November 5, 1846 Arrival at the Miami Reservation

Content Warning: This post discusses the conditions upon arrival at the Miami Reservation and death of Myaamiaki on the journey.

In the November 4 blog post, we saw that some Myaamiaki had arrived at the Miami Reservation on Sugar Creek in the Osage River Sub-Agency.

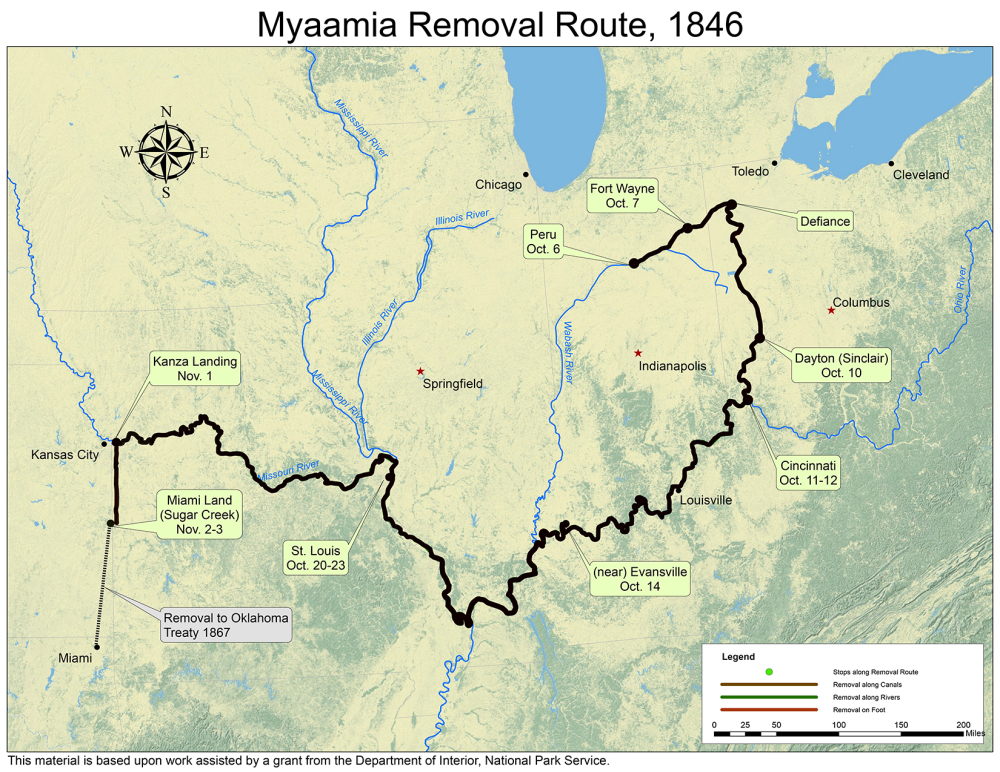

Map by Kristina Fox with annotations by Diane Hunter from George Strack, et al., myaamiaki aancihsaaciki: A Cultural Exploration of the Myaamia Removal Route (Miami, OK: Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, 2011), which was supported by a National Park Service Historic Preservation Grant (#40-09-NA-4047)

Upon arrival, Removal Agent Joseph Sinclair turned “over the Miamis to Col [Alfred] Vaughn Sub Agent” of the Osage River Sub-Agency. Reports varied regarding Sinclair’s performance during Removal, but it is quite clear that we were not happy about his lack of attention to Myaamia concerns.

Sub-Agent Vaughn immediately made a list of Myaamiaki “delivered … into [his] charge.” He counted a total Myaamia population of 42 heads of families with 91 males over 18; 51 males under 18; 128 females over 18; and 53 females under 18; with a total population of 323. Vaughn’s count of Myaamiaki was eight people more than Sinclair had counted as boarding in Iihkipihsinonki ‘Peru, Indiana,’ even considering seven deaths and two births on the journey. His explanation was not that he miscounted but that “it appears that thirteen Indians had got on board the Canal Boats at Peru without my knowledge; this might easily occur in the night during the time they were being put on board.” Through his own statements, Sinclair provided many opportunities to see that he was negligent in his duty.

As Myaamiaki entered this new land, their thoughts turned toward the land they had left. In a letter to U.S. President James K. Polk, the Miami National Council wrote, “If we have not fulfilled our promises in due time, and if against your best wishes, you have been compelled to send troops to force us to compliance, you will easily account for it, Great father, in consulting your own feelings about the land of your own birth.” Regarding this new reservation, they noted to Agent Vaughn that “their new country had been represented to them as a miserable, barren section without wood, without water, in fact in the open prairie where no one could exist, and where those who did emigrate would find a speedy grave.” Both Sub-Agent Vaughn and trader George Ewing reported that after seeing the reservation, Toohpia commented that it was much better than they were expecting. They were expecting “a miserable despicable country,” based on the reports of the delegation who came to see the land in August 1845.

Map by E.B. Whitman and A.D. Searl, General Land Agents, Lawrence, Kansas. Image courtesy of KansasMemory.org, Kanas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply.

Though better than expected, the conditions were not good for Myaamiaki. The weather was unusually cold for early November. In a letter to U.S. President James K. Polk, the Miami National Council wrote, “we have pitched our tents,” and “our feet have trodden the withered grass of the widespread prairies of the Mississippi and without a shelter we will have to face the rigors of the fast approaching winter.” Despite the long years of the United States pressing Myaamiaki to go west, they never made provisions for housing when they arrived. Myaamiaki had only tents to live in, but they began building houses. They had built 19 houses by December, but it was spring before they had enough houses for 42 families. In a letter written upon arrival at the Westport Landing, Toohpia ‘Francis LaFontaine’ remarked that two-thirds of Myaamiaki had been sick during the journey. Keeping sick people in tents in bitter cold inevitably ends in deaths. From the time Myaamiaki left Iihkipihsinonki, Indiana on October 6 until the end of 1846, at least 30 Myaamiaki died. Unfortunately, we cannot identify most of those who died by name.

Other than Ottawa, the elder who was buried on Bloody Island, the only name we have is Šiipaakana ‘Thomas Godfroy,’ a 16-year-old boy. As a son of Palaanswa’ Francois/Francis Godfroy,’ Thomas was exempt from Removal, and yet he was on the Removal boats. To speculate about why he was on Removal, we must understand Myaamia kinship. In a Myaamia family, the children of one’s father’s brother and one’s mother’s sister are not cousins, but siblings. Šiipaakana’s brothers and sisters who were not lineal descendants of Palaanswa and unrelated people who lived in their household were not exempted and had to be removed. Perhaps Šiipaakana could not bear to see his loved ones leave. Perhaps he felt a need to ensure that they would arrive safely at their destination. Waapimaankwa ’Thomas F. Richardville’ later testified that Šiipaakana chose to be on removal “to see how their friends were to be situated.” Joseph Sinclair, the Removal Agent, would not have had any objections to taking one more Myaamia person west of the Mississippi River. In any case, Šiipaakana was on the Removal boats to the Miami Reservation on Sugar Creek. We first hear about Šiipaakana in a December 24, 1846 letter from Toohpia. He wrote, “Thomas Godfroy is very sick, his recovery is doubtful.” In a December 31, 1847 letter, we read the response to this news from Seekaahkweeta, Palaanswa’s widow and Šiipaakana’s mother.

“I drop you these few lines by my son William to inform you of my present distress. I have [received] news from the West that my dear son Thomas was about to die and that there is no hopes in his recovery, which I do assure you is a pang to my heart,…& what I feel so bad is that he died without my seeing him. I blame Mr [Sinclair (the Removal agent)] for he promised if I would let [Šiipaakana] go that he would see that he would come back when he did. It was under that promise that I consented to let him go, but [God’s] will be done. I relied on him as a white man of honour and Father to us, but he belied me.”

We can well imagine that Seekaahkweeta expressed the feelings of all the mothers whose children died during this most tragic time. Šiipaakana’s death weighed heavily upon his family. In fact, his younger brother Waapanaakikaapwa ‘Gabriel Godfroy’ named his first child, Thomas, after his lost brother.

Those who remained mourned the departure of their friends and family, while Toohpia expressed the mourning of those on Removal,

“Dear to us was that home of our children, still dearer to us were the ashes of our forefathers, and how could we expect to find anywhere else aught that would compensate for such a loss.”

While mourning the loss of their friends, family, and their beloved homeland, Toohpia and other Myaamia leaders were already planning their future as a sovereign nation. In their letter to President Polk, Myaamia leaders asked for the funds to start a Myaamia school on their reservation, “at the hands of the Catholic priests who reside from the present amongst our friends the Potowatomies of Sugar Creek, we hear them praised by all acquainted with them.” Many of those Potawatomi had once lived among them along the Waapaahšiki Siipiiwi ‘Wabash River’ before their Trail of Death in 1838, and Myaamia leaders trusted them. In requesting the funds for the school, they exerted their status as a sovereign nation by emphasizing that they would run the school, not the United States. Since time immemorial, Myaamia elders, leaders, and educators had looked after the welfare of the next generation, and they intended to continue to do so in their new homes.

Now that we have completed the Removal journey with Myaamiaki, we will return to monthly blog posts. In the next installment on December 3, we will see that Removal-related events continue to occur.

Post written by Diane Hunter, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. Diane can be contacted at dhunter@miamination.com.

Every time I read about my ancestors, I can not believe how horrible people can be. My heart cries for the past, present and future of our families.

I’ve read every word, and my heart aches. Thank you for posting this journey of our ancestors.