aweentioni weešihtooyankwi

myaamiaki neehi eeweemakinciki mihši-maalhsaki

We Make Peace

The Myaamia and Our American Relatives (Part I)

In this post, we examine our people’s first treaty with the Mihši-maalhsa – the Treaty of Greenville. While researching this article I relied heavily on Andrew Cayton’s “’Noble Actors’ upon ‘the Theatre of Honour’: Power and Civility in the Treaty of Greenville,” in Contact Points: American Frontiers from the Mohawk Valley to the Mississippi, 1750-1830. Much to my great sorrow, Dr. Cayton passed away in December of 2015. As one of my advisors in my M.A. program, he had an immeasurable impact on my development as an historian. He was a great scholar, teacher, mentor, and a gentle and kind man. He will be missed. kweehsitawaki oonaana neepwaankia.

This post also draws on Harvey Lewis Carter’s The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash; and James Buss’s Winning the West with Words: Language and Conquest in the Lower Great Lakes. I highly recommend all of these works if you’re interested in learning more about this period of our history and the intricacies of treaty negotiations in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In our last post we looked at mikaalitioni taawaawa siipionki (the battle on the Maumee River). This battle, also known as Fallen Timbers, marked the military defeat of the alliance of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi villages. This alliance included Myaamia, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa, and Wyandot peoples who lived along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi or nearby as well as their Potawatomi and Ojibwe allies who came from northern villages. Following the battle, each of these villages had to make difficult choices. Some communities sought out the Mihši-maalhsa (Americans) and took the first steps towards peace. Some left the region and moved north or west rather than negotiate. Finally, a few communities tried one last time to convince the British to support their continued resistance against the Americans. However, by the spring of 1795, the majority of these communities agreed to attend a peace negotiation with the United States, which would occur near Ft. Greenville in the summer of that year.

The First Steps Towards Peace

The battle on the Taawaawa Siipiiwi (Maumee River) left the Myaamia and their allies in dire straits.[1] The military defeat and the inaction of the British left many of these communities demoralized. Furthering this sense of powerlessness was their continued inability to protect their homes and fields. After the battle, the Mihši-maalhsa spent the fall burning all the villages along the Taawaawa Siipiiwi and their stored agricultural produce.[2] They also consolidated their military strength by building yet another new fort. This new fort, named Fort Wayne in honor of the Mihši-maalhsa commander, stood near the headwaters of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi directly across the river from Kiihkayonki, the largest and most influential Myaamia village at that time. For at least the third time in five years, the allied villages faced another winter with no shelter and little to no food.

This battle and its aftermath produced a massive change in Myaamia attitudes and actions regarding the Mihši-maalhsa. When the war with the Mihši-maalhsa began, Myaamia villages were some of the strongest supporters of violent resistance and refused all calls to negotiate. After the resounding victory at the Battle of the Wabash in 1791, a few Myaamia leaders began to push for peace but most of their communities disagreed. Following this third battle, a serious debate erupted within Myaamia villages over what course of action to pursue. For the first time, larger numbers of Myaamia people pushed their leaders to consider peace.

Late in the fall of 1794 or early in the winter of 1795, Šimaakanehsia, a leader from the Kineepikwameekwa Siipiiwi village (Eel River), met with the Mihši-maalhsa and officially “took them by the hand.” At that time, to “take someone by the hand” was a metaphor that indicated an interest in negotiating, being friendly, and seeking peace. It is likely that Šimaakanehsia presented General Wayne with a symbolic gift that represented their peaceful intentions and it is equally possible that Wayne presented one in return. Negotiating peace usually required mutual gift giving. Following this initial agreement, most of the Myaamia villages south and west of the Kineepikwameekwa Siipiiwi were seen as officially at peace with the United States. Opinions remained divided upstream from that village and over the rest of the winter debate continued. For generations, the family of Šimaakanehsia preserved a flag with General Wayne’s name embroidered across the top. Wayne presented this flag to Šimaakanehsia in the summer of 1795, likely in recognition of Šimaakanehsia’s efforts at establishing an early peace.

Over the winter of 1794-95, Myaamia leaders took two additional important steps. First, two war leaders arrived at Fort Wayne in December of 1794 and gave assurances that representatives of their nation would soon head to Greenville to negotiate a preliminary peace with General Wayne. It is quite likely that one of these war leaders was Mihšihkinaahkwa, since he had begun to push for peace prior to the Battle of the Taawaawa Siipiiwi. As promised, Pinšiwa (Jean Baptiste Richardville), Kiilhswa, and Kakockapackeshaw* arrived at Greenville in January and negotiated directly with Wayne. Together they agreed to a general peace and a few preliminary articles. One of these articles accepted the terms of the Treaty of Fort Harmar as the basis of the coming peace treaty. This point would turn out to be quite controversial the following summer. Myaamia leaders agreed to return the next summer to negotiate a formal peace treaty, and they asked that the treaty be held where the war fire was first kindled: Kiihkayonki (Ft. Wayne), where the Myaamia would serve as the host and perhaps gain an advantage in the negotiations.[3] Instead, General Wayne planned to hold the summer peace conference at Greenville, where the Americans would serve as hosts.[4]

The second important move made over that winter involved convincing anti-American Myaamia leaders that the British were unlikely to help their communities in any continued efforts at military resistance. The strongest voices against peace with the Americans were Pakaana and Le Gris. Both men were civil leaders from the Kiihkayonki area and both had suffered great losses at the hands of the Mihši-maalhsa. Over the winter, Pakaana was taken to Detroit by Mihšihkinaahkwa to see firsthand that the British were not going to offer help against the Mihši-maalhsa. The following spring both Pakaana and Le Gris agreed that peace with the Mihši-maalhsa was the only option available to Myaamia people.[5]

*This name (Kakockapackeshaw) is recorded legibly in the historical record, but its meaning and shape in Myaamiaataweenki (the Miami language) cannot be discerned.

The Treaty of Greenville June 16 – August 12, 1795

Over the first weeks of June, representatives from many communities began arriving in small groups at Fort Greenville for the coming treaty negotiation. By the middle of June, representatives from the Delaware, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and from the Myaamia village on the Kineepikwameekwa Siipiiwi were all present and General Wayne felt it was necessary to officially welcome the early arrivals to Greenville.

General Anthony Wayne officially opened the peace negotiation on June 16 with the lighting of a new council fire. By lighting this fire at Greenville, Wayne was using tribal symbols and cultures in an attempt to draw former enemies into a new alliance. This fire would burn farther away from the British, and Wayne planned that this fire would be tended by the Mihši-maalhsa. If successful, this would make the Fifteen Fires – the fifteen states of the United States – the center of this new alliance, and displace the British, Shawnee, Delaware, and Myaamia from the roles at the center of the previous alliance. At the same time, Wayne’s hopes for an influential future were tempered by his concerns over the capabilities and political youth of his nation. The historian Andrew Cayton has successfully argued, “American officers at Greenville were obsessed with what the Indians thought of them.” It was not enough to conquer land by force; they wanted tribal communities to accept the legitimacy of the U.S. government and its rights to any territories ceded at the Treaty of Greenville.[6]

After lighting the council fire, Wayne presented the calumet of peace, a highly decorated tobacco pipe, to all those present. Smoking the pipe symbolized the joining of hearts and minds in the pursuit of peace (see the image below). After everyone had smoked the calumet, Wayne opened by stating “I take you all by the hand as brothers, assembled for the good work of peace… I have cleared this ground of all brush and rubbish, and opened roads to the east, to the west, to the north, and to the south, that all nations may come in safely and ease to meet me.” Wayne’s words were shaped by the diplomatic protocols and language of the tribal leaders gathered at Greenville. By using this language, he demonstrated his respect for ages old tribal conceptions of how peace was created.

General Wayne’s use of the term “brothers” to refer to his guests was intentional and also a reference to collective tribal diplomacy. For Myaamia people kinship and peaceful alliance were closely related concepts. For example, the terms eeweemilaani (you are my relative), eeweenkiaani (I am thankful), and aweentioni (peace) are all formed from the same verb stem aweem-. Similar concepts and beliefs were shared among most of the groups gathered at Greenville. Conceptually, for leaders of that period, to be at peace was also to be related, as an ally, and to be thankful. By using the term “brothers,” Wayne was seeking to transform former enemies into kin. The use of Algonquian and Iroquoian kinship language would become increasingly important throughout the negotiations leading up to a significant reorganization of the alliance of family on the last day of the council.

To close out this first meeting, General Wayne symbolically covered the council fire to “keep it alive, until the remainder of the different tribes assemble, and form a full meeting and representation.” He gave each group “a string of white wampum,” another symbol of peace, and proclaimed again that “the roads are open” and that they would “rest in peace and love, and wait the arrival of our brothers.”

Throughout the rest of the two months of negotiation, General Wayne continued to demonstrate a certain level of respect for tribal protocols and traditions. However, Wayne would make some key mistakes in the early days of the full council. Of most concern would be his failure to repeat his initial message of peace to the entire gathered council, which would not be fully assembled until a month later. In collective tribal diplomacy, repetition was a sign of dedication to an ideal. Key concepts were often repeated using different artful metaphors so that they grabbed the audience’s attention. Wayne’s failure to constantly repeat his desires for peace caused some attendees to worry about the Mihši-maalhsa’s true intent at Greenville.

The rest of the Myaamia delegation arrived on June 23, seven days after the lighting of the council fire. The delegation included people from various villages including Kiihkayonki, Kineepikwameekwa Siipiiwi (Eel River), Waayaahtanonki (Wea), and at least one of the Peeyankihšia (Piankashaw) villages. Le Gris and Mihšihkinaahkwa headed the delegation. It also included Pinšiwa, Cochkepoghtogh*, and Waapimaankwa, and at least 12 additional unnamed Myaamia people. Le Gris greeted Wayne and acknowledged, “that he was very happy to see the General.” He concluded by adding “that the Miamies were united with him in friendly sentiments and wishes for peace.”[7]

On the next day, tensions flared briefly when an explosion tore through the armory inside Fort Greenville. In the aftermath, the Mihši-maalhsa pulled inside the fort and took up defensive positions. The Myaamia embassy and their relatives from the Taawaawa Siipiiwi alliance, fearing treachery, fled into the woods. They remained hidden until it was made clear that the explosion was an accident and the Mihši-maalhsa did not intend to do them harm. The accident made clear what the polite words spoken during introductions had not; this peace was still fragile and trust between the former enemies did not yet run deep or wide.[8]

Calm was restored over the following day and those gathered agreed to wait to reopen the treaty negotiations until the rest of their “brothers” had arrived. On June 26, a group of thirty-four Ojibwe and Potawatomi arrived at Fort Greenville, and the Wyandot of Sandusky arrived on July 12. At that point, the only major groups absent from the gathering were the Wyandot of Detroit and the Shawnee. On July 15, the entire group agreed to reopen the treaty council despite the continued absence of those communities.[9]

Major General Anthony Wayne opened the full council of the Treaty of Greenville with an official swearing in of the interpreters for the negotiation. This was not a common practice among the tribal communities at Greenville. It was a sign of Mihši-maalhsa worries over control of communication. The Mihši-maalhsa desired to create peace and acquire legal title to land through words: both spoken and written. For the Mihši-maalhsa the act of translation would be essential to asserting their peaceful authority, but they were vulnerable because most Mihši-maalhsa officers knew little to nothing of the eleven languages spoken by the various tribal communities attending Greenville. Following the official swearing in, Wayne then turned to the gathered leaders and addressed them “Younger brothers: These interpreters whom you have now seen sworn, have called the Great Spirit to witness, that they will faithfully interpret all the speeches made by me to you, and by you to me; and the Great Spirit will punish them severely hereafter, if they do not religiously fulfill their sacred promise.”[10]

It is important to note that Wayne’s concern with language and translation preceded all other speeches, even those most central to peace from the tribal communities’ perspectives. Given Wayne’s concerns, it is even more interesting to note that Eepiihkaanita, known as William Wells to the Mihši-maalhsa, was one of these sworn translators. Throughout the entire treaty negotiation, Eepiihkaanita served as the translator for the Myaamia, including his father-in-law Mihšihkinaahkwa who would go toe to toe with General Wayne over the course of two weeks of debate and negotiation. Mihšihkinaahkwa’s achievements at the Treaty of Greenville on behalf of his people were due in no small part to Eepiihkaanita’s skills as a translator.[11]

Following the swearing in of the translators, Wayne presented the “calumet of peace of the Fifteen Fires of the United States of America.” As before, Wayne presented the decorated pipe as a symbol respect to old tribal protocols that joined the hearts and minds of all attendees as they began to discuss peace in earnest. Wayne first passed the pipe to Šimaakanehsia, the Myaamia leader from the Kineepikwameekwa Siipiiwi village (Eel River). Šimaakanehsia was the first of the alliance’s leaders seek out peace with the United States, and so he and the broader Myaamia community were accorded a place of honor at the opening of the negotiation.[12]

After completing the opening rituals, Wayne reminded the council of the importance of treaties, which “made by all nations on this earth ought to be held sacred and binding between the contracting parties.” He then laid out how past treaties were recorded in written form in order to maintain the sacred bonds created by the various nations. He then introduced the preliminary articles of the treaty, which most of the communities had agreed to the previous winter.[13] The Mihši-maalhsa wanted the land sessions made in the Treaty of Fort Harmar (1789) to be the foundation of the Treaty of Greenville. However, the Myaamia and the Shawnee as well as other groups fiercely disputed the former treaty. In an attempt to avoid this controversy, Wayne quoted the Wyandot from the fall of 1794, who he claimed told him that the Treaty of Fort Harmar “appeared to be founded upon principles of equity and justice, and to be perfectly satisfactory to all parties at that time.” Wayne added that it was the Wyandot who proposed “that treaty, as a foundation for a lasting treaty of peace between the United States and all your nations of Indians.” Through this brilliant strategy, Wayne tried to use the voices of the Wyandot, senior members of the alliance, to assert the legitimacy of a treaty that most leaders saw as a sham agreement achieved through coercion and duplicity.[14] Before any of the other leaders had a chance to reply, Wayne closed out that day’s council with the recommendation that everyone “appropriate two or three days to revolve, coolly and attentively, these matters, and those which will naturally follow them.” The council then adjourned with an agreement to pick up again on the 18th.[15]

After two days of rest and reflection, the council reopened with a short but clearly oppositional speech by the Myaamia leader Mihšihkinaahkwa. He began by recognizing General Wayne as his “brother,” but then proceeded to challenge Wayne to clearly state that their goal at Greenville was to achieve peace. During the first day of the conference Wayne did not use the word “peace” a single time, but instead spoke about translation, the sanctity of treaties, and the lands the Mihši-maalhsa desired. Mihšihkinaahkwa’s criticism was intended to remind Wayne that from a Myaamia point of view, the council must first establish peace before negotiating any other point. Mihšihkinaahkwa concluded by denying the legitimacy of the Treaty of Fort Harmar. He and other Myaamia leaders were “entirely ignorant of what was done at that treaty.” Mihšihkinaahkwa’s matter-of-fact denial of the Fort Harmar treaty must have surprised General Wayne, at least a little. After all, Myaamia representatives had approved these exact treaty articles the previous January.[16]

Mihšihkinaahkwa’s opening speech at Greenville is interesting for multiple reasons. First, it is significant that the Myaamia were the first to speak. Myaamia communities were neither the largest nor the most influential among the tribal peoples gathered at Greenville. Culturally, it was also normal to allow elder members of the alliance, Wyandot, Delaware, or Shawnee, to speak first. Additionally, within his home community, Mihšihkinaahkwa was previously a neenawihtoowa (war leader) and peace councils were usually the responsibility of an akima (civil leader), like Le Gris. The record does not indicate how the Myaamia came to speak first or how a war leader came to serve as the main Myaamia speaker. It is possible that because the Myaamia did not attend the Treaty of Fort Harmar they were best positioned to refute it. It is equally possible that his community considered Mihšihkinaahkwa to be a skilled public speaker and so his selection as council spokesperson might have been pragmatic. It is also likely that his family ties to their assigned translator, Eepiihkaanita (William Wells), contributed to his selection.[17]

The Ojibwe leader Mashipinashiwish echoed Mihšihkinaahkwa’s challenge to General Wayne regarding the treaty. In response, a Wyandot leader, Tarhe, argued that he did not think it proper “to select any particular nation to speak for the whole.” Tarhe was one of the signers of the Treaty of Fort Harmar and he must have felt that Mihšihkinaahkwa and Mashipinashiwish were directly attacking him. He asked Wayne to appoint a specific day for each group to speak and to delay a few days before continuing the council. Clearly the fraudulent treaties of the 1780s were a cause of major disagreement. For peace to proceed at Greenville, those treaties would have to be addressed. Before adjourning the council, Wayne responded that he would “endeavor to fully explain the treaty of Muskingum (Fort Harmar)…” and he added that he hoped “we will have all things perfectly understood and explained, to our mutual satisfaction, before we part.”[18]

That evening, Blue Jacket with thirteen Shawnee and Masass with twenty Ojibwe all arrived at Greenville. Masass greeted Wayne and explained that they had been detained by Joseph Brandt’s efforts to keep them from negotiating with the Americans. Blue Jacket admitted that he still intended to follow through on his promise of peace from the previous winter but his people were divided and many did not want to negotiate. He told Wayne “you must not be discouraged” but that a great number of Shawnee would not come to Greenville, though “his nation will be well represented.”[19]

On July 20th, General Wayne renewed the council and opened with a direct response to Mihšihkinaahkwa’s first request regarding peace. Wayne complained, “I did hope and expect, that every man among you would be perfectly acquainted with my sentiments on this subject.” Wayne pointed to the many messages of peace he personally sent out prior to the council. He then quoted his discussion with the Wyandot from the previous winter: “I told them that peace was like that glorious sun which diffused joy, health, and happiness, to all the nations of this earth, who had wisdom to embrace it, and that I, therefore, in behalf of and in the name of the President of the United States of America, took them all by the hand, with that strong hold of friendship, which time could never break.” He then presented Mihšihkinaahkwa and Mashipinashiwish with strings of wampum, “which are not purer or whiter than the heart that gives them.”[20]

Having correctly established peaceful intent, from a Myaamia point of view, the council could then turn to negotiation of the terms of peace. Mihšihkinaahkwa immediately addressed the Treaty of Fort Harmar arguing, “We Miamies and Wabash tribes are totally unacquainted with it.” Mihšihkinaahkwa was arguing that it could not be the foundation for the peace they were negotiating at Greenville. In response, General Wayne read aloud the entire text of the disputed treaty. He concluded by reminding the council that many of the leaders who signed the treaty were present at Greenville and that if they were willing to be honest, they could “inform you of everything relating” to the treaty “and give full satisfaction on the subject.” In conclusion, Wayne made his desires clear, he wanted the boundaries established at Ft. Harmar to be the basis of the current treaty. Wayne was trying to ram the terms of the Treaty of Ft. Harmar down the throats of the entire council, whether they had signed the 1789 agreement or not. This debate would become the center point of Mihšihkinaahkwa’s war of words with Wayne over the following days.[21]

On July 21st, the entire day was filled with discussion of the disputed treaty. Masass, an Ojibwe leader, opened by declaring that they had bad interpreters at Fort Harmar and they did not understand that they were agreeing to cede land to the United States in exchange for gifts. In response, the Wyandot asserted that Masass’s claims alarmed them and they wished to address them directly, but asked for time to prepare their response.

Mihšihkinaahkwa was the last speaker on the 21st and his comments focused on two points. First, that the lands ceded at the disputed treaty belonged, at least in part, to the Myaamia and any cession of those lands required their approval. Second, he tried to head off any attempt General Wayne might make to use the Treaty of Paris to claim the same land. Like a skilled debater, Mihšihkinaahkwa realized that if the Treaty of Fort Harmar was deemed illegitimate by the council, then his opponent might seek another path to justify Mihši-maalhsa control over the same land. To the Myaamia, the French did not own land in the Ohio and Wabash River Valleys and so could not have ceded it to the British at the end of the Seven Years’ War (1763). Therefore the British could not cede it to the Americans at the end of the American War for Independence, which the Treaty of Paris (1783) brought to a close. The Myaamia, represented by Mihšihkinaahkwa, wanted Greenville to be a new and separate foundation for peace between their communities and the Mihši-maalhsa. They wanted the Treaty of Greenville to establish peace and borders as an independent agreement. The Myaamia could no longer resist the Mihši-maalhsa through violence but they continued to strongly reject the illegitimate treaties of the 1780s.

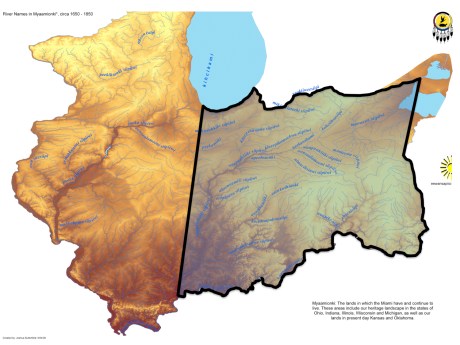

On July 22nd, Mihšihkinaahkwa was the first speaker to rise and address the council. He addressed General Wayne stating that “I wish to inform you where your younger brothers, the Miamis, live, and, also, the Pottawatomies of St. Joseph’s, together with the Wabash Indians.” He disputed the boundary established by the Treaty of Ft. Harmar, as it “cut off from the Indians a large portion of country, which has been enjoyed by my forefathers since time immemorial, without molestation or dispute. The print of my ancestors’ houses are everywhere to be seen in this portion,” the outline of which ran from “Detroit… to the headwaters of Scioto… down the Ohio, to the mouth of the Wabash, and from thence to Chicago” (see map below). He added that now he was prepared to listen to proposals on the issue of a boundary between the Mihši-maalhsa and the gathered groups. Mihšihkinaahkwa concluded, “I came with an expectation of hearing you say good things, but I have not yet heard what I expected.”[22]

Next to rise was the Wyandot leader Tarhe, who reiterated his community’s desires for peace with the Mihši-maalhsa in a strong and poetic speech. He concluded by restating his belief that the Treaty of Fort Harmar was a good foundation for peace and explained to everyone the boundaries originally agreed to in that treaty by the Delaware, Six Nations, Ottawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Wyandot. He argued, in opposition to Mihšihkinaahkwa, that the Treaty of Fort Harmar was the foundation for the “general, permanent, and lasting peace” they were creating at Greenville.[23]

General Wayne followed Tarhe and closed out this fifth day of the council by agreeing that everyone had convinced him of their peaceful intent and that he would review “these belts, speeches, and boundaries, now laid before me, with great attention,” and that they would meet the next day to continue their work.[24]

Over these two days of discussion, Mihšihkinaahkwa staked out two vitally important positions for his people. First, he firmly refuted any treaties that preceded 1795 as illegitimate and therefore not binding on Myaamia communities. He wanted to force General Wayne to negotiate this treaty as the sole beginning point for the relationship between the Fifteen Fires of the United States and his community. If he was successful, then all of the parties at Greenville could close the door to the discord and arguments produced by the treaties negotiated at Forts Stanwix, Harmar, and McIntosh. The Treaty of Greenville could then provide a firm foundation upon which to create peace between all the groups.

Second, he clearly delineated the lands that belonged to his people. It is important to note here, that Myaamia people did have a concept of control over land. Land was held in common by the communities that lived on it and used it, for agriculture, hunting, and gathering. This Myaamia concept of land use also acknowledged that different communities could have overlapping claims to utilize the land, and this is why Mihšihkinaahkwa stated that the land he outlined belonged to the Potawatomi of the St. Joseph’s River, the other Wabash tribes, and to the Myaamia. What is striking about Mihšihkinaahkwa’s definition of a Myaamia land base is that no other leader at the Treaty of Greenville made an attempt to define their lands in a similar manner.

This definition of a land base using clear boundary lines shows a recognition of how Europeans defined land. Previous Myaamia attempts to define their land base usually focused on the center of things, like the Wabash River, rather than marking boundaries, like European nation states of the eighteenth century. It is likely that this external boundary line is indicative of Mihšihkinaahkwa’s collaboration with his son-in-law Eepiihkaanita (William Wells). The historian Harvey Lewis Carter asserted that from 1795 until their deaths in 1812, Mihšihkinaahkwa and Eepiihkaanita should be thought of as joined together in their efforts. Together with Eepiihkaanita, Mihšihkinaahkwa was able to identify Myaamia lands in a way Europeans could clearly understand. Ideally, the Mihši-maalhsa would respect boundaries so clearly identified.[25]

Over the eleven days of the council that followed, the war of words over boundaries and previous treaties continued, but by the end, an agreement for a new peace did finally emerge. In our next article, we will look at the conclusion of the Treaty of Greenville and discuss its impact on the relationship between the Mihši-maalhsa and our ancestors. We will also look at how the treaty affected the transformation of relatively independent Myaamia village communities into a somewhat unified political entity: the Miami Nation.

If you would like to comment on this story, ask general historical questions, or request a future post on a different topic, then please comment below or email me at ironstgm@miamioh.edu. This blog is a place for our community to gather together to read, learn, and discuss our history, ecology, genealogy, and language. I hope we can use this blog as one place to further our knowledge and strengthen our connections to each other and to our shared past.

Click here to continue the story and read the Treaty of Greenville Part 2 by Cameron Shriver

Notes

[1] This battle is often called the “Fallen Timbers” in English, however no Myaamia phrase has ever been recorded for the battle. This article continues to use well-documented place names to refer to the locations where events took place.

[2] Anthony Wayne, Anthony Wayne, A Name in Arms: Soldier, Diplomat, Defender of Expansion Westward of a Nation; the Wayne-Knox-Pickering-McHenry Correspondence, transcribed and edited by Richard C. Knopf (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1960), 354-55.

[3] Anthony Wayne, et al, Agreement to Meet in Greenville to Discuss Peace, January 21-22, 1795, Chicago Historical Society: Anthony Wayne Papers, accessed through War Department Papers at http://wardepartmentpapers.org/docimage.php?id=13027&docColID=14252&page=27

[4] Harvey Lewis Carter, The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 146.

[5] Carter, Little Turtle, 145. Charles Elihu Slocum, History of the Maumee River Basin: From the Earliest Account to its Organization into Counties (Defiance, Ohio, The Hubbard Company, 1982), 223.

[6] Andrew R.L. Cayton, “’Noble Actors’ upon ‘the Theatre of Honour’: Power and Civility in the Treaty of Greenville,” in Andrew R. L. Cayton and Fredrika J. Teute, Contact Points: American Frontiers from the Mohawk Valley to the Mississippi, 1750-1830. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 1998), 239.

[7] American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, Vol. 4, Indian Affairs (ASPIA), no. 1 (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832), 564. Seventeen Myaamia men arrived on June 23. By the end of the counsel on August 7 there were 73 total Myaamia from the headwaters of the Maumee down to the Eel River, 12 Wea and Piankashaw, and 10 Kickapoo and Kaskaskia. Kappler’s Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior), 45.

[8] Cayton, “Noble Actors,” 259-62.

[9] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 567.

[10] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 567. Kappler, Treaties, Vol. II, 45.

[11] Carter, Little Turtle, 147, 153.

[12] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 567.

[13]ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 567. Anthony Wayne, et al, Agreement to Meet in Greenville to Discuss Peace, January 21-22, 1795, Chicago Historical Society: Anthony Wayne Papers, accessed through War Department Papers at

[14] Wiley Sword, President Washington’s Indian War: the Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 28-30. Reginald Horsman, Matthew Elliott, British Indian Agent (Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 1964), 39.

[15] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 567.

[16] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 568.

[17] Harvey Lewis Carter’s biography of Mihšihkinaahkwa remains the most thorough and detailed to date, yet the author does not discuss analyze Mihšihkinaahkwa’s transition to a civil leader, which had its genesis at the first Treaty of Greenville.

[18] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 568.

[19] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 568.

[20] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 569.

[21] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 570.

[22] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 570-71.

[23] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 571.

[24] ASPIA, I, Treaty Minutes, 571.

[25] Carter, Little Turtle, xiii.

Dear George,

This is fantastic work! Thank you so much for posting this. I will use it in my classes.

Sara Clark

Assistant Professor of English as a Second Language

Cuyahoga Community College

Parma, OH 44130

(216) 987-5590

Sara.clark@tri-c.edu

neewe Sara, I hope to have Part II finished before winter.

Aya, I’m so sorry for your loss. dani

Sent from my iPhone

>