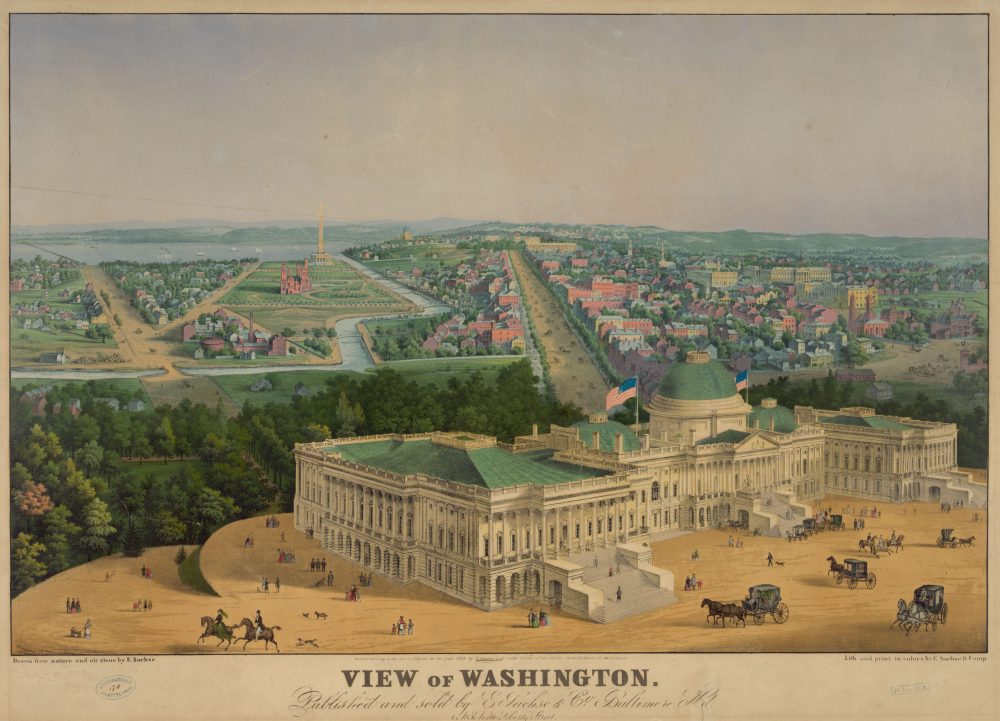

This is the second of a multipart series of blog posts focused on closely examining the transcript of the 1854 Treaty of Washington. The first post in this series provided background to the treaty, took a close look at meetings that preceded the actual treaty negotiation, and described the Miami Nation delegation’s arrival in Meetaathsoopionki ‘Washington, D.C.’

This post examines the first four days of the negotiation and lays out the objectives of the Miami Nation representatives and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. It also looks at the key ways in which non-Myaamia outsiders sought to disrupt the treaty negotiations for their own financial benefit by pitting the Miami Nation against Myaamia people who had legally remained in Indiana following the 1846 removal.

Treaty Negotiations – Day 1 – May 23, 1854

The transcript of the 1854 treaty negotiations is very sparse and poorly written. Past treaty transcripts were often full of detail and attempted to capture the fullness and artistry of the speeches made during complex negotiations. The 1854 transcript is hollow by comparison, but it is still an invaluable historical source. Manypenny’s secretary mostly recorded only the main ideas being communicated and rarely quoted directly from the proceedings. However, the secretary did record a few vitally important quotations that help us understand the bargaining that eventually produced the finished treaty.

It is also important to note that most of the Myaamiaki attending this negotiation did not speak English, and Manypenny and his staff did not speak Myaamiaataweenki ‘the Myaamia language.’ Nearly everyone was reliant on translators in order to communicate. Lenipinšia “Baptiste Peoria” served as translator for the Office of Indian Affairs. Lenipinšia was an elected leader of the Confederated Peoria Nation and spoke Peewaaliaataweenki ‘the Peoria language,’ which is the same language as Myaamiaataweenki with small dialectical differences. Lenipinšia was regularly involved in controversial decisions regarding the administration of the Miami Nation reserve in what would become Kansas. He was also an elected leader of the Peewaalia ‘Peoria’ nation with his own economic interests. The Miami Nation council often felt that Lenipinšia’s economic and political interests influenced his treatment of Myaamia political matters. In 1860, six years after this treaty, the Miami Nation council would officially request that Lenipinšia be removed as translator and replaced with Waapimaankwa ‘Thomas Richardville,’ a Myaamia man born in Indiana who moved to the Miami Nation reservation as an adult.[1]

James Miller served as translator for those representing the Myaamia families living in Indiana. Miller learned the Myaamia language while working as a store clerk selling goods to Myaamia families. He was a part of a network of men who ran stores near where Myaamia families lived in Indiana. The men in this network enriched themselves through selling heavily marked up goods on credit to Myaamia families. These men would regularly claim a large part of Myaamia annuity payments in order to cover these manipulated debts. Miller and Lenipinšia’s attendance at the treaty, and their key roles as translators, demonstrates one part of the influence that outside interests attempted to wield over the treaty process.[2]

The treaty transcript is mostly silent on the issues of daily attendance for specific members of the Miami Nation delegation, but it is assumed that all the nation’s representatives were present each day of the negotiation. Also present through the majority of the negotiation were the representatives of the families of Myaamiaki living in Indiana and a team of U.S. government representatives headed by Commissioner Manypenny.

The first day of the negotiations began with a public reading of the letter that the Miami Nation delegation presented to the commissioner the previous evening. Commissioner Manypenny then asked if the Tribe was willing to sell a portion of their reservation land as they discussed during his visit the previous fall. Neewilenkwanka, the elected akima ‘chief’ of the Miami Nation, acknowledged the request for land, but responded that they also had many old financial claims to make against the U.S. government. On this point the transcript is spotty and incomplete, but it appears that the Miami Nation delegates through Akima Neewilenkwanka were making it clear that there would be no land treaty without Manypenny acknowledging and addressing these outstanding issues. Before breaking for a mid-day meal, Manypenny agreed to address both the Miami Nation’s claims and the sale of land in the treaty.

After they returned from their meal, Manypenny admitted a major mistake on the part of the U.S. government: the reservation of the Miami Nation was “much less than 500,000 acres,” which was the amount promised to the nation in the Treaty of 1846. Over time it would be ascertained that the nation’s reservation was around 325,000 acres in size and that they had been cheated out of around 175,000 acres of land.[3] Following this admission, the negotiations took a break for the day.

Treaty Negotiations – Day 2 – May 25

On the second day of negotiation, the treaty reconvened with Manypenny throwing a political bomb into the discussion. He reported to the Miami Nation delegates that a “gentleman… from Indiana” came to see him to argue that the “West[ern] Miamies were in favor of dividing the land with [the] Indiana Miamis.” This man added that the letter the Miami Nation delegates presented did not represent their true views. Manypenny followed up by asking Neewileenkwanka, did “that paper contain your true views?” As we shall see later in the negotiations, it is likely that this “gentleman” was Andrew Jackson Harlan, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives who lived in Marion, Indiana near to the Mihšiinkweemiša Reserve.

The record does not make this clear, but it appears that Representative Harlan had assumed responsibility for speaking on behalf of the representatives of Myaamiaki living in Indiana. There is no evidence offered in support of his allegations in the treaty transcript or associated materials. Manypenny had prior knowledge of the Miami Nation’s leadership and the letter they presented him with certifying their power to negotiate on behalf of the nation. The commissioner had no reason to allow Harlan’s accusations onto the floor of the negotiation, and yet he asked the Miami Nation to officially respond. It remains an open question as to why he allowed this argument to proceed.

In response to the accusation, Neewilinkwanka stated that he “[d]id not come here for business of Indiana folks.” He had come to address the concerns presented in the letter. The Miami Nation leader acknowledged that four years ago some Myaamia individuals living in Indiana had asked about receiving land within the Miami Nation’s reserve. However, he clarified, this had no impact on the current negotiations; he would “never agree to let any of those Indians come into the treaty.” Akima Neewilenkwanka added what must have been a venomous conclusion to his response “You see how our blood come around to swindle us right off.”

Apparently, Manypenny did not wholly accept Neewilenkwanka’s response and proceeded to read aloud the text Harlan had shared the previous night. Likely feeling as though he had sufficiently addressed the accusations, Neewilenkwanka deftly turned the discussion away from this external interference to the issue of the mispayment of annuities to those not recognized as Myaamia. He demanded to know why these payments were being made without the Miami Nation’s approval. The Commissioner continued the trend of participants talking past each other and proceeded to ignore Neewilenkwanka’s demand and instead asked about the Miami Nation’s interest in selling land. The delegation replied that “[t]hey have not decided yet.” Neewilenkwanka closed the day’s negotiations by reminding Manypenny that they had set clear conditions during the Commissioner’s visit in the preceding fall: “settle the claims and then he will talk about the land.”[4]

Treaty Negotiations – Day 3 – May 26, 1854

The next day, the negotiation opened with the Commissioner stating that he had been told that the “Miamies of Indiana desire to talk with him this morning.” He acknowledged “heretofore that they were silent.” Mihšiinkweemiša rose and declared that “they did not come here to cause difficulties.”[5] Once again, the treaty record is not clear, but it appears that Mihšiinkweemiša was uncomfortable with Harlan’s interference in the negotiations. Mihšiinkweemiša was the head of the family descending from Mihtohseenia, which had been exempted from removal through the terms of the Treaty of 1840. His family, as well as others living in Indiana, still had treaty rights tied to their lands and received annuity payments tied to pre-removal treaties.[6] On the third day of the negotiation, Mihšiinkweemiša was interested in how the $25,000 annuity would be divided and what would happen to his family’s portion of a future lump sum payment.

Commissioner Manypenny responded to Mihšiinkweemiša that the Myaamiaki living in Indiana “have no power” but that the political power to negotiate treaties “is in the tribe west, whatever that tribe does here will be binding upon the Indiana Miamies.” The Myaamiaki living in Indiana could decide how their part of the lump sum payment from the $25,000 annuity was managed and paid out, but the decision to convert the annuity into a lump sum wholly belonged to the Miami Nation. Manypenny concluded by asking Mihšiinkweemiša if he and the other four representatives from Indiana families have “any paper or authority to act from their people in Indiana[?]” Mihšiinkweemiša replied that he and the other family representatives “have no power” and that “his people don’t know anything about this treaty.” At this point the commissioner appeared to grow frustrated with Mihšiinkweemiša and rudely asked him “[w]hat did they come here for?” Mihšiinkweemiša replied that he had come to address the issue of those previously mentioned groups who were wrongly receiving Myaamia annuity payments. He wanted “to meet their western brethren to show them what persons were drawing money in Indiana.” He added that he “came here for no other purpose… not to have anything to do with a treaty.”[7]

What emerges from this discussion is that Myaamia people and the U.S. government agreed that the Miami Nation was located west of the Mississippi on their collective reserve in Waapankiaakamionki. Myaamia people living in Indiana were recognized as a part of the nation but living outside of its boundaries. They could receive land within the reserve, vote in elections, and even be elected to government if they moved west. Yet, if they stayed in Indiana, they ceded this political authority to those who lived within the nation. Prior to the Treaty of 1854, all Myaamiaki were treated roughly the same when it came to annuity payments. This treaty changed that financial parity and created two separate payment classes for Myaamiaki: one for those living within the nation and one for those living in Indiana. However, this separation of payment classes did not create a governmental unit in Indiana. Following this treaty, there was still only one organized government representing Myaamia and carrying forward the treaty obligations of the nation and this government was located in Waapankiaakamionki west of the Mississippi.

After the discussion of the status of Myaamia living in Indiana, Manypenny then moved on to conclude the day’s negotiations by restating the options for how to deal with the lump sum payment stemming from the $25,000 annuity. He added that although the treaty could be decided with only the Miami Nation’s approval, he hoped “to have the concurrence of the Indiana Miamies.” Mihšiinkweemiša then agreed that if the permanent annuity was ended that the U.S. government would invest the portion of the lump sum owed to Myaamia families living in Indiana and pay them yearly from the interest generated by the investment. Manypenny finished the day by reading aloud the text of a rough draft of the treaty. Before the meeting closed, Neewilenkwanka protested that he did not understand the status of Myaamia people from the Eel River community because a “good many have been drawing money in the West, with them,” and that the Miami Nation wanted money to start and maintain a school on their reserve. As the day’s conversation closed, Neewilenkwanka remained silent on the Miami Nation’s perspective on ending the permanent annuity.[8]

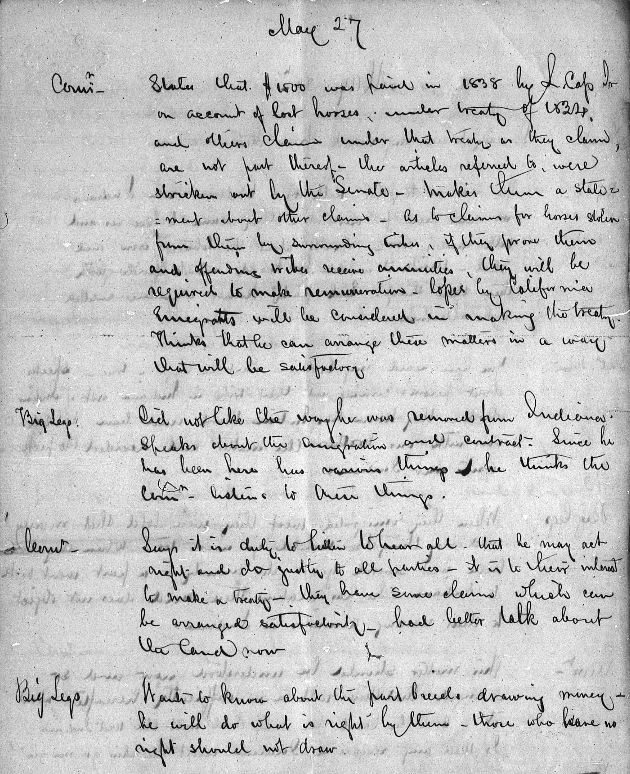

Treaty Negotiations – Day 4 – May 27, 1854

According to the record, this fourth day of negotiation was fairly brief. Commissioner Manypenny opened the day by reporting on how his agency planned to address the Miami Nation’s claims regarding loss of livestock. Neewilenkwanka’s opening statement reiterated that he “[d]id not like the way he was removed from Indiana,” and asked Manypenny to examine how the removal was conducted and look into the contracts used to pay for the removal. In response, Manypenny agreed to listen to all complaints, but asked them to consider the treaty as the means by which they could address all their grievances. Demonstrating his stubborn determination on behalf of his community, Neewilenkwanka again reiterated the Miami Nation’s desire to address claims and issues of wrongfully paid annuities before discussing the cession of land. Likely sensing that the conversation had reached an impasse, the commissioner deferred on the issue of claims. As he prepared to adjourn the meeting, Manypenny asked the Miami Nation leadership to discuss the issue of land cession and reiterated that all claims will be addressed in the treaty. If they were not happy with how those claims are addressed, the commissioner added, “they need not sign it.”[9]

During the first four days of negotiation, tensions rose for a variety of factors. Representatives of the Miami Nation clearly harbored feelings of hurt and anger that stretched all the way back to the trauma of the 1846 forced removal. They were also suspicious of the way in which some individuals and families were receiving annuities in Indiana. They clearly knew and recognized many of the Myaamiaki living in Indiana as their kin, but were suspicious of payments happening at such a distance from their government’s watchful eyes. As we will come to see, they had good reason to be suspicious. These first days were critical in framing the position of the Myaamiaki living in Indiana. They were clearly not representing the Miami Nation and attended the treaty as individual guests whose interests were narrowly focused on their families. Manypenny sought their approval, but he explicitly stated that it was not required for the treaty to proceed.

In Part 3 of this series on the 1854 Treaty of Washington we will see how the Miami Nation and Myaamiaki living in Indiana worked together to create a sense of unity and then struggled to maintain that unity in the face of outside interference and the commissioner’s constant pressure for land sessions.

Notes

[1] Meghan Dorey and George Ironstrack, keehkaapiišamenki: A History of the Allotment of Miami Lands in Indian Territory (Miami, OK: Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, 2015), 8-9. Minutes of the Miami National Council from November 12, 1860, Miami Nation Council Book 1, Myaamia Heritage Museum & Archive, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami, OK.

[2] United States. 1904. Kappler’s Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. II (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior), 641. Full text of the treaty is available through Oklahoma State University at https://cdm17279.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/kapplers/id/29625/rec/1 and through the University of Wisconsin at https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AAKQKRUJZNAQM39A. Stewart Rafert, The Miami Indians of Indiana: A Persistent People, 1654-1994 (Indianapolis, Ind.: Indiana Historical Society, 1996), 99, 123-24.

[3] Treaty of 1854, “Miami Conference May 23, 1854.” Ratified treaty no. 274. Documents relating to the negotiation of the treaty of June 5, 1854, with the Miami Indians (available digitally at https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AAKQKRUJZNAQM39A). Bert Anson, The Miami Indians, 1st ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 239, 241 (n. 9).

[4] Treaty of 1854, “May 25.”

[5] Treaty of 1854, “May.” The secretary forgot to enter the full date on the next entry in the record. Because this entry occurs between May 25 and May 27, it is safe to assume this meeting was in fact on May 26, 1854.

[6] Diane Hunter, “Exemptions from Removal.” Aacimotaatiiyankwi: A Myaamia Community Blog. Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. July 2, 2021. https://aacimotaatiiyankwi.org/2021/07/02/exemptions-from-removal/. Rafert, The Miami Indians of Indiana, 99-100.

[7] Treaty 1854, “May 26.”

[8] ibid. The Eel River Myaamiaki were a subgroup of the Miami Nation with their town originally based on the Kineepikomeekwa Siipiiwi ‘Eel River’ in what is today Indiana. Over time this community was absorbed either into the Miami Nation in what became Kansas or into Myaamia families living in the area around Peru, Indiana.

[9] Treaty of 1854, “May 27.”

Leave a comment