It was a murder. Or so it appeared.

John Crooks seemed like a nice young man. Puzzled by his sudden demise, his associates said he was fair, decent, unmarried, and sober. It was a mystery how he had ended up this way.

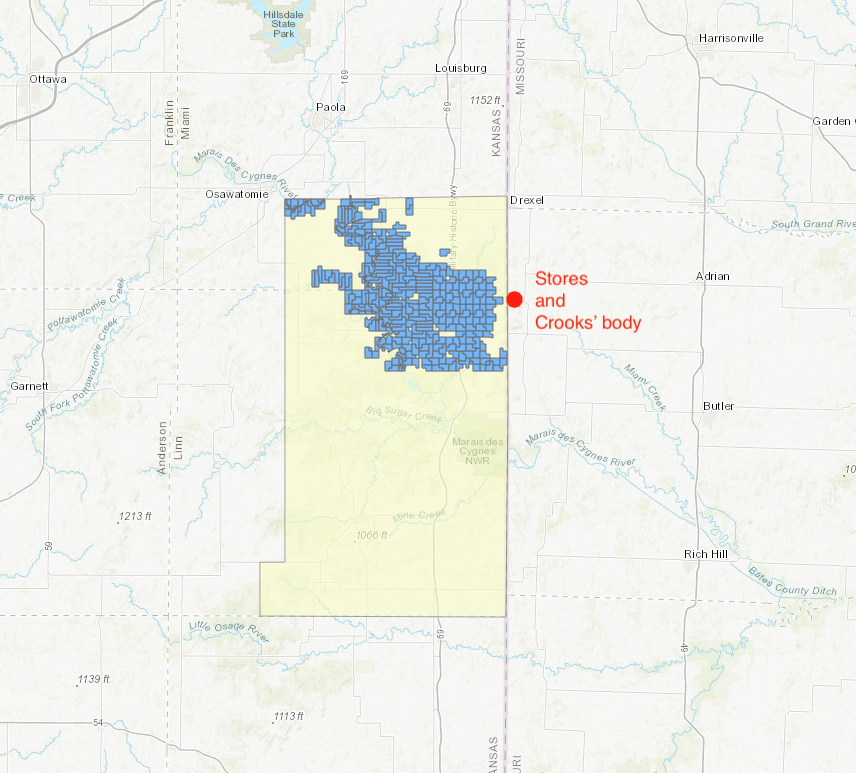

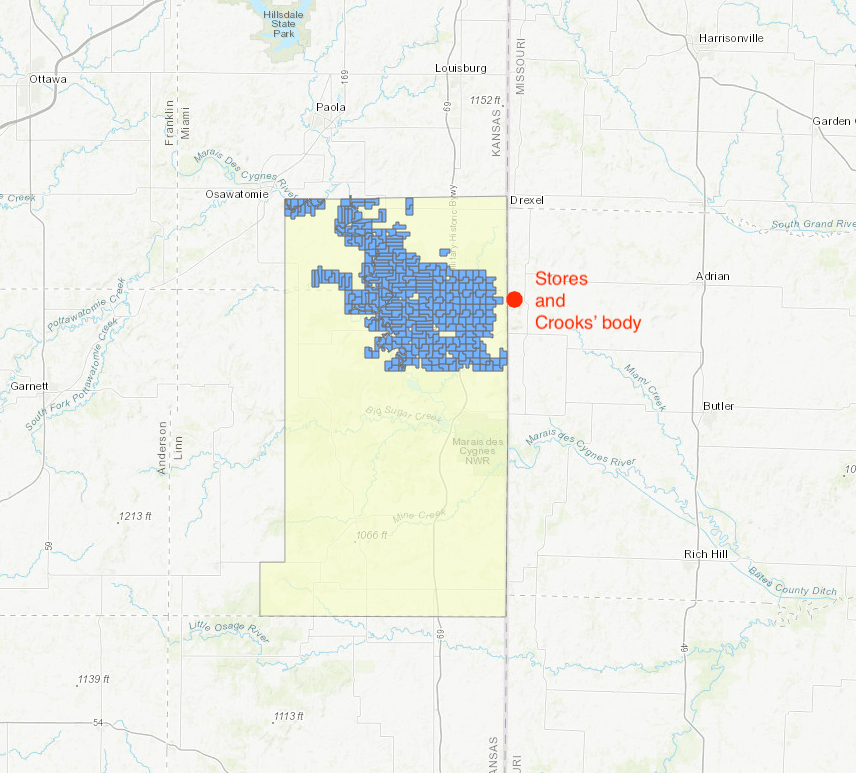

Crooks’ body was found adjacent to the Miami Reservation on the state line between Kansas Territory and Missouri. He lay by the creek’s edge, as if he had just gone to fetch water. One witness said “his pantaloons were lying” twenty steps from the creek, “as if he had just slipped them off.” His face was underwater, but his legs were dry on the bank. It was odd, no doubt about it.

I came across this story while searching for evidence of “Indian rings” in and around the Miami reservations in both Kansas and Oklahoma. These Indian rings were merchants known for colluding to profit from Native American business, either by fraud, embezzlement, or other crooked dealings. Documentation about Crooks’s death was filed along with economic papers retained by the Office of Indian Affairs. It is titled simply “File 57.”

All I know for sure is that Crooks lay dead in the springtime of 1849, and the investigation into those circumstances reveals a slice of life in the immediate post-removal years in Kansas.

The documents in File 57 in the National Archives in Washington, DC, focused on Crooks. That’s where we begin.1

John Crooks had migrated West in the summer of 1848. John S. Crooks2 and John W. Miller3 were familiar with the Miami community, having lived in the heart of Miami County in Peru, Indiana. Both had clerked for Indian traders in the area. Following the Myaamia removal in late 1846, they planned to move to the border of the Miami Reservation (in Kansas Territory), setting up a trading outfit just over the Missouri border. They incorporated as Miller & Co., joining “together in the art trade or business of Merchandizing in the Indian Country in the territory of Missouri.” Miller remained in Peru, and Crooks built a home and store near the Miami village (which local traders frequently called “the Miami Station” and sometimes “Miami Mission”) on the Marais de Cygnes River adjacent to the reservation.

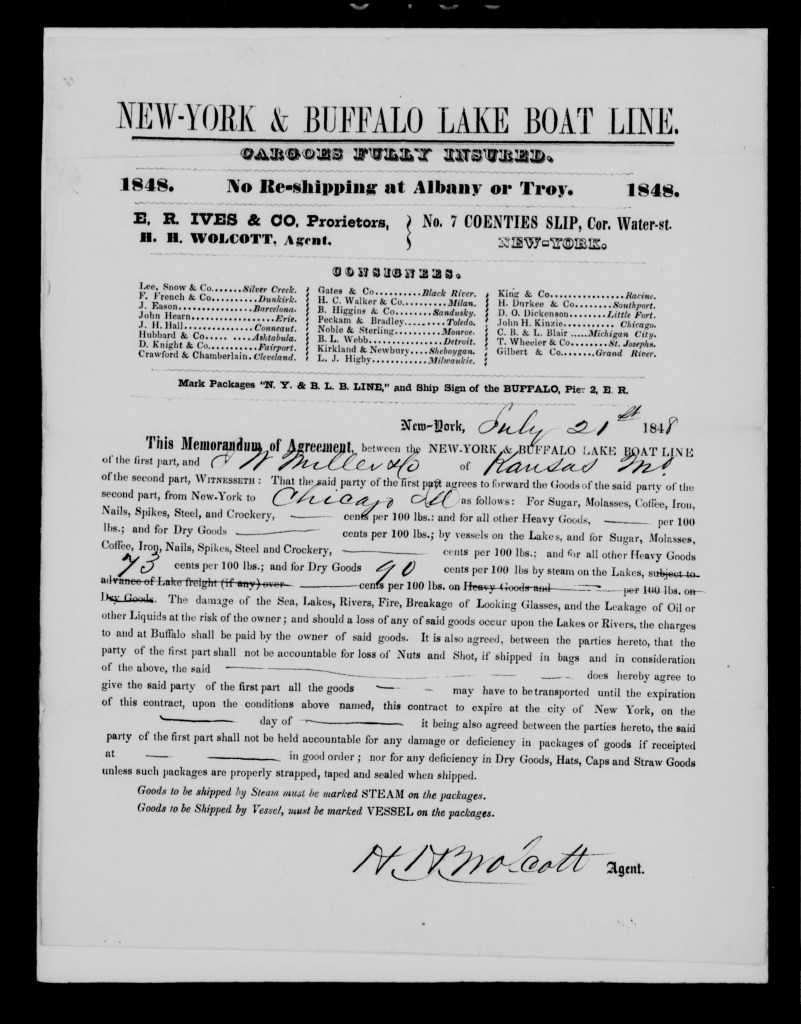

But first—shopping! Drawing cash from the Phoenix Bank in New York City, John Miller spent a week in lower Manhattan (today’s Financial District), purchasing merchandise to the tune of about $3,500. He sent their stock by way of Chicago to St. Louis and finally to their new store near the Miami village. James Aveline, another Indian trader (and sometime-husband of Miami women), said the goods “were well selected and well adapted to the Indian trade, and embraced many fancy and valuable goods.”

Shopping for Myaamia Customers

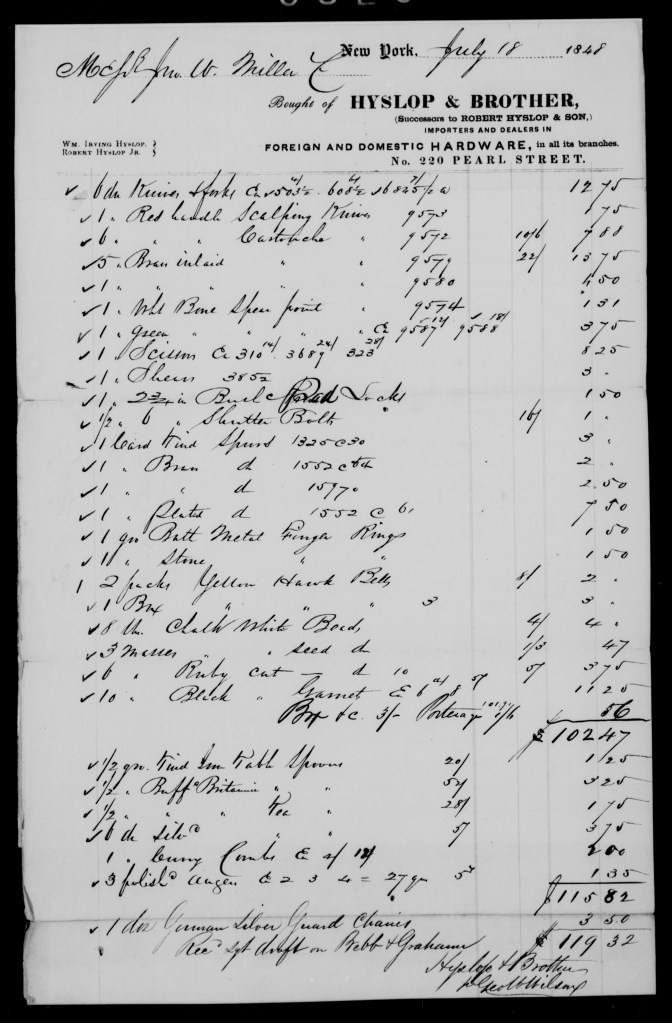

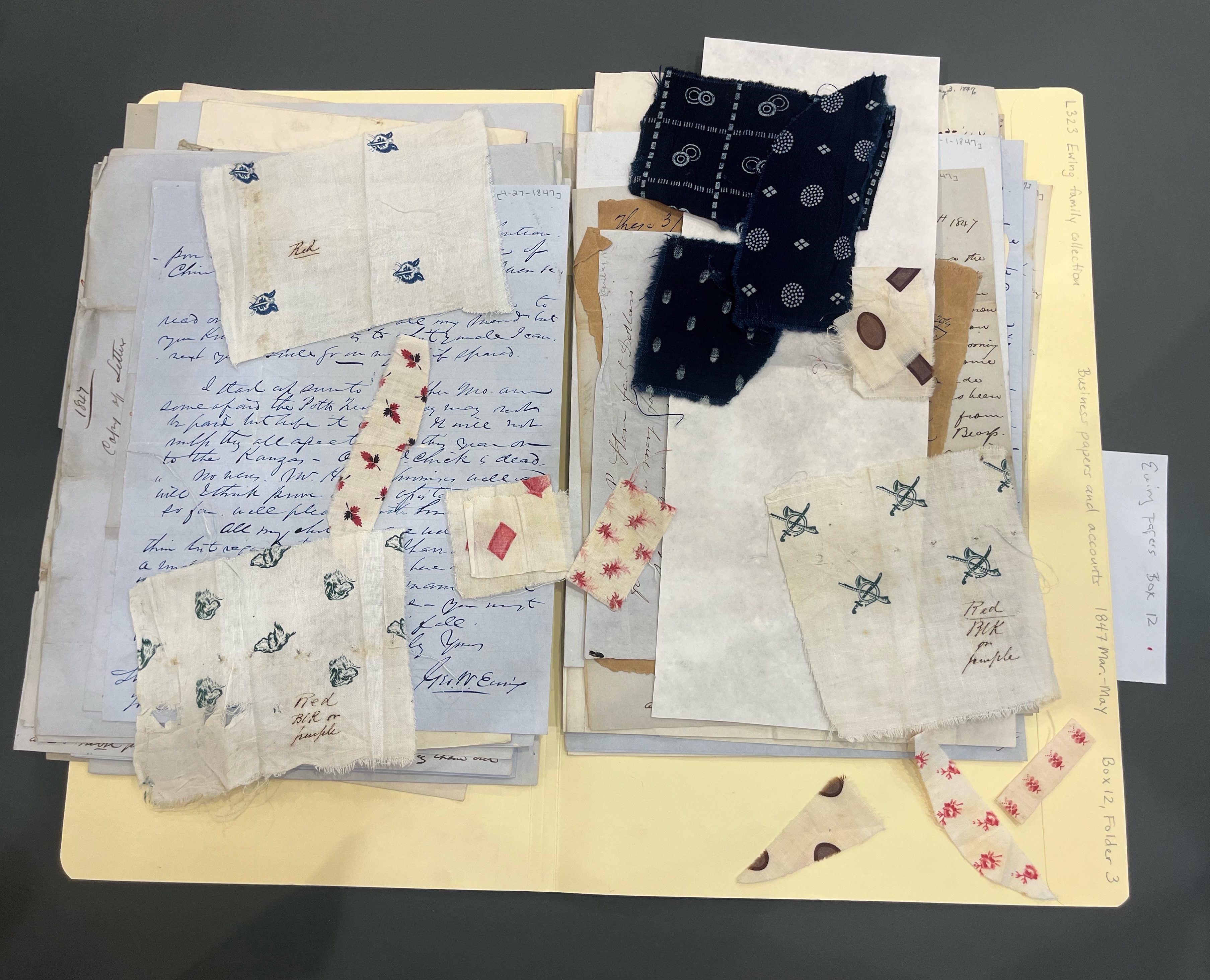

Investigative depositions reveal the items that Miller & Co. purchased in 1848. These included “a lot of fancy ribbons adapted to the Miami tribe,” “fancy Italian black silk,” and four-point blankets. (“Points” are lines woven into blankets indicating their size, easily seen when folded. Four-point blankets were large.) Black cloth seemed popular. Crepe shawls were an important part of their inventory. On Pearl Street, Miller bought of H. H. Weed & Co a dozen “fine Ivory combs,” one gross of “agate” (volcanic rock) shirt buttons, pea coats, “French Twist” coats, gilt vests, mouth harps, both single and double harmonicas, toy bells, “Hooks & Eyes on cards,” half a dozen “Fancy Looking Glasses,” “Rose Hair oil,” and dozens of other items.

Of Benjamin Babcock, John Miller bought six expensive “India Compy. Bandannas” at $5.50 each. On William Street, Miller went on a spree at the fabric supplier Grant & Barton, purchasing many colors in myriad patterns: silks, cottons, and chintz; handkerchiefs, cravats, bandanas, shawls, mackinaw blankets and pants; wool socks for men; hose in child size; assorted taffeta ribbons. He found more prints at Woodbury, Avery & Co. down the street. Here, Miller bought thirteen variations of madder prints, plus shirting titled Naumkeag black, Brick, Mohawk, Red Flannel, Red Padding, Canvas, Mariner’s Stripes, Caroline, and Domestic Gingham. Miller & Co. bought footwear, nearly 200 pairs: boy’s brogans, men’s lace boots, “Youths thick Boots,” and “shoe strings.” Many were “kip” leather made from a younger animal’s hide. After visiting a hat shop, Miller walked next door, where he purchased black embossed cashmere, crepe shawls, and scarves. The same day, he purchased knives, thimbles, tape measures, locks, and ink stands at a hardware store. On and on he went, from shop to shop on Pearl, William, and Beaver Streets. More fancy silks, ribbons, and crepe shawls, bundled and sent in leather trunks to western Missouri.

John Crooks received the merchandise and sold locally to Miami customers through his new mercantile. (At the time, Miller & Co. was one of three such stores operating there.) From the autumn of 1848 to spring of 1849, Crooks profited $2,278.33 (around $70,000 in 2014) in his few months of operation.4 He gauged it a decent success. Crooks wrote to his partner Miller: “I sold goods generally at a good profit but some few things I sold very low. But when I sell on a credit I will stick it to them to make that up. I think trade will be pretty good this winter.” Merchants expected, at that time and place, to make from 45-100 percent profit over New York wholesale prices. (Miller supposed that his partner Crooks sold at 100 percent profit.) Expecting increased markups when the Miami annuities were distributed, Crooks had “reserved for the spring payment one trunk and one bale of fancy goods.”

But Crooks didn’t survive that long. Something happened, and Crooks was dead, sans-pantaloons.

Local attention quickly turned to “a Miami woman with whom he Crooks lived as a wife, and to whom he was married the day before his death by Father Frino a Catholic Priest.”

John Crooks had a new wife. This was a twist!

May 3, 1849

Around 2:30 in the morning, Waapaakihkwa5 told Nicholas Gouin, John Crook’s clerk, that her husband was missing. Gouin then “roused the neighbors” and they searched until daybreak. Gouin–who Waapaakihkwa probably called Šiihšiipa–had Miami heritage himself. With Waapaakihkwa, he had been closest to Crooks. Gouin/Šiihšiipa had keys to the store, and it was his habit to leave them at Crooks’ house, which also happened to be Waapaakihkwa’s house on May 3, 1849.

(You can view a dramatis personae near the bottom of this post.)

There is actually a record (not in “File 57”) recorded on May 2, of the marriage between “Joaneum Crooth” and “Waw-paw-ke-ke-quah,” witnessed by James Aveline and “Goin” (almost certainly Nicholas Gouin), and recorded by Fr. Paul Mary Ponziglione. Crooks had to be baptized before the marriage, although apparently Waapaakihkwa did not.

This record corroborates witness timelines: Waapaakihkwa and Crooks were married on May 2; Waapaakihkwa told Gouin that her husband was missing hours later in the middle of the night; Crooks’ body was found in the creek in the morning of May 3.

In his affidavit, Nicholas Gouin ‘Šiihšiipa’ said that his now-dead boss had been sick for a bit more than a week. Crooks “was deranged for two days before his death, was considered dangerously ill.”

When neighbors found Crooks at dawn, he was in a “small Branch of water–quite dead–on his side.” James Aveline was there, and “saw his dead body lying in a little creek near by—several hundred yards from his trading house.”

Nobody examined his body for marks of violence, they told the investigator. Soon, John Crooks was in the ground, buried.

Investigation

Witnesses vouched for the character of John Crooks. Associates who knew him called him “a sober, prudent & intelligent young man.” The treaty-provided blacksmith said “that he was a man worthy of confidence” who “kept his books correctly.”

His partner, John Miller, called him “a young unmarried man of about 25 years of age, of good habits and character.” He was also sure to say that Crooks was “not given to habits of despondency and gloom.” Perhaps Miller was countering any assumption that Crooks had taken his own life, given that Gouin had called Crooks “deranged” in the days before his demise.

Two things stood out as suspicious, and they pointed directly at Crooks’ new bride.

First, when Crooks’ associates went to search for him, Waapaakihkwa searched in the opposite direction of everyone else, and as it turned out, in the opposite direction of Crooks’ body at the creek.

Second, Waapaakihkwa ended up with the trunk and bale of fancy goods that Crooks was waiting to sell at an increased markup after the spring annuity payment.

Fancy and Valuable Goods

Following Crooks’ death, Gouin, his store clerk, asked Robert Wilson, James Aveline, Michael Richardville, and John Roubidoux ‘Eecipoonkwia’ to help him take inventory of the stock. Nothing was missing, he asserted. Just the trunk and bale of fancy goods that Crooks had in the house.

“After the death of Crooks,” Gouin said, “he saw no more of the goods left in the house except some blankets, & a box of ribbons.”

After her husband’s death, Waapaakihkwa kept the house itself (as well as a horse) as her own property. Later, William Honeywell bought crepe shawls and other items from her at her house “in the Miami Village.” He remembered the “fine black silk goods which she took from a trunk in her possession.”

Crooks’ surviving business partner, John Miller, showed up several weeks later. Traveling from Peru, Indiana, he demanded the remaining goods be given to him. Waapaakihkwa had other ideas.

As James Aveline put it in his statement, “to this demand, she would not listen.” She had stashed the trunk and bale, along with some silver money, at the dwelling of Michael Richardville, another merchant in the neighborhood. (Technically, the affidavit asserted that Waapaakihkwa “took them to the dwelling house of Mr. Richardville & left them with his wife,” probably Margaret Roubidoux ‘Akoohsia,’ a Myaamiihkwia.)

When Miller arrived, Michael Richardville “disavowed any claim or interest in them, and refused to shelter them for the sq**w.” So, the same day Miller appeared, Waapaakihkwa, Mahkateeciinkwia (a leader also known as ‘Little Doctor’) and another unnamed Myaamia person living with Mahkateeciinkwia quickly moved the trunk and bale to Mahkateeciinkwia’s house, apparently on the Miami Reservation.

The “Special Files”

The case notes are held by the U.S. National Archives (in a section of Office of Indian Affairs records titillatingly dubbed “special files”) because John Miller applied for federal intervention. According to the 1834 “Act to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian tribes, and to preserve peace on the frontiers,” U.S. law required merchants to hold a license from the (federal) Indian office. This was a longstanding law, going back to the eighteenth century. Miller argued that Miller and Co. had filed a bond and had verbal license to sell in the Indian Country. He claimed that Crooks had $800 cash, and goods purchased at $1009.24. Supposing those goods to be sold at 100 per cent profit (double the price paid to New York wholesalers), he claimed that the Miami Tribe owed him $2,818.48 plus interest.

Yet the investigating federal clerk argued that “the Miamis, as a tribe, are not implicated in the stealing of these Goods.” Indeed, Waapaakihkwa cohabited with Crooks as his wife, was married by a priest, “and who, as his widow, and therefore interested in his estate, would not, perhaps, have been doing greatly wrong, to take care of the Goods, according to her discretion.”

In other words, if Miller was only interested in retrieving property, he was out of luck. “The murder is of little moment,” the investigator penned, “the Robbery or Stealing is the matter to be proven.”

“The [investigations’] papers do not establish the fact, in such a way as to make the loss of any [goods] chargeable upon the funds of the Miamis as a tribe. Beside [sic] it is conceded that the parties claiming had no regular license.”

Unanswered Questions

The case files end there, but the episode opens new questions for me as a historian.

First: Who was this Waapaakihkwa? This is difficult to answer. There are several Myaamia women attested in the historical record, probably six in all from this era. None fit perfectly.

An additional oddity is that James Aveline (who knew this Waapaakihkwa since she was a child, he said) said Waapaakihkwa left Indiana in 1848, and not the year of removal, 1846. Perhaps this was a miswritten date.

Second: What were Myaamiaki doing with these items? Up to now, I’ve been under the impression that the effects of removal caused steep declines in Myaamia-specific artistic expression in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, particularly among those Myaamiaki who relocated to Kansas and then Oklahoma. But quantities of earbobs, silks, shawls, ribbons, threads? We can connect the dots.

Third: Who was involved in Waapaakihkwa’s social world? This is an unusually intimate archive. It certainly reveals more about Crooks’s network than Waapaakihkwa’s. A brief overview of characters that made statements to investigators provides us a glimpse into the small merchant community (dramatis personae):

Myaamiihkwia. Married John Crooks, local shop-owner, the day before Crooks’ death. As his widow, she then moved some store stock onto the Reservation.

local merchant, partner in the firm Miller & Co. Died. May 3, 1849.

Peru-based merchant who made the shopping trip to New York. Initiated the investigation to pursue compensation after his partner, Crooks, died.

John Crooks’s store clerk, and the first person Waapaakihkwa notified of Crooks’ disappearance on their wedding night. Gouin would soon be allotted along with several of his children.

merchant who witnessed the inventory of Crooks’ stock. After Crooks’ death, his clerk (Aveline) would not allow Waapaakihkwa to store the trunk and bale of goods at his store, but Richardville did allow her to stash the goods at his house. I believe this is Michael J. D. Richardville (b. 1800), one-time spouse of Marie M. Roubidoux (Miami) who was an aunt of John Roubidoux ‘Eecipoonkwia.’

Michael Richardville’s store clerk, who provided context for the business of Miller & Co. Of Waapaakihkwa, he stated “I have known this Indian woman, of whom I have spoken so often above, since she was a child.” While there are more than one Myaamia James Aveline, I think this is the (non-Miami) James Aveline who married Catherine Godfroy (Miami) and Alaamhkihkamohkwa (Miami) in Miami County, Indiana. His deposition was taken in Miami County, Indiana.

probably a very young man in 1849. Called to witness the inventory of Crooks’ stock. Future chief of the Miami Nation.

a “resident of the Indian Territory.” After Crooks’ death, bought shawls and other items “not recollected” from Waapaakihkwa out of a trunk at her house. Honeywell was at one time (perhaps in 1849) married to Sarah Owl ‘Lenipinšihkwa,’ his Miami-Delaware spouse.

blacksmith paid by U.S. to serve Miami needs, as per treaty. Witness with no clear familial ties to Myaamiaki. He claimed that Crooks “was a man worthy of confidence” and “he kept his books correctly.”

witness with no clear familial ties to Myaamiaki. After Crooks’ death, he observed Waapaakihkwa with “a sack of specie little larger than a shot bag.”

also known as “Little Doctor,” he (and another unnamed “Indian”) helped Waapaakihkwa move the bale and trunk to his house, thwarting John Miller’s attempt to retrieve them. He was one of the five Miami delegates to sign the 1854 Treaty of Washington. Not interviewed by investigators.

not a witness, but mentioned as a Miami person who took a letter and cash from Crooks (before his death, “Miami Nation,” Kansas) to Miller (Peru, Indiana), in November of 1848.

Thoughts

The investigation feels odd because although Waapaakihkwa is clearly a “person of interest,” the investigation is not primarily interested in how Crooks perished, but in compensating John Miller for his inventory. However, this is revealing in itself. In the context of the Myaamia economy at this time, merchant firms routinely applied for and received recompense from the Miami Tribe’s national fund. In the 1820s-1840s, there were hundreds of firms like Miller & Co. Crooks put it in ink: “when I sell on a credit I will stick it to them.” Miami debts were paid out of the Miami national annuities. This system siphoned off Myaamia wealth to those firms who could “prove” they were owed money by Myaamiaki. Embezzlement and fraud followed.

Another plot that never developed was the question of jurisdiction. In our world (particularly post-McGirt, or for that matter, post-1885 Major Crimes Act), we are primed to think through the prisms of trust land and status for crimes involving American Indians. But where the death occurred (apparently not on the Miami Reservation but rather in the state of Missouri), and the status of the principals (a non-citizen American Indian woman and a U.S. male citizen) was never broached as a legal issue.

File 57 reveals a continuation of life–in all its messiness–after the Miami Nation’s 1846 removal. All of the characters had come from Indiana (except, perhaps, the priest who married Crooks and Waapaakihkwa). Moreover, the archive suggests the extension of the fabric fashions of the Myaamia community to the Kansas reservation after removal.

File 57 tells us this: In 1849, John Crooks accrued Myaamia debts through his mercantile. The day after he married Waapaakihkwa, he lay dead by the creekside without his pants on. The investigation–and therefore most of the information we have about this incident–consists of lists of trade items stocked for sale to the Miami community.

- Unless otherwise indicated, primary source information is taken from RG 75, Special Files 1840-1804, Special File 57, M574 roll 6, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ↩︎

- John W. Crooks appears not to be closely related (if at all) to the more well-known trader, Ramsay Crooks. ↩︎

- It is unclear how, or whether, John W. Miller was related to the Ewing & Ewing associate James T. Miller of Peru. ↩︎

- Using Robert Sahr’s historical conversation data, converting 1849 to 2014’s inflation conversion factor. ↩︎

- In this blog post, I am spelling the subject Myaamiihkwia’s name as Waapaakihkwa. In the record, it is commonly spelled (with little variation) as Waw paw ke ke quah, Wah-pah-ke-ke-quah, Wa-pa-ke-ke-qua, or other very similar versions. Note that this is not the same as the more common Myaamia name Waapaankihkwa. There were several Miami women (no men that I am aware of with the male version of the name) called Waapaakihkwa in the nineteenth century. Thanks to Daryl Baldwin, David Costa, Hunter Thompson Lockwood for their help. ↩︎

Leave a comment