This is the third of a multipart series of blog posts focused on closely examining the transcript of the 1854 Treaty of Washington. In the first two parts (Part 1 & Part 2) of this series, we summarized a bit of the background of the 1854 Treaty of Washington and closely examined the first four days of negotiation. We saw the agendas of attendees rapidly emerge and sharpen. Akima Neewilenkwanka, representing the Miami Nation, wanted to address financial claims tied to issues that stretched back to the mishandling of the 1846 removal. These claims included, but were not limited to, the loss of property during the removal, the failure of the U.S. to pay certain funds at all, and the mispayment of annuities to individuals and families that the nation believed were not Myaamia. Neewilenkwanka was clear during those first four days: the leadership of the Miami Nation would only discuss ceding more land after these claims were addressed. Mihšiinkweemiša, the head of one of the Myaamia families living in Indiana, made it clear in the early days of negotiation that he was not there to negotiate a treaty. He recognized that he had no power to do so, but was attending to look after the needs of his family. His primary concern was the continuation of the $25,000 annuity, which was created at the Treaty of the Wabash in 1826 and was paid to all Myaamia families. In these first days, Commissioner Manypenny pushed his two main priorities: ending the $25,000 and convincing the Miami Nation to relinquish more of its land to the United States.

Day 5 – May 30, 1854

The fifth day of treaty negotiations opened with a statement of unity from Akima Neewilenkwanka, “You see us together with our brothers from Indiana. We came here for ourselves—they came to see us and talk matters over.” He concluded his opening speech by agreeing that it would be hard not to share resources like tobacco, salt, iron, and steel with their Myaamia relatives living in Indiana, and that “[e]ach party knows who are entitled to be Miamies.” The Miami Nation and the families living in Indiana would work together to deal with the issue of who would receive Myaamia annuity payments. An unidentified Myaamia from Indiana rose to acknowledge that they agreed with the Miami Nation’s position. Neewilenkwanka then spoke again to confirm that “he has relatives there and does not object to their receiving annuities in Indiana.”[1]

The opening statements on the fifth day indicate that the official representatives of the Miami Nation and the Myaamiaki from Indiana met together at some point before the day’s meetings began. Based on the evidence in the treaty transcript, it appears that this conversation occurred without the presence of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Myaamia people had decades of experience resisting United States attempts to use divide and conquer strategies at the negotiating table. At the start of the fifth day, it seemed like the leadership of the Miami Nation and their Indiana relatives were trying to close up any gaps between them that Manypenny might try to exploit.

The commissioner replied to the unified joint opening statements that this matter was considered settled and that he expected there to be no difficulty thereafter. Manypenny then asked if in addition to Mihšiinkweemiša’s family reserve if there were any other reserves in Indiana. Speaking to the Myaamia from Indiana he then suggested that they sell their reserved land or whatever portions they did not use. The commissioner then changed the subject to the permanent annuity and stated his intention to transform the perpetual annuity into a lump sum which would be distributed over a number of years in large payments. Regarding the annuity, Neewilenkwanka stated that his nation did not “want it that way” but that they “wish the annuities to run on” and “don’t want to change [the] old treaty.” Akima Neewilenkwanka concluded that “he has been told that it is $25000 for ever.”[2]

Manypenny tried to drive the issue of the annuity forward by warning that “[t]he annuity dies with the extinction of the tribe” and that he was promising a lump sum of at least $375,000 payable over five years. The commissioner’s embedded threat was that if the Miami Nation government ceased to exist, then individual Myaamia people would lose the entire $25,000 annuity. This was no idle threat given the collapse of the Myaamia population within the nation’s reserve following removal. Neewilenkwanka had already firmly stated his nation’s position on the annuity, and he remained silent in the face of Manypenny’s warning.

The conversation on this 5th day then moved towards a close with a discussion of the cession of land and the division of the remaining reserved lands. The Myaamia akima opened this part of the discussion by stating that they “[t]hought we had a large country” and he presented the commissioner with a paper that demonstrated this. The treaty transcript does not spell this out; however, it is highly likely that the Miami Nation was presenting their claim that their reservation was supposed to contain 500,000 acres, but that the U.S. government had provided them only with around 325,000 acres.[3] Neewilenkwanka added that they would like to reserve 200 acres for each person and maintain a tract to be held in common by the nation. The meeting then adjourned as the Miami Nation representatives agreed to consult with each other over the question of the sale of the remaining portion of their reserve.

Day 6 – May 31, 1854

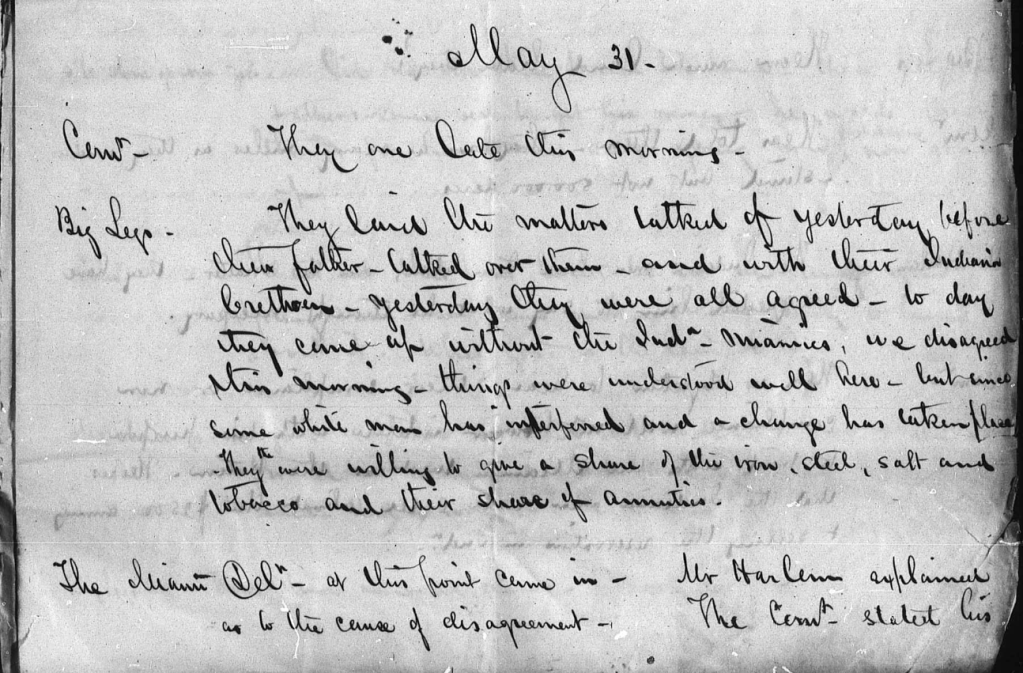

On the final day of May the treaty negotiation opened with another surprising change of direction. Unlike previous days, the Miami Nation representatives arrived late and came in without the Myaamiaki from Indiana. Akima Neewilenkwanka acknowledged that “[t]hey laid the matters talked of yesterday before their father” and ”talked over them and with their Indiana brethren.”[4] He continued, “yesterday they were all agreed” but that “to day [sic] they came up without the [Indiana] Miamies… we disagreed this morning” because “some white man has interfered and a change has taken place.” Neewilenkwanka repeated his commitment to share a part of the tobacco, salt, iron, and steel as well as a share of the annuities with their relatives living in Indiana.[5]

The Miami Nation akima’s speech was then cut off as the Myaamiaki from Indiana entered the room along with Indiana Representative Andrew Jackson Harlan. Harlan explained that the Myaamia from Indiana would not agree to transform the $25,000 annuity into a lump sum. The treaty transcript does not speak to the tone of the meeting, but it seems likely that both Akima Neewilenkwanka and Commissioner Manypenny were irritated by Harlan’s interjection. He had no official role in the negotiations and had clearly disrupted the harmony that had developed just the day before. Manypenny responded to Harlan by saying he only needed the agreement of the Miami Nation in order to terminate the $25,000 annuity via the treaty. Following this statement the Myaamiaki from Indiana stood and left the negotiation. This must have been a shocking turn of events to everyone involved.[6]

In a seeming attempt to inject some clarity into the discussion, Neewilenkwanka called on a non-tribal U.S. citizen named David Lykins to explain the Miami Nation’s position. Lykins was a well-known school teacher and missionary who worked with Myaamia-Peewaalia ‘Miami-Peoria’ speakers near the Miami Nation reservation. The Miami Nation’s use of Lykins on the sixth day of the negotiation potentially speaks to their distrust of the translations provided by Lenipinšia ‘Baptiste Peoria.’ Lenipinšia was an akima ‘chief’ among the Peoria and as an official Indian Agency interpreter was involved in many disputed decisions in the Miami Nation’s reserve. He was an advocate for merging the Miami Nation with the Peoria Nation, a position that the Myaamia community disliked.[7] Lykins, speaking for Neewilenkwanka, declared that “they want to make a treaty as the Miami nation.” The commissioner replied that he would respect the treaty rights of the Myaamiaki living in Indiana but not so far as letting their opinions interfere with the rights of the Miami Nation, but he hoped that the differences between the two groups could be resolved. Neewilenkwanka seems to have accepted the commissioner’s position and from this point they move on to discussing the details of the treaty.[8]

Manypenny opened by offering a lump sum payment of $400,000 in exchange for the end of the $25,000 annuity. They then discussed how much land the Miami Nation Reserve contained. Manypenny admitted that the reserve does not contain 500,000 acres as had been promised in the Treaty of 1840. At this point, the negotiation was once again interrupted by Harlan as he reported “the Indiana men have been talking over the matter” and “they have requested him to say what he thought necessary.” The commissioner, who must have sounded slightly repetitive, reiterated that he was willing to listen but ‘their compliance or non compliance will not however interfere with his purpose to treat with the Miamis West as the nation.” Manypenny declared his hope “that the Indiana men will agree about the $25,000 annuity & selling the reservations in [Indiana].”[9]

At this point, Manypenny spoke directly to Mihšiinkweemiša and pleaded “open your ear[s].. [t]hese the [Western] Miamis have agreed that you shall have your share of the $25000 [annuity] the salt, tobacco, iron & steel—and they have the blacksmith, miller & school fund.” He argued that they could use the money from the lump sum payments to improve the land on their family reserve. The commissioner asserted that he would not cheat Mihšiinkweemiša out of his land, but that he would like to buy the part of the reserve that was not useful to them. It is not clear in the record, but Mihšiinkweemiša’s reply feels like it is full of anger. He responded that he “[d]id not come here to sell his land.” However, he added, “these half breed[s] & others came here to get his money,” and he wanted “these things for his women and young men & children, now growing up.” Mihšiinkweemiša was looking after his kin’s future. To care for his family he knew they needed to hold on to their land and protect their annuity payments from those who were not a part of the community. Yet Manypenny would not give up, and he pushed once again for Mihšiinkweemiša to consider selling. In response, Mihšiinkweemiša replied by firmly closing the door to a possible sale by harkening back to the Treaty of 1838 and the promise of Akima Pinšiwa “Chief Jean Baptiste Richardville” that his land would never be divided.[10]

Following Mihšiinkweemiša’s stern refusal, Akima Neewilenkwanka and Commissioner Manypenny resumed their conversation about old claims and new land cessions. They agreed that the claims would be addressed in the treaty but disagreed over the price per acre that the U.S. would pay for the parts of the reserve that the Miami Nation would agree to sell.

At the end of the day’s negotiation, Manypenny asked the Miami Nation “to decide definitively about the $25000 [annuity].” The Myaamia akima confirmed that they agreed to “to let the Indiana Miamies have their share-to be paid in six years and that the salt [and etc.] may be converted into money.” Neewilenkwanka added, “they never got school moneys” and “want them now.” He pushed for the inclusion of treaty provisions that would ensure the payment of school funds due from the past and that they would continue to be paid going forward. Manypenny agreed that he would try to address the issue of old school payments and then closed out the day by calling the nation’s attention to legislation passed by Congress that required withdrawal of Miami Nation funds to pay descendants of the Eel River Village for the eight years they did not receive their payments. No reply to this information was noted by the secretary.[11]

In this third part of our series on the 1854 Treaty of Washington, we saw that the Myaamiaki in Meetaathsoopionki came together to create a sense of unity that recognized the political primacy of the Miami Nation as well as the kinship connections between the nation in the west and Myaamia families living in Indiana. Yet, between the end of the 5th day and the start of the 6th something dramatic occurred to rupture this unity. Representative Harlan appears to have interfered around the issue of the $25,000 annuity. It is never stated, but seems probable that Harlan represented business interests back in Marion, Indiana who were accustomed to siphoning off some of this annuity as it was paid to the families living nearby. Commissioner Manypenny further inflamed the situation by pressuring Mihšiinkweemiša to sell a part of his family reserve. In the end of part three, we see how Manypenny allowed the Myaamiaki from Indiana to offer their opinions about the treaty, but that the ultimate decisions remained with the official representatives of the Miami Nation. In the next post of this series, we will see how the final text of the treaty comes together.

Notes

[1] Treaty of 1854, “Miami Conference May 30, 1854.” Ratified treaty no. 274. Documents relating to the negotiation of the treaty of June 5, 1854, with the Miami Indians (available digitally at https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AAKQKRUJZNAQM39A).

[2] Treaty of 1854, “May 30.”

[3] Bert Anson, The Miami Indians, 1st ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 239-40.

[4] “Father” is a metaphoric addressing term that Myaamia people and others used to refer to the French King, the British King, and eventually the President of the United States and his delegates. Originally this was a term used with a specific set of Myaamia cultural expectations: fathers were to show only love to their children and provide them with what they needed to be well-fed and well-sheltered. However, Myaamiaki and other Indigenous peoples had long since given up on these expectations when dealing with Europeans and Euro-Americans. By that point the practice of using this term was ingrained in the political culture of the Miami Nation.

[5] Treaty of 1854, “May 31.”

[6] ibid

[7] Six years after this treaty, the Miami Nation would officially petition to have Lenipinšia removed as their interpreter and have Waapimaankwa “Thomas Richardville” installed in his place. Minutes of the Miami Nation Council from October 29, 1860, Miami Nation Council Book 1, Myaamia Heritage Museum and Archive, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, Miami, Oklahoma; ibid Minutes of the Miami Nation Council from November 12, 1860.

[8] Treaty of 1854, “May 31.”

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] ibid. The Eel River Village community was originally one of the many Myaamia towns that made up the greater Myaamia community at the time of the first Treaty of Greenville in 1795. For reasons that can only be speculated about, Myaamia leadership at that treaty secured a separate annuity for the Eel River town. In the years that followed, the Eel River community negotiated two separate treaties with the United States, which led to a separate annuity structure for this sub-group of Myaamia. Following the 1846 forced removal, the Eel River community became incorporated into either the Miami Nation on their reservation in the west, the family of Mihšiinkweemiša near Marion, Indiana, or the Godfroy family on their treaty reserve near Peru, Indiana. Harvey Lewis Carter, The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 146-47; Anson, The Miami Indians, 228; Stewart Rafert, The Miami Indians of Indiana: A Persistent People, 1654-1994 (Indianapolis, Ind.: Indiana Historical Society, 1996), 133, 165-66; Bert Anson, “Chief Francis Lafontaine and the Miami Emigration from Indiana.” Indiana Magazine of History 60, no. 3 (1964), 267.

Leave a comment