October 6, 1846 Peru, Indiana

Content Warning: This post discusses specific names of Myaamia people impacted by Removal. It is possible that you may have a personal connection with some of those individuals.

“The first emigrating party of Miamis was started from Iihkipihsinonki ‘Peru, Indiana’ on the 6th October 1846.” So began the “Report of the Acting Contractors for the Emigration of the Miami Indians,” written by Alexis Coquillard and Samuel Edsall. Unrevealed by these simple facts was the heartache, fear, and anxiety of Myaamiaki ‘Miami people’ 175 years ago today.

With great anxiety, those on the five canal boats being carried on the Wabash & Erie Canal must have wondered where they were going, what it would be like, where they would live, what they would eat. Would it be anything like the beloved Myaamionki ‘homeland’ they had always known? Perhaps they were remembering the report of the Myaamia delegation who had visited the new reservation west of the Mihsi-Siipiiwi ‘Mississippi River’ the previous year. They must have despaired to think of leaving their beautiful Myaamionki for land the delegation had described as “a miserable despicable country.”

Many of them had relatives who were not on the canal boats, Myaamiaki who were exempt from Removal or had fled. Families were torn apart. A few on the boats, like Šiipaakana ‘Thomas Godfroy,’ were exempt from Removal but could not bear to see their relatives being forced to leave, and they were concerned for the safety of their loved ones. Yet they too left family behind as the boats began to move eastward on the canal. Everyone who was exempted had family and friends being removed. Their hearts were breaking too, as they tearfully parted from their beloved friends and relatives.

Some anticipated that their relatives would come back from the land west of the Mihsi-Siipiiwi. Removal Agent Joseph Sinclair had consented to allow some members of the families of Mihtekia ‘Coesse,’ Meehkwaahkonanka ‘Benjamin,’ Misihkwa, Šowaapinamwa ‘Antoine Revarre,’ Pinšiwa ‘Wildcat,’ and Mahkateehsipana ‘Cotesipin’ to remain in Indiana, because they owned land and had crops to harvest and cattle, horses, hogs, and other farm animals. Those families agreed to remove at their own expense at a later date. Still, these families must have wondered if they would ever see their husbands and fathers again. Seekaahkweeta, mother of Šiipaakana, demanded that Sinclair promise to see that her son would be safely returned to her.

Myaamiaki on the canal boats were not only leaving the living people that they loved, they were also leaving the land where their ancestors were buried. They had only a few minutes to collect their most valuable possessions in a bag before the soldiers forced them from their homes to the Removal camp in Iihkipihsinonki. Some of them chose to take dirt from their ancestors’ graves. We cannot begin to understand the depth of feeling about leaving their ancestors’ graves behind, knowing that in those few stressful moments, they thought of their ancestors.

For the Americans in the area, the forced Removal was a sight to see, and many of them came to watch or perhaps, in some cases, to say farewell to their neighbors. One of those who came to see their departure was Ellen Cole Fetter, a young child whose older brother, a prominent lawyer in Peru, had represented Mahkoonsihkwa ‘Frances Slocum’ in obtaining her exemption. Many years later, Fetter wrote,

“One picture engraved on memory when I was perhaps about ten years old was the going away from their home so near of all the full blood Miami Indians. Government had bought their land and they were about to depart for new hunting grounds in Indian Territory. A company of blue coated soldiers had come to escort them and they were to depart on the several canal boats awaiting them. I was taken to see them on the eve of departure. We crossed - forded the river in a buggy - and the Indian camp was above and beyond the present cement bridge. There were tents and camp fires over which supper was cooking, and there was weeping among the squaws who were mourning for their dead. They had put in sacks earth from the graves of their kin and tribe to carry with them to the strange country. My heart was made very tender by their weird scene, and has never lost sympathy with the wrongs which were wrought against our friendly predecessors.”

Although Fetter did not accurately report some of the facts, the tragedy of the event she witnessed was clearly imprinted in her memory. Additionally, her description of fording the river to a location that at the time of her writing was on the other side of the “cement bridge,” also known as the Wayne Street bridge, helps us to identify the approximate location of the Removal camp.

Similarly, John Dawson, Fort Wayne newspaperman and later Utah Territorial governor, was present the day of Removal and recalled,

“Well I remember the sober, saddened faces, the profusion of tears, as I saw them hug to their bosoms a little handful of earth which they had gathered from the graves of their dead kindred. But stern fate made them succumb; and, as the canal boat that bore them to the Ohio river loosed her moorings, many a bystander was moved to tears at the evidences of grief he saw before him.”

As mules began to pull the boats along the canal, Myaamiaki on board passed by many familiar places for the last time. The land where they boarded the canal boats had previously been the Francis Godfroy Reserve, land that had belonged to Šiipaakana’s father. A bit further east, they passed through land owned by Waapeehsipana ‘Louis LaFontaine’ who was on one of the boats with them. In what had become the town of Wabash, they went through Keetanka’s (Charley’s) Reserve and the site of Keetanka’s house and passed Paradise Spring, where they had signed the Treaty of 1826, ceding most of their land north of the Waapaahšiiki Siipiiwi ‘Wabash River.’ Periodically, the canal ran along the side of the Waapaahšiiki Siipiiwi, which had provided water, transportation, rich soil for their cornfields, and more for them since time immemorial.

The boats passed by the site of Meehcikilita’s ‘Le Gros’s’ village at present-day Lagro. Many on the boats would have remembered Meehcikilita as a founding member of the National Council. Many more may have remembered the “the immense bowlder [sic], seven or eight feet long and four or five feet wide and perhaps four or five feet high,” at which they always made an offering of tobacco when they passed by. This day it did not matter that they had no tobacco to offer. The boulder had been blown up and removed so it would be out of the way of the building of the canal.

Then, Toohpia and his family passed their own home at Wiipicikionki ‘the Forks of the Wabash.’ Since they were descendants of Pinšiwa ‘JB Richardville,’ they were exempted from Removal. They were on the Removal boats because, as Principal Chief, Toohpia felt a responsibility to go with his people. Next to Toohpia’s home was the council house where the Miami National Council signed several treaties, including the Treaty of 1840, in which they agreed to this Removal.

As they approached what is today the town of Roanoke, they went by the reserves of Waapimaankwa ‘White Loon,’ Neewilenkwanka ‘Big Legs,’ Waapeehsipana ‘Louis LaFontaine,’ and then Waapeehsipana ‘White Raccoon,’ a portion of which later was reserved to Na-ma-quan-ga* ‘William Chappene’ after Waapeehsipana’s death. Waapimaankwa, Neewilenkwanka, Waapeehsipana, and Chappene, as well as the family of Waapeehsipana, were all on the Removal boats.

Near the end of this horrendous day, we see that Myaamiaki were not only fearful and heartsick, but they were also physically sick. They were not used to travel by boat, especially not when they were crowded into such a small space. They could not imagine continuing another day like that, but as we will see in tomorrow’s blog post, they did continue on.

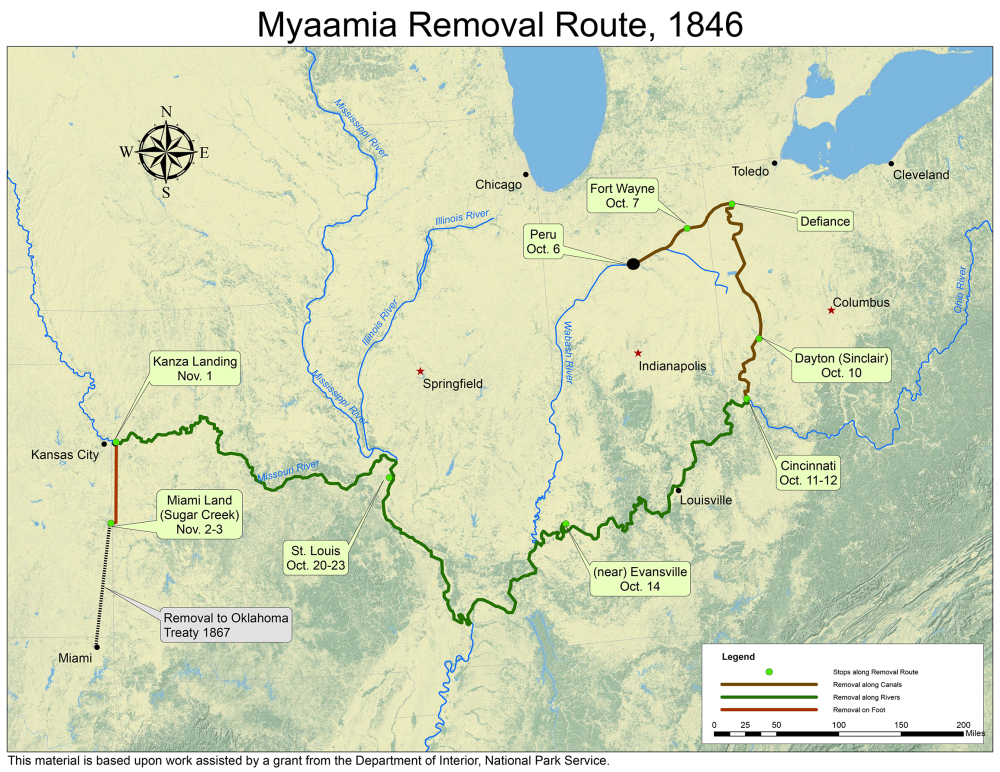

Map by Kristina Fox with annotations by Diane Hunter from George Strack, et al., myaamiaki aancihsaaciki: A Cultural Exploration of the Myaamia Removal Route (Miami, OK: Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, 2011), which was supported by a National Park Service Historic Preservation Grant (#40-09-NA-4047)

* This name was poorly recorded, and as a result, we do not know what it means or how to spell it using the modern spelling system.

Post written by Diane Hunter, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. Diane can be contacted at dhunter@miamination.com.

My name is Tamzen Godfroy. I am a descendent of Chief Godfroy and still reside here in Peru, Indiana.

Thank you so very much for keeping our history alive!!

God’s Blessings to you!

Tamzen Godfroy