near the end of October, the Mihši-maalhsa remained encamped at this second fort.

Around the same time, the men of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi alliance moved south to attack the Mihši-maalhsa before they reached the Taawaawa Siipiiwi or before they could change direction and attack more undefended villages. The British reported that over 1,000 men moved south out of Kiihkayonki. Their forces included men from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villages: Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, Wyandot, and Myaamia. They also included allies not from the valley: northern Ottawa, Ojibwa, Potawatomi, Seneca, Mohawk, and Cherokee. The army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi moved south with the belief, gained from captives and deserters, that the Mihši-maalhsa outnumbered them at least two to one.[11]

The war leaders from these various groups likely met in council to agree to a plan of action. It also seems likely that the Myaamia women’s councils had the time and opportunity to meet. They likely played a role in the decision to engage the Mihši-maalhsa before their homes and agricultural fields were in danger. It seems, based on their behavior, that their collective plan was to ambush the Mihši-maalhsa somewhere in the denser forests approximately fifty miles south of Kiihkayonki. Shortly after leaving Kiihkayonki, the army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi divided into smaller units of twenty to thirty men. This was a mode of travel that was culturally familiar as it was the typical size of a war party. These small units were more flexible than a large force and they were easier to provision with food. Within days, the army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi gathered together in larger camps on the northern banks of the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi.

Increased numbers of scouts continued to observe the Mihši-maalhsa army as it inched along. In early November, the Mihši-maalhsa reached the banks of the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi, near what is today the town of Ft. Recovery, Ohio. The leaders of the army mistakenly believed that they were encamping on the Nameewa Siipiiwi (St. Marys River) and thought they were within a day’s march of Kiihkayonki. It remains a mystery whether this mistake was the result of their captive guides leading them astray or was an honest misunderstanding. On November 3, the Mihši-maalhsa set up camp on the southeast bank of the river on a small flat rise surrounded by low wooded wetlands on three sides and the river on the fourth. Scouts observed the position of the invading army closely as the evening drew into night.

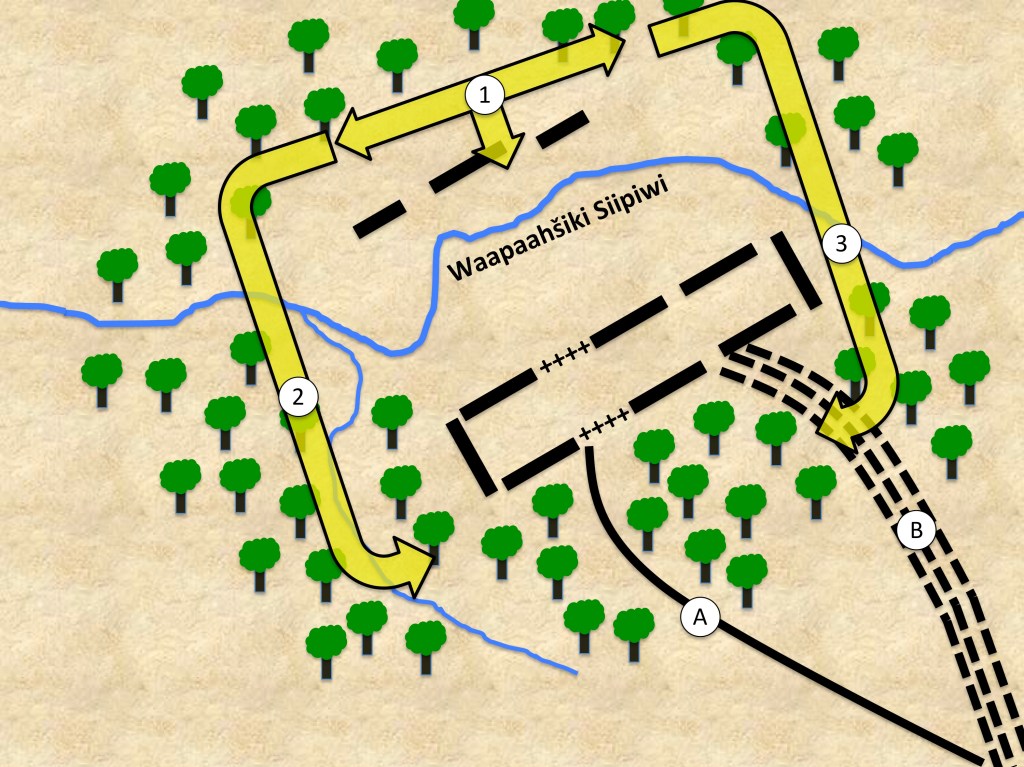

The Mihši-maalhsa encamped in a rectangular formation with the long sides running roughly northeast to southwest and the short sides running roughly northwest to southeast (see Map 2 below). The Mihši-maalhsa placed their cannons near the center of both lines. Half these cannon overlooked the river, and half faced southeast looking out over the swampy lowland below. The Mihši-maalhsa forces were slightly too large for the selected area and so a few hundred militia crossed the river to set up an isolated camp on the northwestern bank. Neither camp fortified their position with wooden log barriers, called breastworks, or earthen barriers. As the camp quieted for the night, scouting parties from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi continued to move around the camp assessing its weaknesses.

A few hours before dawn, the army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi must have held at least a brief war council that included war leaders from all the communities. We can be fairly sure this occurred because the attack that followed was clearly the product of a thought out and coordinated plan. We do not know the names of all the war leaders who participated in this council, but we do know that likely participants were: Mihšihkinaahkwa (Little Turtle) and Eepiihkaanita (William Wells) of the Myaamia; Blue Jacket of the Shawnee; Buckongahelas of the Delaware; Tarhe of the Wyandot; and Egushawa of the Ottawa. Many other voices were probably a part of this council of war, but the record does not provide us with more names.

The council’s plan was to advance on the Mihši-maalhsa camp shortly before sunrise that coming morning. The army would form a semicircle with the Wyandots and Haudenosaunee (Seneca and Mohawk) positioned on the right. The Delaware, Shawnee, and Myaamia would occupy the center, and the Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Potawatomi would occupy the left of the formation. Remaining groups must have been divided up among these three positions. The plan was to engage the Mihši-maalhsa in a surprise attack at dawn and as quickly as possible wrap around the larger camp and surround it before the Mihši-maalhsa could organize. Once the fighting began, individual war leaders would provide direction as needed, but for the most part the group could count on individuals carrying out the attack without much additional guidance. The only specific tactical instructions were given to a small unit of Myaamia and perhaps a few similar units among other communities. These groups were tasked with targeting the crews operating the cannon. Their goal was to take the cannon out of the battle before they could be effectively used to defend the Mihši-maalhsa camp. In the case of the Myaamia, this assignment was given to a group under leadership of Eepiihkaanita (William Wells).

Once the plan was agreed to, the communities organized themselves as described and advanced on the Mihši-maalhsa. Just as the sun was beginning to peek over the horizon, the Delaware, Shawnee, and Myaamia hit the isolated camp on the northwestern bank of the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi. The first volley of gunfire took the camp completely by surprise. Within minutes the entire camp was overrun. The survivors fled in a disorganized fashion across the river and immediately spread chaos within the larger camp.

The right and left wings of the army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi quickly moved into position on the edges of the camp while the Mihši-maalhsa were focused on the Delaware, Shawnee, and Myaamia attacking the center. The Wyandot, Haudenosaunee, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Potawatomi moved mostly unobserved through the forested bottomland. Once in position, they too began to pour musket fire into the Mihši-maalhsa camp.

Within a few short minutes, the army of Taawaawa Siipiiwi had completely surrounded the camp. From their positions behind trees, they could fire up into the Mihši-maalhsa without exposing themselves to return fire. They also quickly noticed that their enemy was not taking into account the slight change in elevation between the camp and forested areas. Most of the Mihši-maalhsa fire, both from muskets and cannon, was going into the treetops. In some cases, the fire was hitting tree limbs thirty feet over the heads of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi men.[12]

Over the next three hours of fighting, the men of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi skillfully avoided Mihši-maalhsa bayonet charges and then surrounded these smaller forces. Isolated from the camp, these groups of Mihši-maalhsa were then forced to fight their way back into their own camp or risk being overrun. At the same time, others took advantage of the defensive gaps left by each charge and moved behind their enemy’s defensive lines into the middle of the camp. Once within the camp, they attacked and killed soldiers and noncombatants, which included men, women, and children. Their goal was to either utterly annihilate the Mihši-maalhsa army in place, or destroy the integrity of the army by sending them into disorganized retreat. Taking large numbers of captives was not their objective and at that point in the battle was not even possible. Every time the men of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi entered the camp, the Mihši-maalhsa eventually organized a charge and pushed them out. But these breaks in the line took a heavy toll. By the end of the third hour of fighting, the men of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi could see that the Mihši-maalhsa were near the point of total collapse.

Ammunition was running low on both sides, and some of the men from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi began to fire arrows into the center of the Mihši-maalhsa camp, where most of their enemy was massed. The Wyandot, Haudenosaunee, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Potawatomi on the southeastern side of the encirclement successfully blocked access to the road, and for a moment it seemed that they might in fact destroy the entire army of the Mihši-maalhsa.

Shortly after the sun broke free of the treetops, the muted sounds of drums could be heard from within the camp. Soon thereafter, a large mass of Mihši-maalhsa broke through the encirclement to the north of the road. Hundreds of Mihši-maalhsa joined the disorganized run following the breakout through wooded swampland. The remains of the Mihši-maalhsa army ran in a long line parallel with the road. After moving some distance away from the trap, they found the road they had cut through the trees and continued their uncontrolled flight south. The army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi ceased their pursuit after four or five miles. They no longer needed to chase the disorganized rabble. They knew that they had destroyed the army of the Mihši-maalhsa on the banks of the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi.

The commander of the Mihši-maalhsa, General Arthur St. Clair, was thrown unceremoniously over the back of a packhorse so that he too could participate in the disorganized flight. St. Clair suffered from the disease gout, which affected his ability to walk, and was therefore forced to become baggage in order to escape the collapse of his army. The flight continued for nearly thirty miles back to the fort the Mihši-maalhsa completed in late October. This fort, which had been named Fort Jefferson in honor of the Secretary of State, provided only temporary security. It was too small to house all of the survivors of the battle. Some military stability was restored when three hundred men of the First United States Regiment returned from chasing deserters and protecting the supply line. Their return, however, only made the supply situation more desperate. Fort Jefferson also lacked enough food or medicine for the nearly three hundred injured. In truly tragic fashion, nearly all the survivors of the battle, injured or not, had to continue their march seventy miles south to Fort Washington on the banks of the Kaanseenseepiiwi (Ohio River).

The army of Taawaawa Siipiiwi was ecstatic over what they believed was a crushing victory. They celebrated because they had stopped the invading army in a dramatic manner. They accomplished this without sacrificing their villages or their farm fields along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi. They did lose twenty-one men and had another forty wounded. These losses would be mourned in their home villages and no feelings of victory would fill the holes left behind in the families of these men. But the families of the fallen would still have their homes and the fruits of their agricultural labors over the coming winter.

The army of Taawaawa Siipiiwi celebrated as the early afternoon sun shone down on the wreckage of St. Clair’s camp and the bodies of the Mihši-maalhsa. Some of these bodies had their mouths filled with earth from the battlefield. The message was intended to be clear across the cultural divide: “This is the only way you are getting our land.” The men from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi and their allies had been fighting against this enemy for over thirteen years and the utter hostility they felt towards the Mihši-maalhsa cannot be understated.[13]

Among the peoples of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi and their allies there were established cultural practices around warfare that can be difficult to comprehend from our vantage point today. The defilement of the dead was a practice that was used by all sides of this conflict to vent rage, stoke fear, send messages, and damage an enemy’s existence in the afterlife. Over the decade and a half of warfare along the Kaanseenseepiiwi, a subculture of vengeance and reprisals drove these kinds of displays to levels not seen since the Fur Trade Wars of the 1600s.

Similarly, it is difficult for us to understand the widespread practice of executing wounded prisoners and prisoners unsuitable for adoption. This practice violates our contemporary understandings of the informal and formal codes that many nations follow in warfare. But we must always remember that today’s rules were not in force two hundred years ago. At that time, it was understood that the life of a captive taken in battle was forfeit. Only a small handful of captives were taken back to a captor’s village, and even then one’s life was not guaranteed. Some captives were adopted, some put to work as forced labor, and some the community ritually executed to vent collective grief and appease the spirits of relatives who died in battle.

It is difficult to fully understand our ancestors’ actions in the context of their times, but it is important that we make the attempt. It is equally important that we resist the use of terms like “massacre” and “savagery.” The Mihši-maalhsa used these terms as ammunition in a war of words to convince their own people to continue a war that many were beginning to question. They used these words without acknowledging that Americans were also allowing vengeance and hatred to shape the violence they perpetrated during this war.

The men of the army of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi believed that they had turned General Scott’s own words against him and “humbled” their enemy “to the dust.” No village or collection of villages could afford to lose nearly seven hundred men in one day, nor deal with three hundred incapacitated by injury. In fact, losses of this magnitude would have destroyed the integrity of their communities. It is easy to see why they believed that this victory could mean that the Mihši-maalhsa would have to seek peace.

This battle – mikaalitioni waapaahšiki siipionki (the Battle of the Wabash) – remains one of the largest defeats ever suffered by the United States Army. Out of the 1,450 who awoke that morning of November 4, around eight hundred escaped with their lives. The casualty rate, which includes those killed (648) and injured (279), was an appalling 64%. The sorrow emanating from these losses would reverberate among hundreds of families living in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and beyond.[14]

The Battle of the Wabash was a humbling experience for the men and women who survived. Some were never able to shake the horror of that battle from their minds, and the American record list them as “deranged.” The government of the United States found the defeat to be humiliating, but the cruel reality was that the loss could be sustained. The United States could afford to sacrifice St. Clair’s army on the altar of arrogance and disorganization and yet survive. In 1790, the population of the young country was nearly four million. Over the following ten years, it would increase in size by another million. Sadly, the lives of seven hundred men were a sustainable sacrifice. The leaders of the young nation believed land acquisition was necessary for their “Empire of Liberty” to thrive. With more money, time, and effort the government could, and would, assemble another army of young men to send north to the Taawaawa Siipiiwi.

It is this shocking reality that came to inform Myaamia responses to third invasion of our homelands led by General Anthony Wayne. Between 1791 and 1794, it became apparent to some Myaamia leaders that they could kill hundreds, or perhaps even thousands, of Mihši-maalhsa and the next summer another army would march on their villages. If military victory would not produce peace, then another course of action would have to found.

In part four of this series (linked here), we examine the attempts to clear a new path of peace for those living along the Kaanseenseepiiwi, Taawaawa Siipiiwi, and Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi. We then turn to examining the Battle of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi (Fallen Timbers) and its aftermath from a Myaamia point of view.

If you would like to comment on this story, ask general historical questions, or request a future article on a different topic, then please make a comment below. Our history belongs to all of us and I hope we can use this blog as one place to further our knowledge and or strengthen connections to our shared past. You can also email George at ironstgm@miamioh.edu.

Notes

[1] McKee’s letter dated July 5, 1791 in Clarence M. Burton, ed. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections, Vol. 24 (Lansing, MI: Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, 1895), 280.

[2] Wiley Sword, President Washington’s Indian War: the Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 141.

[3] Untitled journal in Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections, Vol. 24, 251.

[4] Sword, President Washington’s Indian War, 139-41.

[5] Letter to McKee in Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections, Vol. 24, 273-74.

[6] American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, Vol. 4, Indian Affairs, no. 1 (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832), 133.

[7] Sword, President Washington’s Indian War, 142. McKee to Johnson, November 1, 1791, in Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections, Vol. 24, 330-31.

[8] McKee’s “Speech to… Nations… at the Foot of the Miamis Rapids” in E. A. Cruikshank, ed, The Correspondence of Lieut. Governor John Graves Simcoe, with Allied Documents Relating to His Administration of the Government of Upper Canada, Vol. I, 1789-1793 (Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1923), 36.

[9] Sword, President Washington’s Indian War, 142

[10] Helen Hornbeck Tanner and Miklos Pinther, Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (Civilization of the American Indian series; v. 174. 1st ed. Norman: Published for the Newberry Library by the University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 73. Harvey Lewis Carter, The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 101. Sword, President Washington’s Indian War, 156.

[11] “Declaration of John Wade, Deserter From American Army” in Michigan Pioneer and Historical Collections, Vol. 24, 328.

[12] Sword, President Washington’s Indian War, 176, 179.

[13] Sword, President Washington’s Indian War,84.

[14] Carter, Life and Times of Little Turtle, 108.

Leave a comment