ayaapia apwaaminki eesaahsonta. Eewikaalinta ayaapiali.

miišimaaha, aalinta mihtohseeniaki, niiši-‘hkwa iišišiiniciki.

eesaahsonciki ceeki teehtawaki aweehsaki alookayewaanki.

‘Ayaapia was tattooed on his thigh. A picture of a buck deer had been drawn on him.

Long ago, some people, that’s what they would do.

They were tattooed on their skins with all kinds of animals.’1

Eesaahsinki ‘tattooing’ is a cultural practice that has a deep history within the Myaamia community. This quote from Waapanaakikaapwa ‘Gabriel Godfroy’ highlights one way skin markings were talked about within Myaamia stories. In the context of this story, a Kiikaapwa ‘Kickapoo’ man has an image that prominently features his personal name on his thigh. This image matched marks that he made on trees that depicted his war record. His eesaahsioni ‘tattoo/skin marking’ represented his place within his community and served as an identifier for his enemies, who sought him out on the battlefield.

Language of Skin Marking and the Words We Use

In general, eesaahsinki ‘tattooing/skin marking’ is the process by which small punctures or cuts are made in the skin and ink or pigment is introduced to the dermis layer of our skin. The English word tattoo comes from the Samoan word tatau, which references the tapping style of skin marking common throughout Polynesia.2

Many Indigenous practitioners use the English phrase “ancestral skin marking” or their language’s term for the art form. In Myaamiaataweenki, we use the noun eesaahsioni ‘tattoo’ and various verbs like eesaahsiyankwi ‘we are tattooed’ to refer to this practice.

Eesaahsinki Throughout History

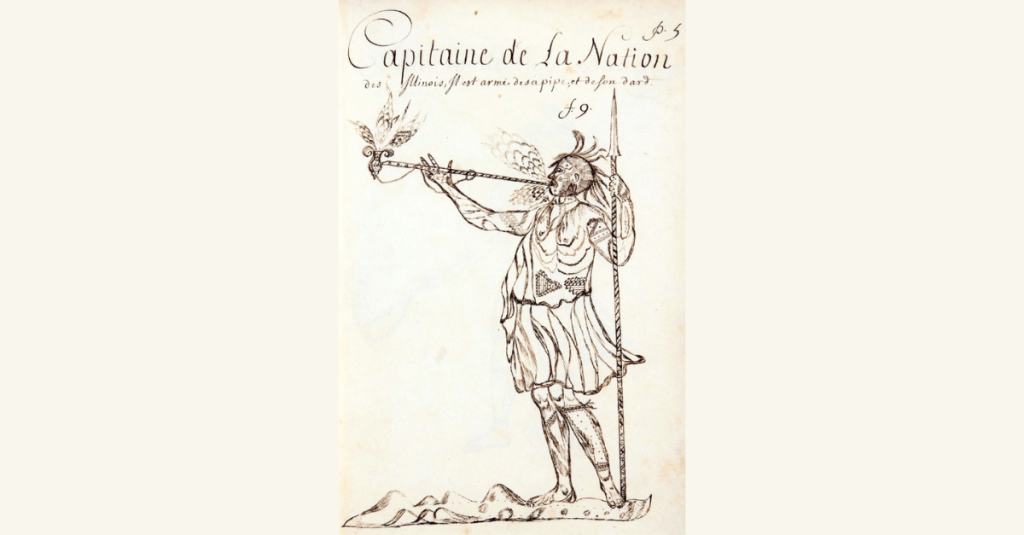

In the earliest years of contact with Europeans, they noted that Myaamia people were heavily marked with eesaahsiona ‘tattoos.’ The markings were not random, but appeared to be tied to age, gender, and status within the Myaamia community.

In the late 1600s or early 1700s, Pierre-Charles de Liette noted:

“They are tattooed behind from the shoulders to the heels, and as soon as they have reached the age of twenty-five, on the front of the stomach, the sides, and the upper arms.”4

De Liette’s note that age was tied to eesaahsinki parallels what C.C. Trowbridge was told in 1824 about body painting: that only those who had achieved a certain age and status in community could paint themselves using vermillion, a red ochre.5

We do not have a lot of specific detail about the meanings behind the numerous eesaahsiona that Myaamia people received. In general, neighboring Indigenous communities used skin markings to represent their home community, their family or clan, their personal name, and their life accomplishments. We can be fairly certain that Myaamia people similarly used eesaahsinki.

A Practice Interrupted

Following the end of the Mihši-maalhsa Wars, Myaamia communities made a difficult series of cultural and political transitions. These transitions accelerated after the end of the War of 1812 as the U.S. dramatically increased the pressure to cede land and remove west of the Mihsi-siipiiwi ‘Mississippi.’ It is during this period that the practice of eesaahsinki ‘tattooing’ went to sleep within Myaamia communities.

Europeans and Americans had strong biases against tattoos as visible signs of savagery and criminality. It is possible that continual negative reactions to eesaahsiona led Myaamia people to move away from the practice. In this period, our leaders regularly stated that one of our key goals was to develop positive interactions with our new American neighbors. It’s easy to see how our ancestors might have modified their body decoration, like eesaahsiona, and clothing to ease social interactions between their community and their neighbors.

The dormancy around eesaahsinki must have been fairly rapid and not widely talked about. By the late 1800s, there was little to no memory of the practice among the Myaamia. One of the most knowledgeable culture bearers of the late nineteenth century, Waapanaakikaapwa ‘Gabriel Godfroy,’ stated:

moohci ninkihkiilimaahsoo, kati eesaahsotiiwaata myaamiaki.

moohci ansihke nineewaahsoo. ninoontansoo, kati eesaahsonci

myaamiaki.

I don’t know whether the Miamis would tattoo each other.

I never saw them. I never heard that Miamis would get tattooed.6

Waapanaakikaapwa was born in 1834 to a prominent leadership family in the Myaamia communities around Kiihkayonki ‘Ft. Wayne, Indiana,’ and Iihkipihsinonki ‘Peru, Indiana.’ His mothers, Seekaahkweeta and Waapankihkwa, were prominent female leaders and storytellers. His father, Palaanswa, was a prominent war leader in his youth and was one of the most influential political leaders in the Myaamia Nation that developed following the end of the Mihši-maalhsa Wars.

All of his parents were born during the period of endemic warfare with the U.S. and came of age in early years of the treaty period. As a result, they apparently did not carry ancestral skin markings and knew very little about the practice of eesaahsinki among Myaamiaki. Waapanaakikaapwa learned the words in Myaamiaataweenki to talk about tattoos, but not much else about the practice in our community.7

Revitalizing Myaamia Tattooing Practices

In the last five years, cultural leaders and teachers in the Eemamwiciki movement have been increasingly asked to create more opportunities to learn more about the practice of eesaahsinki by our ancestors. As a result, a team has started a research project to explore this topic more and prepare materials for sharing what we are finding with our community. Within the next year, community members will be able to participate in a course about eesaahsinki on Šaapohkaayoni, the Myaamia education portal.

Footnotes:

- “Aalhsoohkalinta Kapia ‘Story of Kaapia’, Version 2 in David J. Costa, As Long as the Earth Endures: Annotated Miami-Illinois Texts (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022), 289. ↩︎

- Oxford English Dictionary, “tattoo (n.2),” December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/3437319567. ↩︎

- Robert Michael Morrissey, People of the Ecotone: Environment and Indigenous Power at the Center of Early America (University of Washington Press, 2022), 197-204. ↩︎

- Pierre de Liette, “Memoir concerning the Illinois Country, ca. 1693,” in Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, vol. XXIII: The French Foundations, ed. Theodore Calvin Pease and Raymond C. Werner (Springfield, 1934), 328. ↩︎

- “Formerly none were permitted to paint with vermillion or other paint but black or in any other manner to assume the practices of men until after the age of sixteen and if characterized by weak minds and want of ambition and energy, this period was extended to seventeen or eighteen.” Charles C. Trowbridge and W. Vernon Kinietz, Meearmeear Traditions (Ann Arbor [Mich.]: University of Michigan Press, 1938), 18. ↩︎

- There were three bilingual versions of this story recorded from Waapanaakikaapwa ‘Gabriel Godfroy.’ One by Albert Gatschet and two by Jacob Dunn. In Gatschet’s version Waapanaakikaapwa is recorded as stating that Myaamia people tattooed in the same fashion as the Kickapoo man described in the story, which he later disputed. In the latter two versions, Dunn likely explicitly asked Waapanaakikaapwa to clarify what he knew about Myaamia tattooing practices. We also cannot discount the impact of the trauma and loss produced by the decade or more of warfare on Myaamia community practices and knowledge. Costa, As Long as the Earth Endures, 290. ↩︎

- Circa 1821, a British observer, James Buchanan, who was traveling in the Great Lakes region observed: “Tattooing is now greatly discontinued. The process is quickly done, and does not seem to give much pain. The have poplar-bark in readiness, burnt and reduced to powder; the figures that are to be tattooed are marked or designated on the skin; the operator, with a small stick, rather larger than a common match (to the end of which some sharp needles are fastened) quickly pricks over the whole so that blood is drawn; then a coat of the above powder is laid and left on to dry.” James Buchannon, Sketches of the History, Manners, and Customs of the North American Indians (New York: W. Borradaile, 1824), 96-97. See e-version at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100265223/Home ↩︎

Leave a comment