What kinds of clothing did Myaamia (Miami Indian) people wear prior to contact with Europeans?

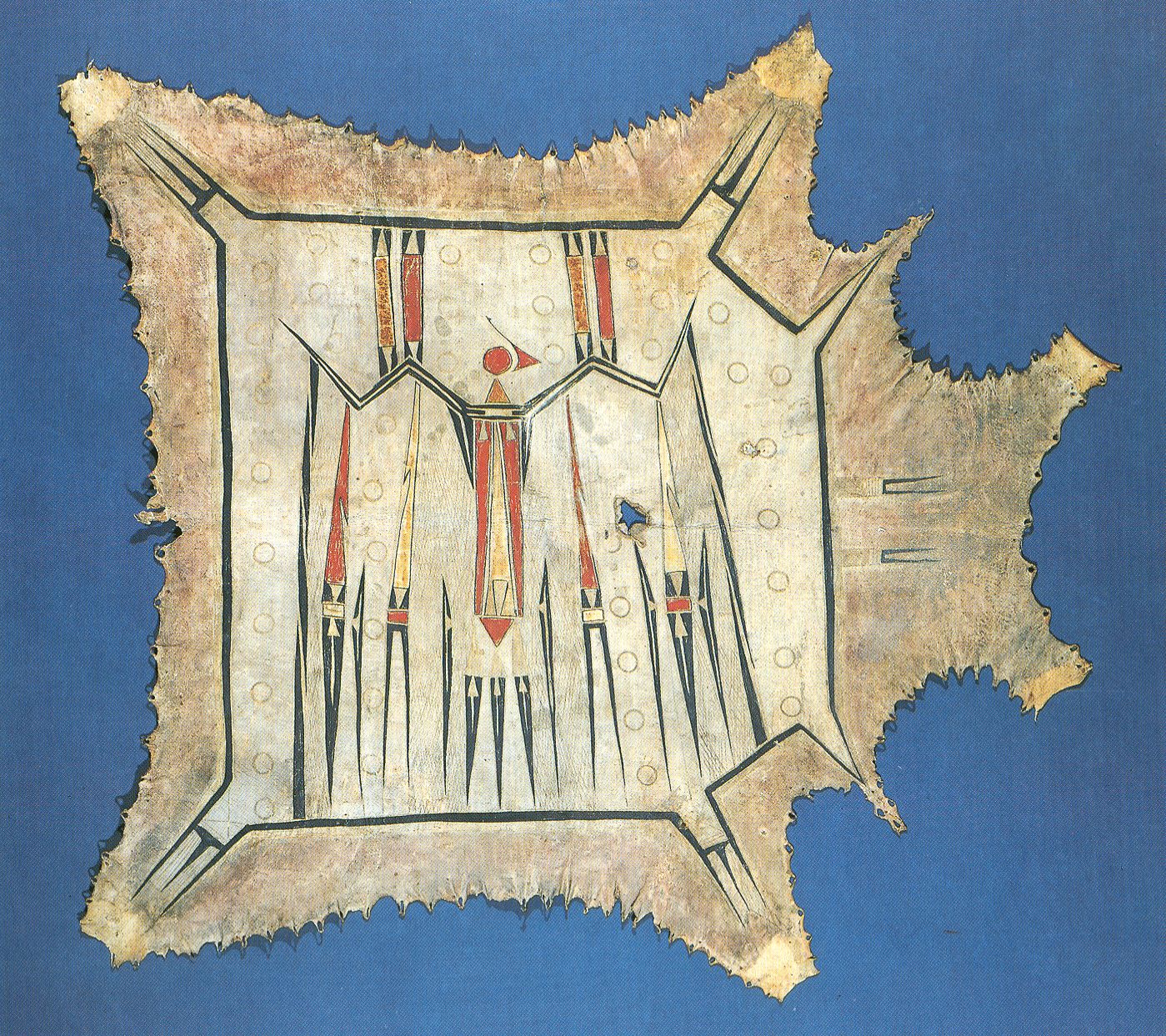

In the period of time prior to contact with Europeans, Myaamia people wore clothing made from hides: leggings, breechcloth, moccasins, skirts, shirts, and added large blanket robes during colder weather.[1] The bison robes held by the Musée de l’Homme in Paris are one of the finest examples of painted winter robes (see image below).[2] In addition to bison hide, Myaamia people utilized beaver, elk, mountain lion, wildcat, wolf, otter, and most commonly of all: white-tailed deer. During the summer months, Myaamia people wore as little clothing as necessary. There are many early European accounts of Myaamia men wearing only a breechcloth and moccasins during hot weather. Some early accounts describe Myaamia men as naked during warmer weather, but this was probably an exaggeration as the breechcloth left all of the upper body and most of the legs exposed. Myaamia women usually wore knee length leggings, wrap skirts, and tunic-like shirts, even in the summer.[3]

Some of these early clothing items were decorated with paint and or porcupine quill work. Decorated clothing items were usually worn during special events: feasts, celebrations, important negotiations, etc. During the pre-contact period, Myaamia decorative designs and materials probably underwent many changes. As the Myaamia encountered new people and new materials, it is quite likely that they would have adopted and altered the designs and materials of other groups.

Both of these designs figure prominently in clothing produced in the 1800s and continue to be produced by Myaamia people today. The diamonds occur most prominently in silk ribbonwork and the hourglass shapes in hairbows worn by Myaamia women.

Other than the trade shirt wrapped around his midsection, this is how most Myaamia men would have dressed in warmer weather during the pre-contact period.[4] Tattooing was common the Myaamia as well as the Meskwaki, but Myaamia designs probably would have differed slightly from the Meskwaki designs seen here.

[1] Raymond E. Hauser, An Ethnohistory of the Illinois Indian Tribe, 1673-1832 (Phd diss., Northern Illinois University, 1978), 130-32 and especially note #17 on 132. Bert Anson, The Miami Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970), 20. Josephine Paterek, Encyclopedia of American Indian Costume (Denver: ABC-CLIO, 1994), 60-62.

[2] George P. Horse Capture and Ann Vitart, Robes of Splendor: Native American Painted Buffalo Hides (New York: New Press, 1993) 51-52, 119, 121.

[3] Anson, Miami Indians, 20; Paterek, American Indian Costume, 60-62; Harvey Lewis Carter, The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 12. Carter suggests that the “naked” terms may be the result of the early Myaamia lack of trade cloth, with which other neighboring tribes “covered” themselves. For an image that approximates the dress of Myaamia men pre-contact see Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 157. Sabrevois states that while Myaamia men wore very little, Myaamia women “covered themselves.” See Jacques Charles Sabrevois de Bleury “Memoir on the Savages of Canada as Far as the Mississippi River, Describing Their Customs and Trade” in Rueben Gold Thwaites, ed., Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin vol. 16 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1902), 376.

[4] Guerrier Renard from Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, EST OF-4 (A). Accessed online at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7822108n. Couplipa was captured by the Myaamia and given as a gift to the French, likely to cover the obligations created by the death of Frenchmen in military efforts that supported Myaamia communities. Brett Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic Slaveries in New France (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 219.

Updated: January 7, 2021

Reblogged this on Kerry Red Atjecoutay.